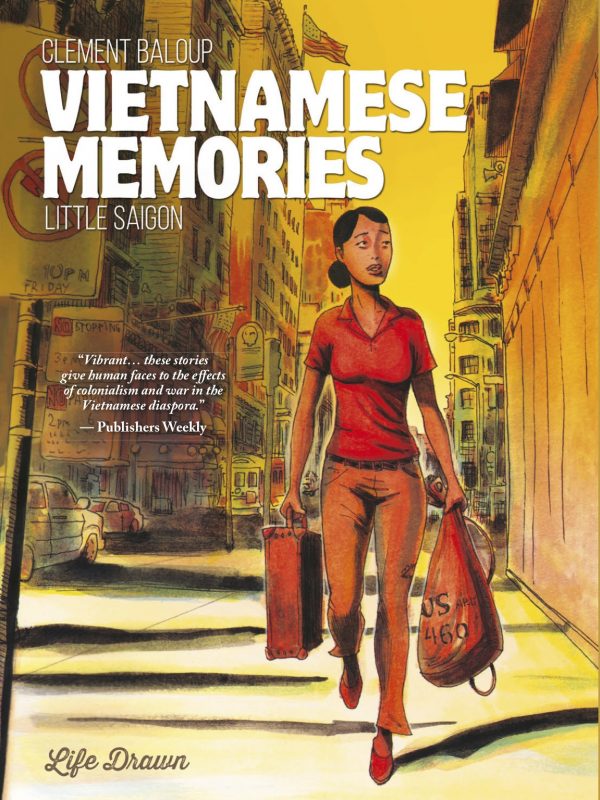

In the remarkable Vietnamese Memories Book 1: Leaving Saigon, the stories of the Vietnamese diaspora that Clement Baloup told were France-centric and so had as much to do with the horrors of colonialism as the war, with one of the most horrific and gripping sections documenting Vietnamese slave labor in the post-World War II years. He also tells the story of how his family escaped Viet Nam and came to France.

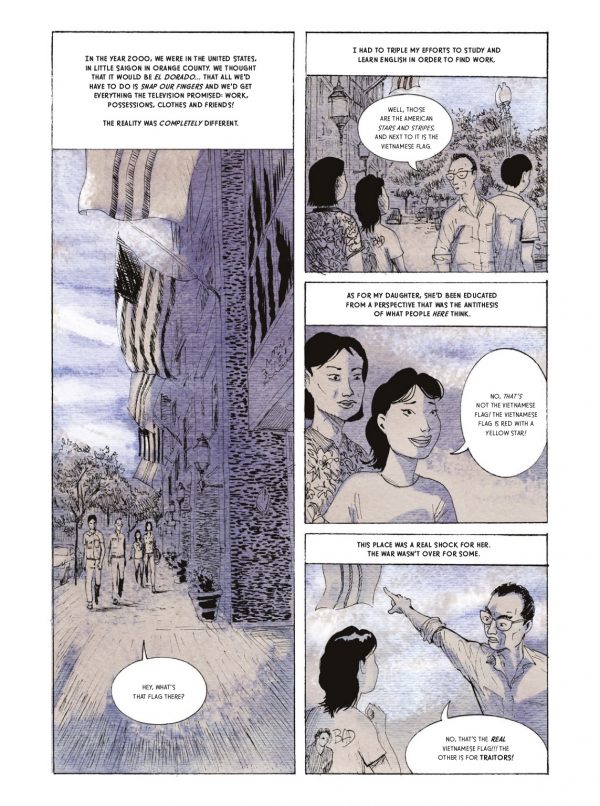

In this second volume, Vietnamese Memories Book 2: Little Saigon, there isn’t as much of a historically-sweeping quality, and it doesn’t delve too much into the specific relationship between the Vietnamese and Americans, though he does look at how Asian culture, in general, can become isolated from the American mainstream.

Baloup mostly opts to focus on the personal stories here, and they are as compelling and alarming as those in the first volume. The book begins on a happier note, though, during a visit with a Vietnamese chef in Brooklyn who walks readers through his recipe and process for making pho, which serves as a gateway for the stories he tells here, and which extends to become bookends.

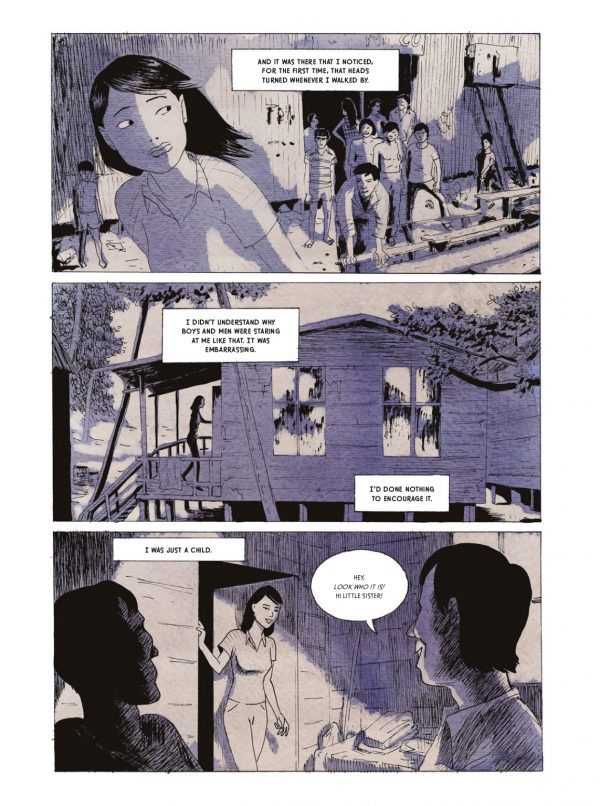

A trip to California brings him to two Vietnamese communities, both known as Little Saigon, where he uncovers people’s stories of assimilation and how they came to the area. This gives him the opportunity to briefly explore the experience of a gay Vietnamese man within the community, but mostly this section belongs to the glamorous Anh, whose appearance doesn’t betray a harrowing story of refugee camps in Malaysia and Indonesia, and assault at the hands of a fellow refugee.

In Los Angeles, Baloup enters a prosperous and modern-looking area that has grown much since the 1980s, when refugees were placed there and lived in a world of gang rule. That all changed when an American investor decided to build a shopping center to offer the residents the chance to pursue businesses. His hunch was that they would thrive, and he was right. It became a gathering place for the community, and as it grew, crime dwindled, becoming a much-lauded immigrant community success story.

An appointment at a massage therapist introduces us to the focus of this section, Yen, whose early days as an athlete in Viet Nam are disrupted by escape attempts, stints in jail and work camps, and an unplanned pregnancy, all conspiring to keep her in her home country for years before finally migrating to the United States legally.

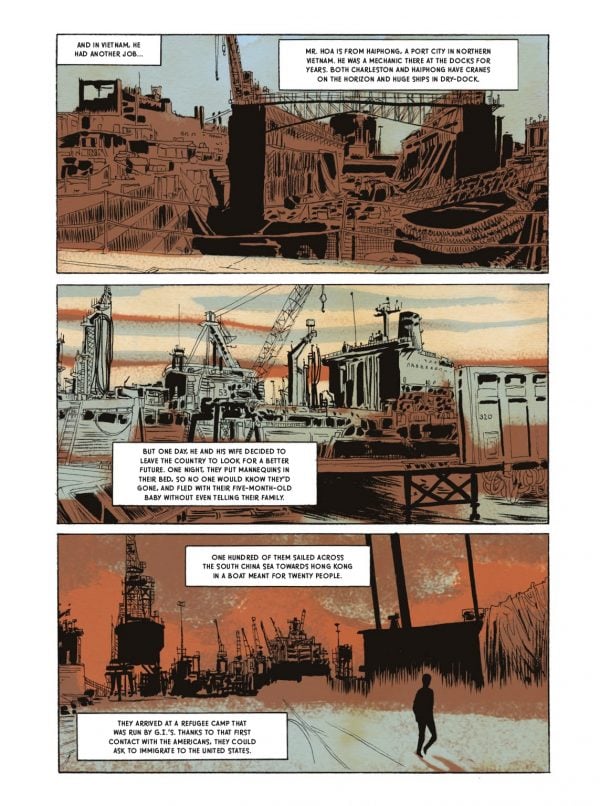

Baloup also visits South Carolina, where he meets the self-made Mr. Hoa, a realtor who sells shrimp on the weekends, formerly a mechanic in Vietnam who fled with his wife and child who fled to Hong Kong with about 100 others on a boat meant for 20 people.

Baloup then follows the harrowing love story of Tam and Nicole, who first met as teenagers in Saigon, where their neighborhood is in the grip of a gang war even as the more extensive conflict ravages the country. Separated for years after Tam is sent to France, Nicole lives a traumatic life of escape, marriage, betrayal, poverty, mental illness, and suicide before her happy ending eventually comes.

That’s really at the heart of what Baloup uncovers, both in this volume and the previous. Often, the person we see now gives no hint of the arduous journeys they took to their countries of refuge, nor the racism, assaults, or even enslavement that they faced.

That’s something to keep in mind in our current situation, where we see refugees and immigrants at the moment of transition, and some of us have decided to judge the whole situation from that slice of a larger story. People leave something and are headed somewhere, and the more we can listen to the stories of people who have lived through that complete process and can offer insight to the experience and advice on how to work with people coming into our country for the best possible outcome, the more immigration is likely to be a win-win situation.

Baloup unfolds these tales with a genial journalistic voice, and his artwork is stunning. Whether he is rendering the urban vibe of California, the stripped-down villages of Viet Nam, the horror of the refugee camps, or the food-focused energy Vietnamese restaurants, Baloup is a master of making scenery come alive and placing his subjects within them, making their bravery and dignity consistent landmarks within the unpredictable journeys portrayed here.

Comments are closed.