From Moses to Mad Max, wandering in arid desert lands evokes a journey for self, for destiny, and of course for survival. Usually it marks a transitional place in the wanderer’s life — think of the Aboriginal walkabouts in Australia that are conducted in the passage from youth and into adulthood, but also stand as a marker of a spiritual move forward.

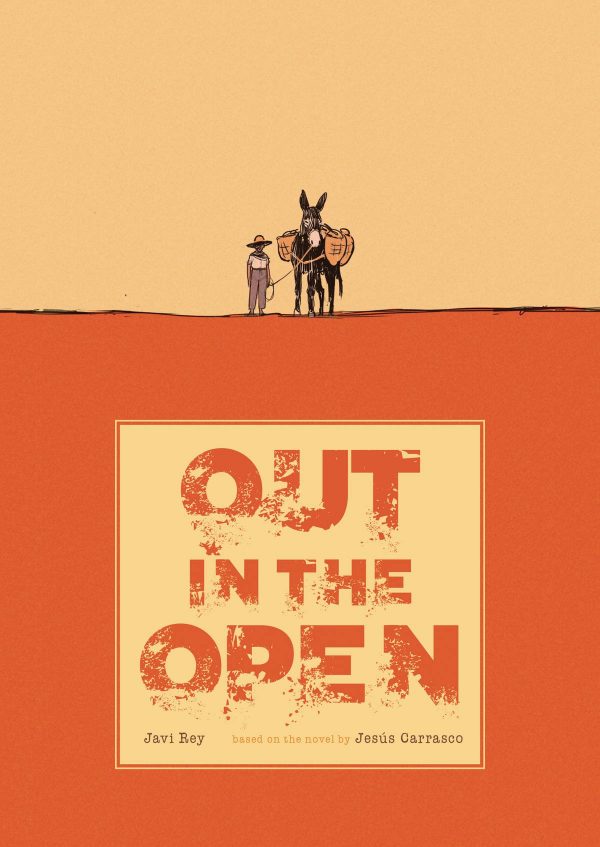

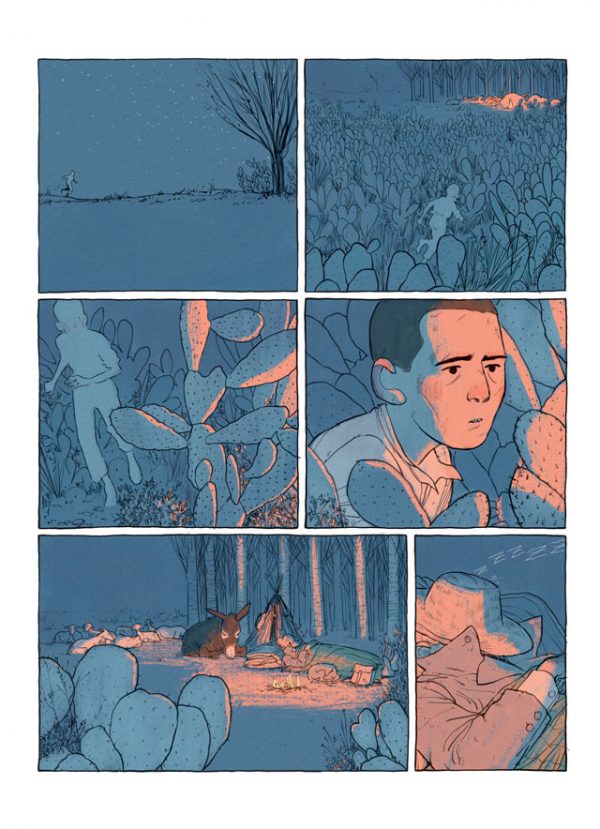

Based on a novel by Jesus Carrasco, Belgian cartoonist Javi Rey’s When Out in the Open opens with a young boy who lives in a small, rural town hiding in fear as his neighbors start a relentless search for him. It’s led by the boy’s father, who — we find out — plays the role of the innocent to convince the people to find his son, though his son’s violent memories of him reveal the opposite of that presentation. The boy is also fleeing the Sheriff, presented in the boy’s perception as a fire-red devil being with razor-sharp teeth, ready for flesh.

When night falls, the boy flees and comes upon a campsite where he tries to steal food, but instead ends up tagging along with the campsite’s owner, an elderly and rugged goatherd who wanders the land. For reasons that are incomprehensible to the boy, the goatherd takes the fleeing boy under his wing and sets him up in an apprentice relationship as the boy helps with chores and begins to learn aspects of the work.

This is not a chattering duo and their wandering life through the drought-stricken land unfolds amidst a blanket of silence between them, with only scattered exchanges, usually having to do with work to be done. But the goatherd also functions like a mysterious guardian angel, and on occasions when the boy is almost uncovered by his pursuers, takes care to keep him safe and free, risking his own safety. And even in this moments of heightened risk, the story maintains a calm quality that brings for a zen-like unfolding of the danger, as if it realizes that this is what happens in life and like anything else, even danger must be approached with calm and intentionality.

That transition I mentioned earlier is very much in evidence as the story escalates. The boy, at first, is attached to the old man and the connection is unlikely to be severed. The old man comes up with clever ways to separate, all chore-related, but soon the boy is off on his own in larger intervals, still somewhat chore related, but with the narrative purpose of showing how much more capable he has become. Though at the beginning of the book he depends on the old man to protect him, that relationship grows more equal. When he finally faces the evil that he is running from, it’s a final moment of symbiosis between the two, and the transition soon comes full circle.

The quiet of the story puts the onus on Rey’s visuals to get across the narrative, but the contemplative nature of what unfolds suits the art very well. Rey uses his paneling to express the action, but also to get across the internal as it relates to the external. The land is the soul and Rey’s choices of focus provide an emotional barrenness that is realized through physical tokens. Pain is a process through which the opposite can be achieved, but it’s a slow, debilitating one that begs focus and clarity to make the full journey.