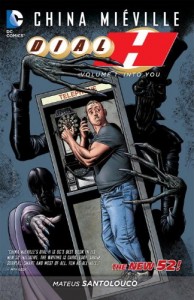

The classic Dial H For Hero is about a boy with a mysterious phone dial that turns him into a variety of superheroes when he dials the numbers corresponding to the word “hero.” The updated version is about a 20-something overweight, out of shape slacker who stumbles across a similar dial as his mobbed up buddy is getting a gang-related beat down. This leads him into a world of dimensional travelers, a sorcerer investigating null space and another person with a power-endowing dial.

Mieville being Mieville, the superheroes the dial conjures up are the likes of “Boy Chimney,” “Iron Snail” and “Cock-A-Hoop.” Surrealist and absurdest characters played straight, their bizarreness acknowledged as part of the plot. Yes, this is absolutely what you’d have called a Vertigo take on superheroes, had it come out a couple years earlier. It sits on the shelf alongside Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol and the more recent Xombi, in terms of the general feel of the book.

While Dial H plays it straight, there’s a sense of affection for the excesses of the silver age comics like the original Dial H For Hero. A knowing wink to goofy, stupid comics and an attempt to graft that goofiness into a more serious and modern tale.

The over-riding theme of the series is identity. What happens to a person’s identity when he starts taking on these mysteriously conjured superhero forms? Does the sense of self get lost in the memories of another persona? How freaky is it to find yourself in a form that doesn’t have arms and legs as you’re used to having them. I found the identity subtext to come out a lot stronger in the collected edition, than reading this as a monthly.

This book is divided into three acts: the first story arc and two one-offs.

The first act (issues #1-5) is the origin story, the tale of how Nelson Jent comes to be in possession of the dial, meets a fellow dialer, and also meets an ill-fated pair of dimensional travelers. This is a fairly dark story in tone and serves to introduce some mysteries around the dials from which the series gets it’s name.

The second act is issue #6 of the series. This is a comedic one-shot addressing the topic of old superheroes that aren’t exactly politically correct, as Jent becomes Chief Mighty Arrow, a bit of a stereotype. He agrees he probably shouldn’t leave the house looking like that. Much lighter in tone, this is a fun little piece of scenery setting, giving a chance to flesh out the lead characters and put a little context to the swapping of heroic identities. This story was most likely conceived as a placeholder with DC mandating special “zero” issues focusing on the past. It’s a pause before #0 and before the second real story line.

The third act is another one-off, this time issue #0. As part of an editorial mandate to tell origin-ish stories, this tale takes place in ancient times and shows a heroine activating a sundial and become a decidedly 20th century-looking superheroine to save her people. It also shows the aftermath as some more dimensional travelers come looking for her, both shedding a little light on and raising questions about where these heroes that the dial produces actually come from. The tone isn’t quite as dark as the opening act, but the seriousness co-existing with absurd characters returns.

Dial H Volume 1 is largely the set-up for a longer series, there is a story in it, but in many ways it’s like the pilot episode of a television series. An adventure happens, but more mysteries are uncovered than solved.

I enjoyed this volume quite a bit, but when recommending it, there’s a fine line that has to be talked about, especially given the current popular tastes in the market. That’s the fine line of camp. Mieville is dancing all around camp humor with this book, but he’s not quite going there. Instead of playing the hero that’s a hula hoop with a chicken head straight with the intention of getting laughs (in classic camp style), Cock-A-Hoop is played straight for surrealist effect and a wink to the audience. It’s a balancing act to acknowledge the camp without crossing over into it. Likewise the second act is something of a post-modern deconstruction of campy un-PC heroes.

If you hate camp, this might not be the right book for you. It isn’t really, but it plays with the concept enough it will be a distraction. If you want something weird/surreal and heavy/serious, again, this isn’t quite the right book for you. It’s played fairly straight, but the knowing wink is there. It’s a little hard to define, but that’s really Mieville’s calling card: turning conventions on their ear.

If you like weird and off-kilter, but you don’t need it to be 100% serious, this is a book for you. A few titles that might have varying degrees of synergy, besides Morrison’s Doom Patrol and Xombi, include Manhattan Projects, Chew and to a lessor extent, Prophet and Planetary.

wish this was promoted through vertigo so i would have learned more about it earlier. i definitely lumped it in with the random new52 titles i had previously never heard of and dutifully ignored it. the brian bolland covers probably should have tipped me off.

I can’t quite put my finger on it, but in terms of the obvious influence Morrison’s Doom Patrol had on Dial H, Dial H seems to be a deconstruction of deconstruction — a second-order metatext. It’s a little bit too risky to guess at what it all means at this point just because the story is still in progress, but I think that Mieville’s reluctance to use camp is smart. Playing the characters relatively straight when the powers they acquire through the Dial are absurd even by the standards of the superhero genre keeps me invested in the characters and thereby keeps me invested in at least *part* of the story and keeping me involved in the characters’ emotional journeys at the very least creates the *illusion* that I’ll have a chance of understanding the metatext, whether I ultimately will or not.

Comments are closed.