by Zachary Clemente

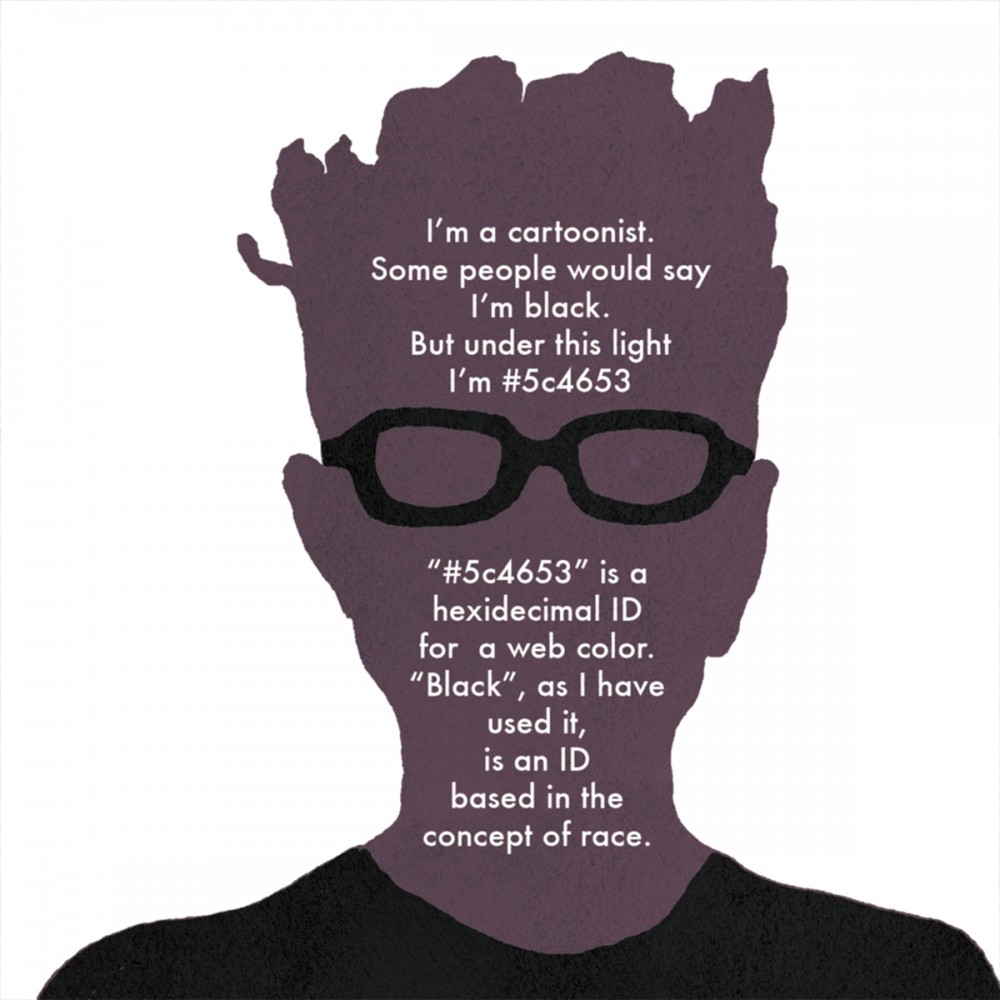

As the Sunday of SPX got started, I had the opportunity to sit down with Ron Wimberly over “breakfast” in the mostly vacant hotel restaurant to discuss his work past, present, and future, what it means to foster community, and how we can adjust the Dream. Wimberly is known for Prince of Cats, She-Hulk, as well as Lighten Up at The Nib. As a note, this is more of a conversation, so expect depth and breadth, not release dates. Additionally, all art is either Wimberly’s or of Wimberly himself.

Comics Beat: When I look at your catalog of work and how people talk about your work, it’s surprising to see you have a relatively smaller or perhaps more curated portfolio of published work than expected. Is that something you aim to change or is that how you work?

Ron Wimberly: I have a very full schedule, so I don’t want to change the level of curation. I don’t want to do things to do things, but the next two, three years, I have a full schedule. I wanna get things out – it’s more about I wanna get ideas out. I’m one guy, it’s not like Marvel where it’s almost like a real estate game – get as many books [out] and control the shelf space in a comic book store. That’s not my interest, but I do want to put out more work. I spent a lot of time in the lab thinking about things. I think I was pretty careful […] I wanted to put myself out. I was offered work but when it came down to it, instead of do a job where I make a little bit of money doing comics, I’d rather do some ad work or illustration or something to pay my bills, you know? As opposed to “lemme do a comic that I really don’t want to do” that takes five times as much work to make half as much money. I write my stories, I research, and I draw on my own and now that I have the opportunity with Image and some other opportunities, I’m ready to get out a lot of the work that I’ve been in the lab [working] on.

CB: Trying to focus your passions?

RW: Yeah, I can’t help it. I’m weird, maybe spoiled to a self-destructive level. I think I’ve done things that I didn’t love and I hope that they’re not complete garbage, but it’s difficult for me. I try to make it so that I’m really liking what I’m doing. I try.

CB: When you look back on your work for Marvel on She-Hulk, how do you feel about that?

RW: At first they approached me to work on that job and I’m not sure that Charles [Soule] was even attached yet. They hit me up and I talked to the editor at the time saying “yo, this sounds really cool and I’d be really into it and I’d do it if a woman writes it,” then I didn’t actually hear from them again, and then Charles did it.

I did a panel with Kelly Sue [DeConnick], which is when I met her and whole bunch of other great folks. I remember seeing Kelly Sue’s Carol Corps there and I mentioned that they had asked me do something and I wasn’t going to do it, but I saw how excited they were for She-Hulk and I thought “now I wanna do this.” It was ’cause I really liked her fans; they were organizing and doing all types of stuff together and I was thinking “wow, that is the draw to working for Marvel.” The possibility of all types of cool people to view the work – that’s what I wanted.

CB: Use that real estate space for good.

RW: I wanted that platform, yeah.

CB: Do you feel like that platform has helped people who viewed your Marvel work move into the work for you?

RW: Yeah, maybe. That’s what’s worked for Kelly Sue too, you know? […] Absolutely, but I’m not as professional as Kelly Sue is and I’m trying my best. She’s my model, even though we’re a little different ’cause I’m a cartoonist and she’s a writer. She’s like my role model in comics. When I first started in comics, Paul Pope was my dream; I saw what he was doing…he was like a comic book rockstar. Now I feel like Kelly Sue is my dream ’cause she’s saying things to people who are listening, it looks like she’s created a community. […] Where I am right now, at my age, community is very important to me. So in my neighborhood, you get to a point where it doesn’t really matter what you’re doing, sure you wanna do something that you love, but you really want to do around people that you care about, know what I mean?

You could be digging a ditch with your best buddies, like moving trash, and it’s something different. You could have the best career, doing everything you dreamed of doing with a bunch of douchebags and it sucks.

CB: Are the feelings of community, in some ways, where Sunset Park is coming from?

RW: Yeah, absolutely. Everything I’m doing is dealing with this. You know, I have a one-track mind. All of my ideas spring forth from whatever existential things I’m dealing with, so in New York right now, in my life, it’s “Where do I live?”, “Where do these people live?”, “How is this neighborhood changing?”, “Where did that store go?”, “Where did those people go?” So all that’s in Sunset Park and I’m working on another project called GratNin, short for Gratuitous Ninja and it’s about that too. The older I get, the most I see how history has informed where I am now and my community and my identity – these are things that are really important to me. So of course that’s what the work’s gonna be about.

I see a lot of comics and yeah, they’re about the real things that these people are thinking about, for better or worse – and that’s what I’m thinking about all the time so you know, I gotta put it in a comic or what’s the point?

CB: Has it been this time for introspection that’s halted the creation of this work? Have you needed to collect and consider all this stuff first?

RW: I’ve been thinking about it the whole time and I’ve been wanting to push the work out, I’ve just haven’t been able to sell it. I was really fortunate for Kelly Sue, Brandon [Graham], and then Joe [Keatinge] all saying I should come to Image to do it there. I think I wasn’t ambitious enough to do it on my own, like the scale – but I should’ve been. I did a GratNin about the ninja character being tracked down by a corporation that collects student loans and that was about what I was going through at the time and that was online for free.

It’s weird man, one of the great things about SPX is I’m seeing all these kids who’re doing it, you know? They’re braver than I am – they’re doing it without a net. I mean, maybe they have a safety net, maybe they have their job or whatever, but it’s like the gall for me to expect that doing these weird works would actually pay my bills is wild. Maybe that’s why you haven’t seen as much work. Now I have the opportunity to say these things and to have it pay my bills while I do it, so I think they require the amount of attention that I say I can’t […] but I do think that people do manage to do both; support themselves with some other shit then get out their opus. Yo, if they hear or read this, keep with the struggle.

CB: It reminds me that Kelly Sue used to be a manga translator before being published as a comics writer. She did Slam Dunk!

RW: Yeah, that shit is dope.

CB: It might be that transition of works that’s the hardest.

RW: I’m sure she was writing before that but it’s kind of like how I’d go to the museum to paint to paint the masters, you know? Of course that guy’s [Takehiko Inoue] a fucking master.

CB: Who are your masters in that creative sense?

RW: Emory Douglas, Tadanori Yokoo. Storytelling-wise, if I think about the people I’m looking at right now and they’re still alive, I always think about Jason. I’m thinking a lot about Daisuke Igarashi – he’s ill. I’ve been looking at his timing, his storytelling. Your dude who did Pluto?

CB: Naoki Urasawa?

RW: Yeah, Urasawa. Big influences…yo, right now I’ve been watching Paul [Pope] go through a stage of really getting back in the gym with his work and that’s inspiring to me on a personal level. Yo, you don’t stop growing and I watched this dude, in terms in perseverance and getting through life and continuing to make work, he’s a new type of inspiration to me now.

CB: Especially with someone like Paul Pope, it’s so easy to view him as a fixture instead of someone who will grow and evolve.

RW: That’s what I think is good about it, ’cause we’re both in New York I had the opportunity to get to know the dude a little bit, so it influenced me on a level of making me see the long game. So yeah, those and like a ton of other artists. I would’ve said Emory Douglas, Tadanori Yokoo, and Hirano Koga in terms of thinking about images, colors, time, but come to think of it, I’ve been thinking about [Mike] Mignola more recently, like with Hellboy in Hell.

Just in terms of a dope businessman, I’ve been looking at Ashley Wood. Yo, how does that work? This guy looks like he plays for a living, I wanna play for a living. “I’m gonna make these toys, now I’m gonna make this comic – there’s no real story, it’s just a buncha pictures.” [Laughs] I don’t want to do that but I want to know how he did it. He can make some great images too, but that aspect is what gets me.

These are the guys that I look at. [I read] a lot of comics, I know I mentioned Kelly Sue before. Those are more my inspirations, if I had to say my gods, the gods would be like Bernard Krigstein, Moebius and recently, and I feel weird about it, Joost Swarte. He does some covers for the New Yorker and does these weird design strips, just thinking about what they’re doing. Also Milton Caniff was a god to me when I first got out of school, but now I’ve been thinking about him a lot more in terms how how he tells a story – in segments and as a whole. You could fulfill my narrative needs in four panels, but also those four panels over the course of a year tell a larger arc. That to me is a level of art and craft that people don’t have anymore, you get just little bites of things. “You gotta buy the trade!” know what I mean?

CB: When does the art influence production and vice versa?

RW: There’s a bunch of films, but like I was telling Brandon this morning, I’ve been easing back on filmmaking as an influence on my work. I’m trying to study more of what’s unique to the medium.

CB: So how much about American comics are produced is focused around collecting to trade or getting movie deals – how does the major pipeline of of how comics are made in the US affect the work created? You might be better doing work in France or Belgium.

RW: Kind of, yeah. They’re certainly making a lot of work there, but that’s it’s own thing – they’ve got their problems. They’re not making movies out of comics, there is a market for people who just want to read comics, though maybe not as many as they’re making. [Laughs]

CB: Something I’ve been wanting to ask about is your amount of travel, especially to Paris or Japan. What are those trips to you because I feel like they’re more – they’re not sight-seeing…almost like a pilgrimage?

RW: You know its’ funny – maybe. I talked to someone the other day and she was saying how much she wanted to travel to different places she hadn’t been before. I felt self-conscious because this woman always me feel self-conscious. I really care for her so her opinions about things, even though they could be completely trivial, make me reflect on my own. So I thought why I haven’t gone to a bunch of new places, why do I find myself going back to the same places? I’m not touring, you know? Every place I’ve been, there’s been a reason.

My relationship with going to Japan originally was to meet the family of somebody I was with at the time. Then it just became something – my relationship with that person ended, but my relationship with Japan didn’t, so I would go out there and I have friends out there. With France, I got a residency. Another thing, those are the comic capitals of the world. You got Italy, you got Argentina. I would say Brussels but I feel like it’s the same family as France. I haven’t been yet though, but that’s the whole Franco-Belgian scene. In Europe, that’s kind of like the capitols. If they made it in Latin America or Spain, it’s gonna be in French. The same with manga, if it’s super dope and it’s manhwa or something- it’s gonna be in Japan.

CB: They’ll go to Comiket and do the whole thing?

RW: Exactly, exactly. Coincidentally, I ended up in those places. Is it a pilgrimage? Maybe. I don’t believe in touring but I feel like you gotta get outside your space a little bit. I’ve never been to the developing world, my whole thing is if I’m gonna go someplace, what am I bringing to it? Why am I going there, you know? I’m not just going there to look at people somewhere else because that’s some kind of existential experience for me. It’s real selfish and rooted in the privilege of being able to move. I went to France for work, I went to Japan for family and I find myself going back for those reasons.

CB: It’s an interface – you have to give and take equally.

RW: Right, like some hunter/gatherer or something. [Laughs] I had to go, there was a reason. So that’s why. It isn’t touring, I didn’t go to buy things, experiences or otherwise. I feel like it’s weird because once you’ve done it, the experience is almost enough to make you want to become that person who thinks “I gotta travel just to experience something new and different.” When in actuality, the way I’m evolving and growing my fixation on community, it’s very important not to leave and not escape whatever crisis you have at home by going somewhere else.

I’ve always been running, man. I ran from here to New York, but then I found New York and I don’t need to run anymore – that’s my home. You start out in Boston?

CB: Nah, born and raised in Michigan, moved to San Diego, went to school in Western Mass, and now I’m in Boston.

RW: Holy shit, that’s crazy.

CB: Yeah I haven’t gone back to Michigan, but I’ve stayed in touch with some folks. It’s wild to see how where you are always affects how you think. I see that especially with my friends back there.

RW: I think it must be difficult to be in that environment and see what our economic system has done to it. I was at a bar somewhere and we were talking about Detroit and folks were talking about how they wanted to go there and buy a house and my response was “you’re fleeing gentrification here to go to Detroit…?”

CB: “Can you do better?”

RW: Yeah, can you do better? Or are you going to the leave the problem that’s here and bring that problem somewhere else, passing on that oppression? Like when you’re walking down the street and you see five guys on the corner and they see a woman and start calling out shit. Now yeah, I understand, you’re economically and racially oppressed, but now you’re passing on that oppression to someone else, probably a black woman, doing the same thing to someone who may have it intersectionally worse than you do. So that’s how I feel about it. I feel super-romantic about Detroit – Smokey Robinson and Iggy and all that. I wanna go there and I wanna have the ability to start my life somewhere where it’s maybe a little bit easier. But this is my home and I’m gonna take care of it. I don’t have a reason to go to Detroit, I’m not just gonna go there on some pioneering thing – as much as I want to.

CB: It rings really imperialistic. “I’m going to start my life over yonder, no one’s there!”

RW: [Laughs] Let’s go discover Detroit! Yo I want to though, like I dig it. I feel like that’s intoxicating. I could take my money, go someplace else and spend it willy-nilly? Here’s the thing though, because of how capitalism works, someone is going to be affected by that, you know.

CB: It’s like the British blood in our veins telling us where to go and what to do.

RW: Right? Hey, maybe it’s my other ancestors going “Hey, don’t fuck that shit up. Don’t do it.”

CB: I remember reading an article about research into hereditary trauma – they were doing studies with the children of Holocaust survivors. Is that possible and how could that sort of thing affect us day to day?

RW: I thought they totally proved that ’cause at one point they were talking about how they could tell from your genes if your folks lived through a famine. As if it were recorded in genes.

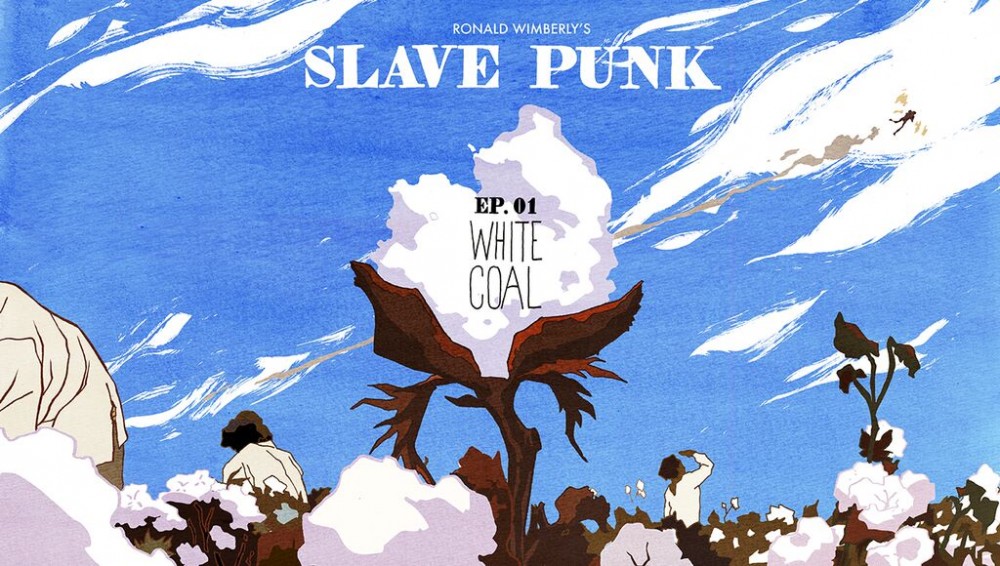

CB: On the note of heritage and trauma, what’s the word with Slave Punk?

RW: I’m cautious even talking to people about it ’cause it’s gonna be a while! It’s coming after Sunset Park so it’ll take some time.

CB: I only have one real question based off an interview you did with Paste where you mentioned that genre has rules and that Slave Punk is a genre. How has it been developing those rules?

RW: It’s funny ’cause when I started to think about it, it was when I was in college and a buddy of mine asked I was watching anime, which I wasn’t anymore. I was done with anime. He convinced me to check out Cowboy Bebop and I saw the intro and thought it looked cool but anyone bite off of Blue Note or Suzuki Seijun or whatever. Then I kept watching and realized the intro song is kind of a play on Mingus’s joint “Gunslinging Bird” and I’m like yo, I love this show because the entire thing is an exercise on genre, so the name means what it is. Like Cowboy Bebop/Gunslinging Bird, know what I mean?

I wanna do that so with Slave Punk; 1000 different things I was thinking about converged to make an idea and one of them was that. I love making the rules and I look forward to making them and then breaking them. I looked at the tropes of steampunk and that was one of the things that set me off conceptually. Thinking about about how our world is slave punk – in our world, the resource was free labor, whether you’re talking about housewives who couldn’t get paid for their work or couldn’t vote or you’re talking about slaves who didn’t get paid for their work and couldn’t vote. Maybe you’re talking about people who’re getting underpaid or not paid for their labor and that’s the world that we live in.

Going from that, I thought about the rules for this world and my take on the American Myth. What’s a more honest Myth for me? I remember hearing J.R.R Tolkein talk about how he wanted to make a Myth for England, a Mythology for the British people. We, Americans, already have that Mythology, it’s just it’s bullshit. So I thought, let me make my Mythology for America.

CB: Have you read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ new book?

RW: Yeah man.

CB: He talks about that Dream, yeah?

RW: [Laughs] Yeah, that’s the Dream – that’s the Myth. In that sense though, it’s kind of fucked up because he’s always talking about the dream and ultimately I think he believes in rejecting the Dream altogether, not erecting a new Dream. So maybe I want to create a whirlpool that cancels out that other vortex, but yeah I certainly don’t wanna create some romantic notion of blackness or being American or being indigenous, you know? I wanna create something that makes you think about the Dream as it is; something to incite thought. Play that incites thought, creative play. I don’t want to spin an illusion for you to get lost in, I don’t want to create something for people to buy toys of or whatever and not really feel the need to think about things anymore. I know that seems counterproductive to my own success in this system.

And I love toys as much as anybody else. Probably not. I don’t love toys as much as anybody else. [Laughs] I got four toys. I got a Zatoichi doll, two Canti from FLCL – a green one and some mad one from a graffiti artist with a tech jacket on. Something about robots with clothes on is cool. Just because you’re a robot, why wouldn’t you want to wear clothes? Especially if you’re modeled after humans and intelligent somehow?

CB: It sounds like you’re making “cognitive fiction”.

RW: Yeah, I don’t know. It’s an exercise for me – I’m gonna jog and I’ll have my kettle bells and shit and I hope that people see me exercising with it and want to try to routine a little bit and get their own exercise. I feel like if you create something that’s fully-formed and doesn’t incite thought, like if you tell someone something that’s super didactic and you give them the ideas and you give them the brand and they just need to buy into it – that’s dead work.

Work that’s alive gives you a little bit of the space and incites thought and that’s what people do, it’s natural for people do that that. That’s why they make fan-fiction, that’s someone exercising their brain with this world and in some cases, doing more with the world than the original intent pulled off. I see how this is just a fantasy about dragons or something, but I want to deconstruct gender norms with it. I want to build something where that could happen – I’d like the intent to be for that to happen.

CB: Well, that just about wraps up unless you got anything else?

RW: Well, look out for GratNin sometime this fall. I can’t really say a whole lot about the delivery method, but it’s something new and exciting. Then next year is Sunset Park, gonna knock that bad boy out, and after then is Slave Punk but don’t ask me about one of those yet. I need to finish drawing them before I can start dropping numbers and dates. I’m crafting something and I know it’s whack and I know it’s nice to drop it like Queen Bey “okay, here’s a new record right here” know what I mean? But it’s comics and we have a bad habit of not doing that, we’re putting the hype out and hopefully you’ll forget about it and then I drop a little present on the people who care about it.

I guess with Image people do pick things up first day, they’re in the store for it. My career hasn’t worked like that, so I need to maybe switch my mode of thinking.

CB: Very cool, thanks Ron.

RW: Yeah man, you too.

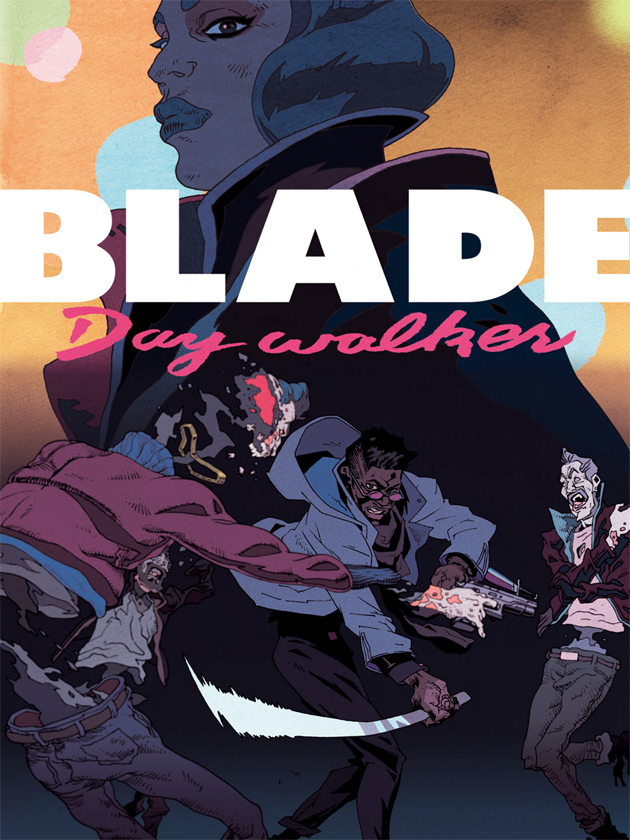

Ron Wimberly lives in Brooklyn, New York and creates comics. The above picture was his idea and I wouldn’t have it any other way. If you haven’t read it yet, be sure to read Lighten Up on The Nib. His upcoming works are the release of GratNin this fall, Martyr Loser King with Saul Williams at First Second, Sunset Park in 2016 with Image, and Slave Punk Ep. 01: White Coal also at Image with an undetermined release date.

There are different ways to look at gentrification. Like, you could probably move to Detroit without displacing any oppressed people–there are lots of empty houses there. Also, just as a person with an income, you could probably be a benefit to the community in Detroit, in so much as your local shopping would bring some extra revenue to small businesses that really need it. And depending on what kind of work you do, you might even help create jobs for other residents.

There’s probably a good long while when “gentrification,” or immigration of middle-class people, has a net positive effect on an economically depressed city, before it tips into being the sort of highly desirable place where only elites can afford to live and native residents are forced out, like New York or San Francisco. And of course many places never reach that stage.

Comments are closed.