Sometimes it’s better to just give yourself to something rather than to seek out its meaning. Not everything has to have one clear meaning, and in some cases, to bring concrete meaning to a work might mean imposing clarity on something that was not meant to have any. That imposition might actually come off as an insult, and the better approach might be to accept it on its own presentation, to let it be what it is.

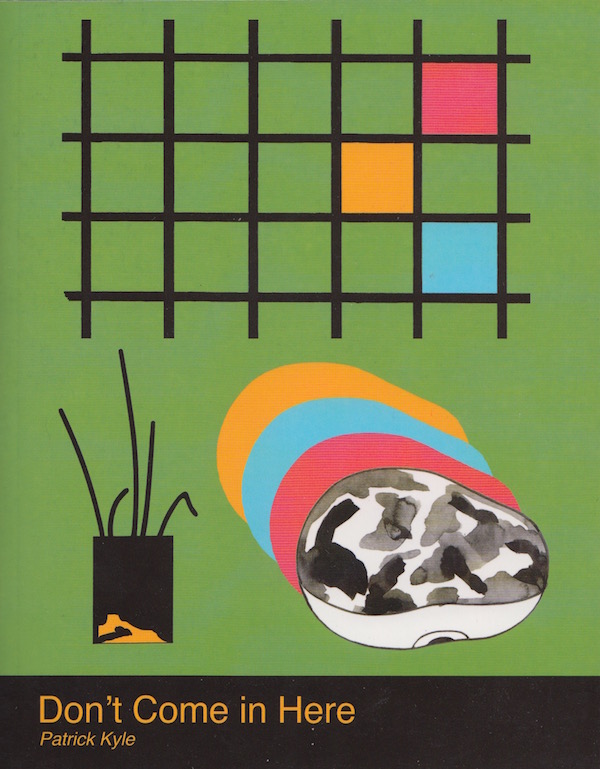

I understand the above might be confusing, but it won’t be if you’ve read Patrick Kyle’s Don’t Come In Here. The first indication that attaching meaning to Kyle’s work is not the point of Kyle’s work is the title itself, a direct instruction to not go any further, to not enter within its insular space. No investigation, no interpretation required.

At its most basic, Kyle presents the story of a guy in an apartment, talking about different things in his life. The guy and the space around him is presented in an abstract and spare way, often simple lines with simple features that feel like geometry manifesting itself as narrative. The has no distinct facial features and the only real information we have about his personality is that he is familiar with The Simpsons. Enough to dream about the show and deconstruct its narrative perspective in a telling way, anyhow.

His only two relationships are with his landlord and with his computer. The landlord hands out some general instructions about living there and then moves along, hardly caring about the guy. The computer is the exact opposite, picking up on the despair that oozes out of the guy, offering the best advice the computer can give based on the way the computer would handle it, as well some soothing words about feeling safe in your own space. Sometimes, the computer can a little indignant, though, and this certainly jostles the trust between them.

Kyle renders this dynamic via varying degrees of abstraction, from panels where you know what it is but don’t know what is going on exactly, to those that are jumbles of lines or symbols or patterns. All this is matched with a witty narration that grounds the visuals when they get a little too obtuse.

This isn’t for everyone, not by a long shot. Even compared to some of Kyle’s previous work, this could be considered hyper-experimental — his graphic novel Distance Mover, for instance, was downright linear by comparison.

If you like absorbing creative work without a specific emotional or intellectual goal, if you like letting the work sit for awhile before a comprehension of what you encountered begins to appear, if you like creative work to function in collaboration with you, to fashion something unique and personal between you and the work itself, then Kyle’s concoction is possibly for you, and you will be able to encounter it in a way that’s enriching.

So I’m not going to offer any answers for you here. I see Don’t Come In Here as a text that needs revisiting and meditation. If you need rigid form and definite answers, if anger is your reaction to opaque creations that demand some work on your part, if you have nothing of yourself to give the artwork, you should probably avoid this.

Comments are closed.