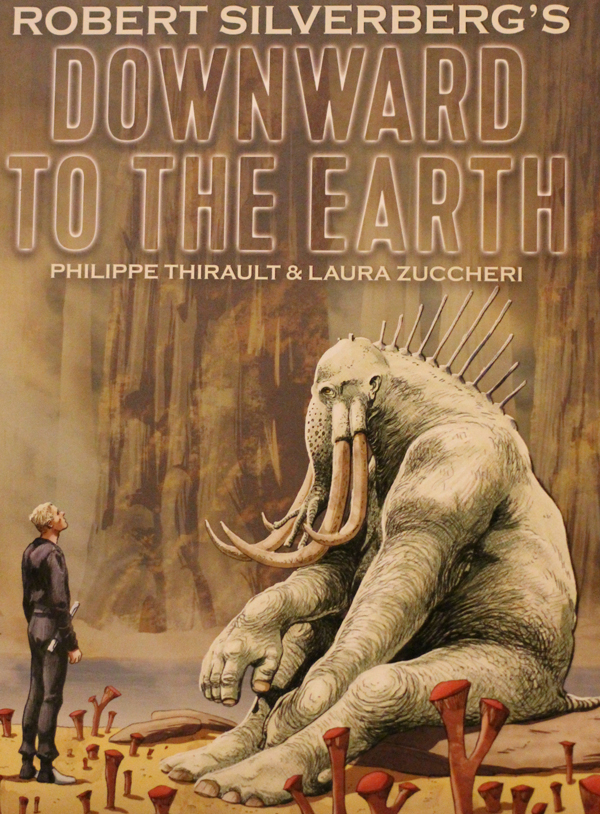

Adapted from Robert Silverberg’s 1970 novel of the same title, writer Phillippe Thirault and artist Laura Zuccheri face the challenge of helping the nearly 50-year-old science fiction novel seem not so outdated. Not story-wise, necessarily, but affectation-wise — characters, situations, actions and general tone. Traditional white guy-penned science fiction at the era was not always the most wonderful venue for portrayals of women with depth. And the often cerebral aura of works back then don’t always translate well to the more dynamic science fiction styles of the 21st Century.

Taking place on the planet Belzagor, the story follows returning former military occupier Eddie Gunderson as he guides a married duo of anthropologists to a secret spiritual ceremony of the native inhabitants, the Nildoror and the Sulidoror. The planet was previously a vehicle for humans to procure and export venom from the naggiar, a giant jungle serpent monster, a miracle drug that regenerates tissue in humans, but this trade seems to have ended once the planet was handed back to its inhabitants.

As well as the skeleton of colonialism, Gunderson’s emotional past lingers there as well, his old sins ready to demand retribution, and the people he crossed years before sit in wait for the unexpected chance to strike back for his transgressions against them. Chief among these are his old commander Kurtz — a nod to Heart of Darkness — and Gunderson’s ex-lover, Seena, who married Kurtz after Gunderson abandoned the planet.

Silverberg’s novel is renowned as an examination of colonialism and its lingering effect on those colonized, as well as on the colonizers. In this way, it’s certainly told from the conquerer’s point of view, but the idea is that the masculine enterprise of dominating people has left the former foot soldiers aimless and emotionally bankrupt once the domination stopped. The colonial structure gives the masters something to measure out their lives with, and its absence sends the former human masters into a spiritual spiral.

As is so often the case with former oppressors, they fixate on the mystical qualities of exotic beings and believe they can appropriate these aspects for their own development. In context of Silverberg’s tale, this takes the form of several of the human cast eventually partaking in the alien spiritual ceremony with the understanding that past digressions can be wiped away, a second chance can be given.

These rebirths are important to the humans as both a chance to put their part in the colonial efforts behind them, as well as function as a “Get Out of Jail Free Card” for their personal sins. But in order to gain this quick fix, they have to perform new versions of the same disingenuous actions from before. No alluring alien exoticism can save them from themselves.

At its heart Downward to the Earth is a good old-fashioned science fiction tale hearkening back to a time when cosmic was the operative word for several levels of any given scenario, like a throwback to Heavy Metal magazine. Zuccheri does a remarkable job at offering a fully-realized planet for the human escapades, while Thirault does the best he can with the women. Sometimes the marriage of the two eras of science fiction can be awkward — sometimes the expletives in the dialogue feel forced and out of place, for instance, and its embrace of “deep” spiritualism can feel dated — but that doesn’t deter from the general enjoyment.