In The Danes, Belgian cartoonist Clarke’s suspense-thriller with science fiction tones, takes an accepted apocalyptic trope, a devastating pandemic, and turns it upside down. In most stories like these society collapses because of a desperate battle for survival against disease, but in The Danes, it’s the fallout of racial animosity exploding because of a disease.

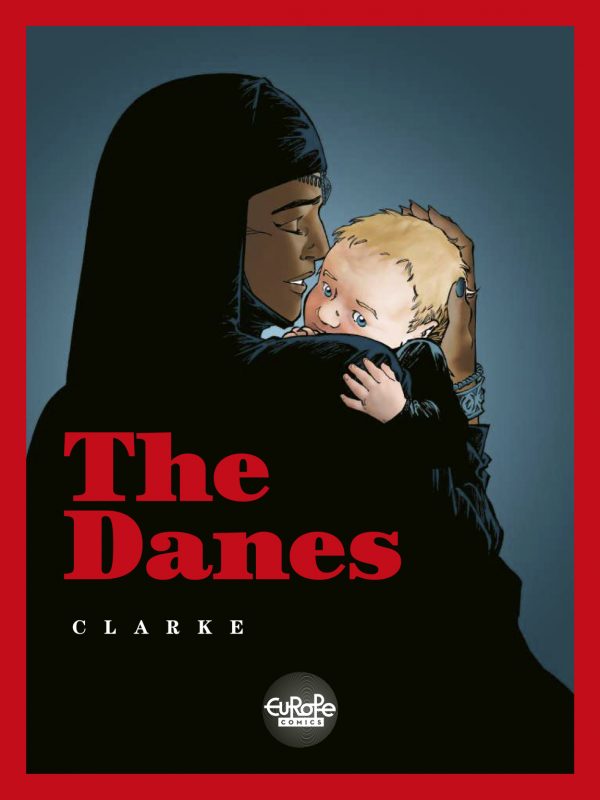

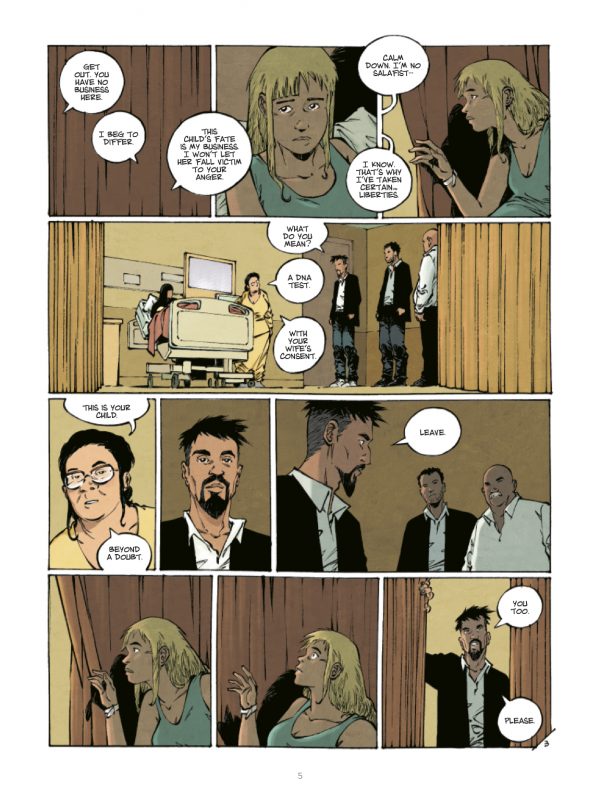

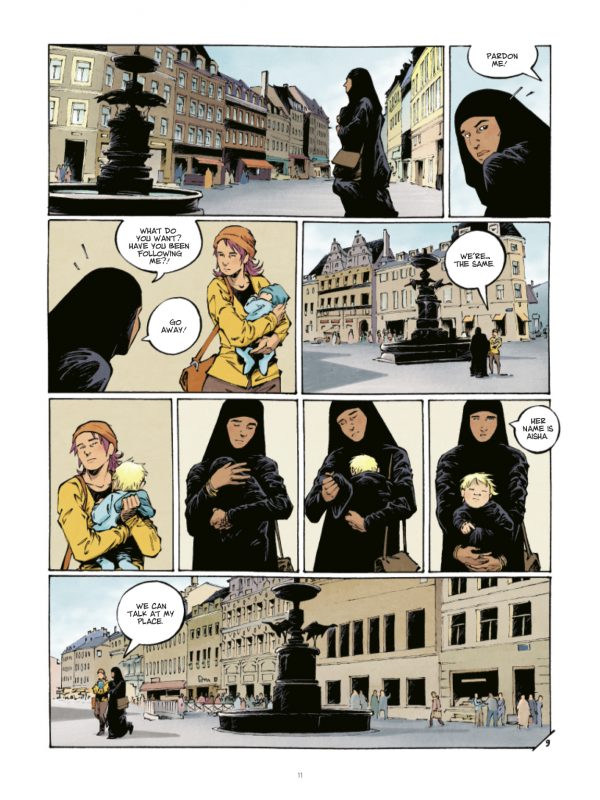

If you’ve ever seen Village of the Damned, imagine something like it on a continent-sized scale, sweeping through Europe and causing violence to erupt. We’re introduced to the problem on a more intimate level, though, when a Jordanian woman, Sorraya, in a maternity ward in Copenhagen gives birth to a blue-eyed, blonde-haired girl. Taken as a sign of infidelity, she is rejected by Sorraya’s in-laws, but when a nurse reveals that a DNA test has been taken and Sorraya’s husband is the child’s father, the science can’t override what people think they see in front of them.

Across the room in another bed is Kirsten, who has also given birth to a blue-eyed, blonde-haired baby. But Kirsten is Danish and no one thinks anything of it. She knows better, though, and so does her husband. The child is proof of infidelity — a DNA test prove that and so does Kirsten’s personal knowledge of who the father is, but the race dynamics involved make the situation less of interest.

That casual prejudice is going to prove crucial as more and more blue-eyed, blonde-haired babies are born first throughout Denmark and then begin to spread across Europe, developing into a full-blown societal panic that has pharmaceutical companies pushing for vaccines before they are ready and using them to manipulate profits, while immigrants are attempting to flee for fear their future children will become victim to what becomes known as “the blond virus.”

While Sorraya and Kirsten are at the center of the drama, there is also Martin, the ne’er-do-well who stumbled upon the evidence of the pandemic early and has hidden the details from the authorities, and Jorgen Brandt, a journalist trying to figure out what is going on.

There is a level to which “the blond virus” is a silly disease, no arguments here, but it’s a fanciful one that works to prove certain points, highlight various themes. In the culture of the European right wing, an onslaught of Aryan babies seems like it would be a dream come true. But the question remains whether the focus of hate is on appearance or genetics. Is a person of color genetically a person of color or is all that’s needed to make the difference a change of skin and hair?

We know that race is a construct — in particular, a construct of white humans who created a deep-seated form of differentiation often for purposes of control, enslavement, colonialism, and, of course, as a justification for hate that often evoked pseudo-science.

It would have been simple to portray a situation where only people-of-color find their children becoming perfect Aryan types, but by making it a situation that everyone faces, including white people, Clarke, who is better known for his humor comics, orchestrates a situation where racists are faced with the reality that those they hate not only become what they most worship but by virtue of an across the board transformation, they become equal to a racist’s own child. How can you differentiate between people, how can you claim one person is inferior to another when everyone looks like a racist’s vision of perfection? What channels can hate find to thrive in?

At the same time, the people of color, the immigrants who do find this happening in their families, are faced with dilemmas themselves. Is this virus essentially an erasing of racial identity? If somehow the condition brought equality, is the price worth that equality?

Clarke never overplays these questions but rather lets them hang there in the story to infect the action. This keeps it from becoming too profound, which is a shame, but they do function as provocative subtexts for an enjoyable suspense comic.

At its root, The Danes is the story of two women with completely different lives who find themselves in a situation where they need each other, and the bond they create because of this perhaps transcends many of the questions being posed. The larger message, rightly or wrongly, is that understanding and empathy happens organically, though sometimes that means it never happens or happens too slowly, and that is perhaps part of the tragedy of the human condition.

Only on Amazon for Kindle? bother.

Comments are closed.