Americans are made to be well aware that the big wide world is fraught with danger. Especially for Americans. When we hear about murders, abductions, and slavery of all types, it’s almost always in regard to an American being murdered or abducted or made into a slave. That’s part of the narrative we sustain for ourselves that operates as cautionary, of course, but also separates us from the rest of the world with the implicit understanding that these things don’t happen here, these things don’t happen to Americans.

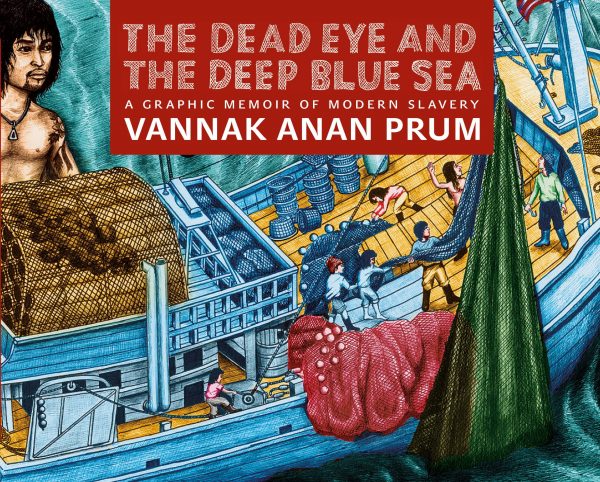

Well, they do, but that’s not the point of The Dead Eye And The Deep Blue Sea, which instead brings into question why, if these things happen in other countries, don’t we typically pay attention to those stories? Why aren’t they the cautionary tales we tell?

Vannak Anan Prum doesn’t exactly answer that, nor should he have to, but this recounting of his own experience as a slave does point out the vast canyon between the experience of an American dabbling in the dangers of the world and someone who lives there and is the more common prey.

Vannak lived through the horrors of Cambodia, born in 1979 and grew up during the bloody conflict between the invading Vietnamese army and remaining Khmer Rouge forces. Spending his young years on the road, in the military, and in a monastery, Vannak was an avid artist, eventually marrying and settling down. In a desperate attempt to find work after his wife became pregnant, he went to the border of Thailand and did not return home about five years.

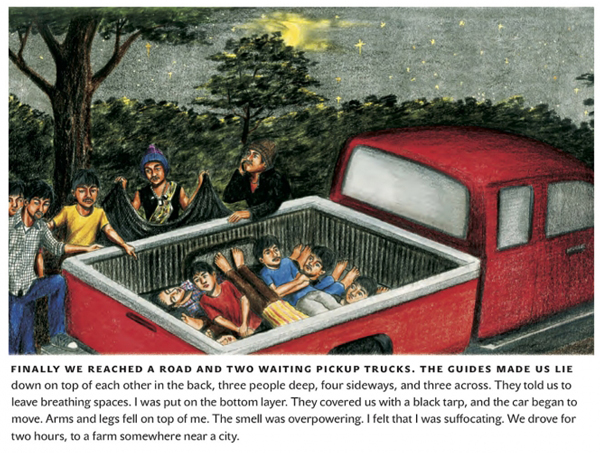

Vannak spent those years as a slave and prisoner. The majority of the time was spent aboard a fishing boat where brutality was the order of the day and the psychological effects of only seeing ocean surrounding you began to play tricks on your perception of what the world was. Vannak also spent a shorter amount of time as a plantation slave in Malaysia and then within the prison system there, unjustly incarcerated because of corruption.

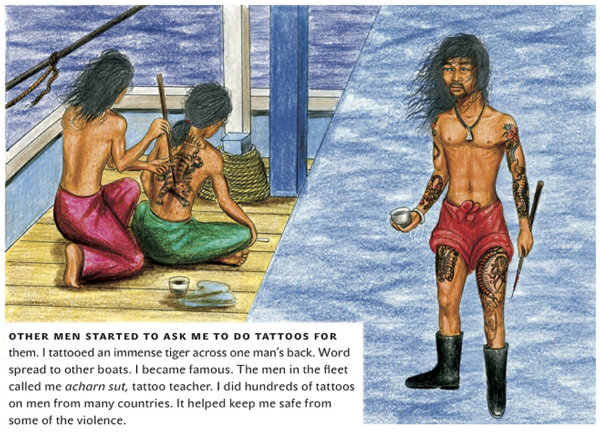

Part of the reason Vannak was able to survive had to do with his artistic skills. Drawing opened people up to him in a friendly way and often created connections when he would draw that person. His talent translated into a practical vocation as a tattooist to his fellow slaves, which secured some side money and other items, including a camera and a cell phone. Mostly, though, Vannak’s strength was his patience, his ability to wait things out and act according to carefully thought out plans, to strategize in his interactions with his owners and fellow slaves, and to think quick at moments when many would succumb to self-destructive emotionalism.

Vannak’s memoir is a straightforward telling of his experience, though his insights and eye for detail are engaging even amidst the horror, especially in his meticulous drawings. There’s a lot graphic in here, but not gratuitous — honest and evocative are the words that come to mind. And Vannak’s narrative displays the same patience as his survival does. His reflective, calm tone guides the reader through some truly upsetting horrors, revealing the very qualities that got him through the trauma.

The horrors of the slave trade are to be expected, but I think what is truly jarring to a white westerner is the institutionalized nature of that trade, of it its weaving with governmental departments and law enforcement. It is a well-oiled machine and it uses the organizational structures created to serve people against them, and this reality makes it plain why it’s so hard for the victims to combat their captors. It’s more than isolated slaveowners. It’s an entire system that protects the slaveowners and keeps the slaves in their places, silent.

We need more stories like Vannak’s, but we also need them to be told as skillfully and passionately and creatively as Vannak tells his, and we need this to happen until these stories are no longer eye-openers, but narratives we accept as common and pledge to take real action to prevent. And we have to have an interest beyond how it affects Americans on vacation. These boogeymen we fear are easy for us to tune out. That’s a privilege too many people don’t have.