On one hand, Garlandia has all the charm and intimacy of the characters from which it pulls obvious influence, the Moomins — the book is dedicated to them, alongside Moebius and Fred — but it takes it to darker, more expansive spaces than the Moomins ever go. Perhaps that is where Moebius comes into the equation, his influence stretching this fairy tale of creatures known as Gars into massive epic territory that as much in the realm of Tolkien as Tove Jansson.

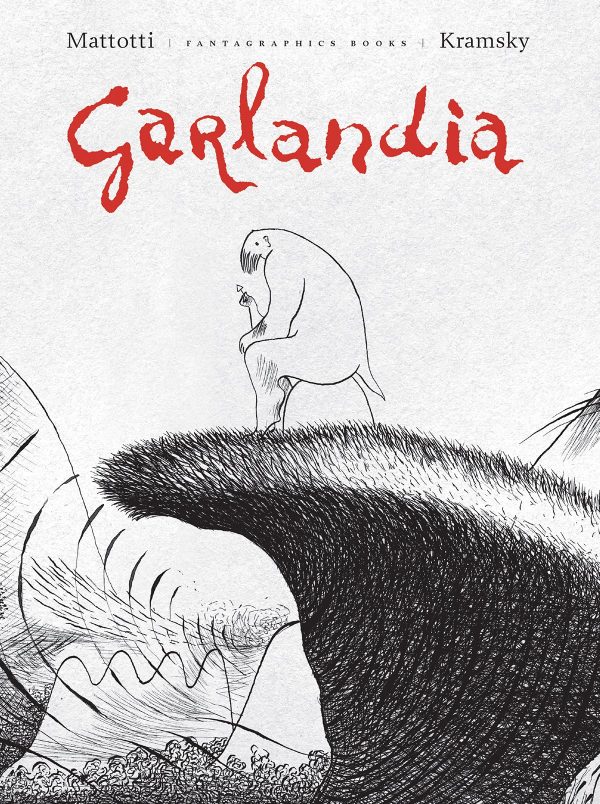

With text by Italian writer Jerry Kramsky — a pseudonym for Fabrizio Ostani — and out of control, explosive art by Italian artist (based in Paris) Lorenzo Mattotti, the proportions of Garlandia’s narrative are hinted at mostly through its length — at 400 pages, there’s bound to be something in there. But you never quite expect what you find filling those pages, part pastoral fantasy, part grand journey that becomes a world-building triumph.

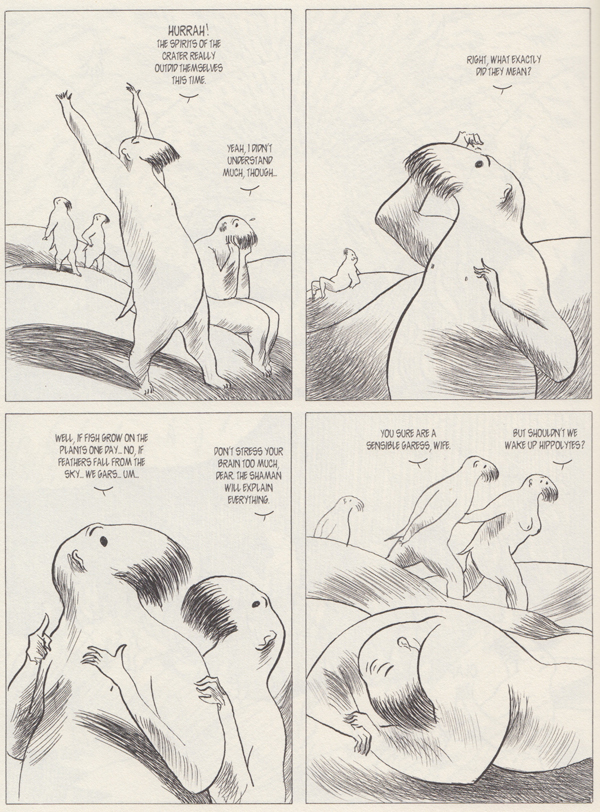

The Gars are a society of bipedal creatures with chubby animal bodies, innocent eyes, and whiskery growth around their lower faces. They seem to do a lot of aimless lazing about and talking to other magical manifestations in their world, but they also have a number of strange rituals that they regularly attend to, like the Spirits of the Smoke who are expected to appear at the beginning of the book to reveal the future of the Gars.

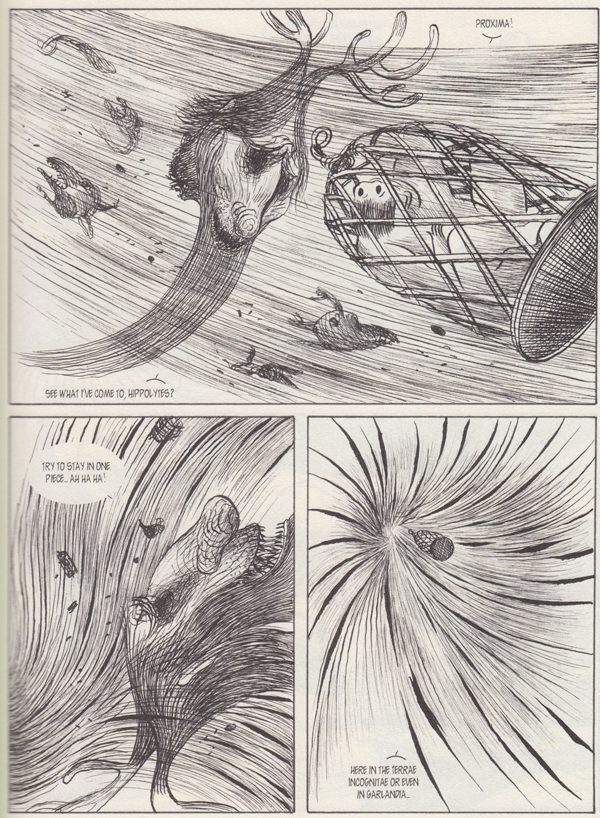

That future comes to light in a chaotic sky show swirling smoke, careening bodies, and geometrical abstractions that all burst from the page thanks to Mattotti’s kinetic line work engulfing the panels and expressing the mass vision of the Gars without giving much in the way of physical totems on which to hang what we are seeing. The Gars try to interpret what we’ve witnessed, but their ideas collide into frantic pronouncements of doom that their shaman, Zachariah, must think about. The one thing he does know is that change is coming.

His son and our hero Hippolytes finds this out all too well when he gets word that his wife Cochineal is with child and has taken to the Nesting Lagoon, where all Gars give birth. A quick decision made by Hippolytes on his way to Cochineal sets off a chain reaction which brings about the predicted change with a fury that plows through whatever pastoral pleasantries the Gars have been clinging to. And when the Gars want explanations for the destruction, they latch onto the most obvious change they see — Hippolytes and Cochineal’s child, Albina — as the focus of their own revenge.

Kramsky and Mattiotti build this already sturdy situation into an excuse for two separate adventures that remain intertwined, but entirely on their own tracks, which in turn gives the opportunity to explore not only other denizens and customs of the world the Gars inhabit, but also some of the beliefs and metaphysical concepts within that world.

But even as the story becomes expansive, it remains grounded by centering it around the travels of either Hippolytes or Cochineal. And rather than wrapping those journeys around constant heroics to create adventures, perseverance becomes the more operative trait of the two new parents, determined to find each other and save their child and, in effect, work towards a greater future despite the tumultuous adversity that they accidentally unleashed.

Kramsky and Mattiotti do a great job of capturing an entirely alien world and keeping that quality as central even as we get to know it better. But the relationship between Hippolytes and Cochineal, the emotional connection between them and the commonality of parenthood that exists as an abstract, new bond between them, keeps the far-out adventures in territory any of us can grasp onto. This is especially important as Mattiotti’s line work, sometimes reminiscent of children’s book illustrator Bill Peet, but by way of Ralph Steadman, makes the indescribable entirely present and the unformed completely expressed, placing these right in front of you in tangible forms and yet still challenging you to understand what exactly you are looking.

Comments are closed.