Story & Art: Yoshiharu Tsuge

Translation & Essay: Ryan Holmberg

Publisher: New York Review Comics

Who among us, in this age of rapid development, 80-hour work weeks, and gig culture, isn’t familiar with burnout? How many of us struggle with our own feelings of inadequacy, the inability to feel as though our accomplishments mean much when we’re encouraged to rapidly move on to the next project? This isn’t a state reserved for Millennials, or even for the 21st century, though it has certainly become more widespread and more readily discussed.

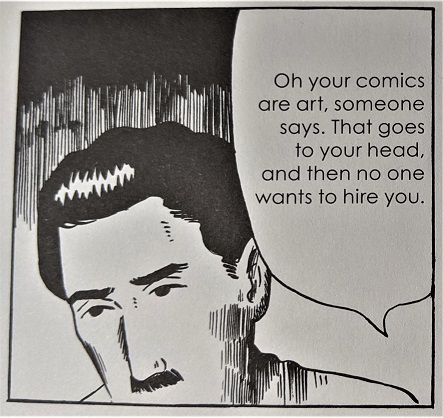

But in the 1980s, mangaka Yoshiharu Tsuge was feeling similarly disenfranchised with his work. A successful creator in his own right, he also spent many years working with the incomparable Shigeru Mizuki, providing assistance when a deadline was approaching and Mizuki needed some high-quality work done. But for many years, Tsuge just didn’t want to make any new material.

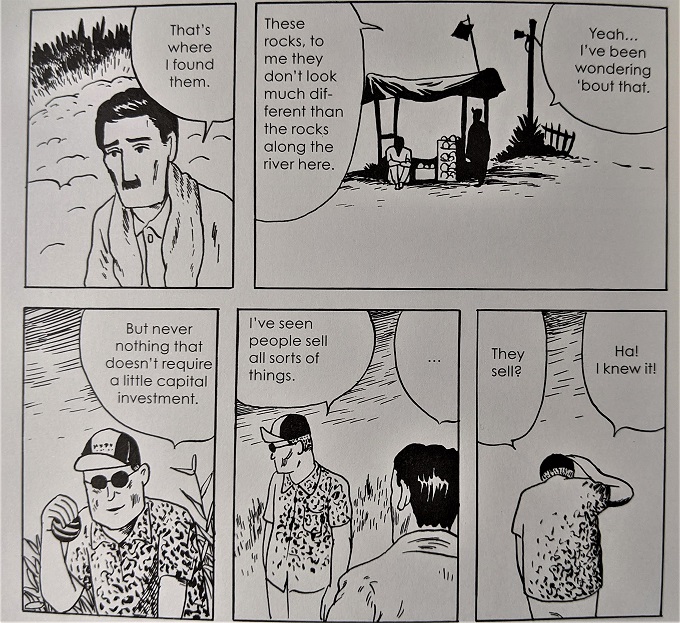

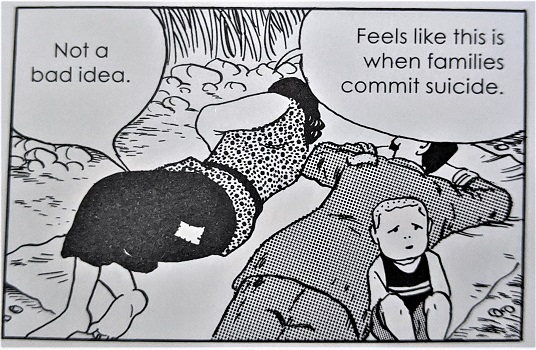

And then, seemingly out of nowhere, he came out with The Man Without Talent, a semi-autobiographical story that follows a former mangaka as he tries to find new, bizarre ways of providing for his family. Sukezo Sukegawa, Tsuge’s cartoon stand-in, spends most of his days down by the river, attempting to sell the stones he found along its banks to passers-by. But no one is interested in rocks they could easily scrounge up themselves, so Sukegawa never makes a profit. His put-upon wife, forced to hand out fliers for work, is constantly pressuring him to write another manga. She believes this is the only thing he’s really good at, the only way he can support his family, and doesn’t understand his reluctance to do it again. His young son is consistently anchoring Sukegawa to reality, picking him up from work when he gets distracted and even preventing his suicide attempt.

Sukegawa is not a flattering avatar for Tsuge, depicted as shiftless, stubborn, and a tad haughty. He constantly has excuses for not making manga, complaining that there is no art to it anymore, not like there was when he was in his heyday. His fights with his wife are uncomfortable, especially with their young son watching from the sidelines. Everything his wife says is fair, but her depiction as a nagging harpy, though perhaps a product of the time, makes it even harder to take Sukegawa’s victimhood seriously. Sukegawa, however, is also not a particularly accurate avatar for Tsuge who, as translator Ryan Holmberg’s essay at the back of the book elucidates, very much enjoyed reinterpreting his personal life to find a deeper truth (and whose fights with his wife were apparently much, much worse than Sukegawa’s). In this case, Tsuge highlights the struggle between soul-sucking, banal poverty and the desire to lead a simple, peaceful life.

The narrative seems cynical, and in many ways it is. But there is a humor here, too, to be found in the nonsensical get-rich-quick schemes Sukegawa is continuously attempting, from fixing old cameras, to selling decidedly ordinary stones, to ferrying tourists across the river on his own back, heedless of personal dignity. The Man Without Talent allows the author and the reader to explore the fantasy of leading a contemplative life; but where other authors would laud such a lifestyle, Tsuge is bitterly honest about how such a lack of responsibility affects those around his protagonist while simultaneously proposing that there are too many demands in modern society.

The Man Without Talent is the first of Tsuge’s works to receive English-language publication, though his younger brother Tadao Tsuge has seen modest popularity among comic book literati. As is often the case with books of this nature, the supplemental material — essays and imagery from the authors’ works — helps to really place the manga within time and context, making this an excellent read for anyone who wants to know more about early underground/art manga history.

For those who wish to experience the fraught catharsis of lazy living without burning all the bridges in your own life, The Man Without Talent, out January 28, can be preordered through the New York Review Books website. Keep an eye out, also, for The Swamp, a collection of Tsuge’s early works which will be available through Drawn & Quarterly in April.