In the fantasy series Geis, the European fantasy tropes are given a run for their money in a sort of It’s A Mad Mad Mad Mad World style parable of power and authority, by way of the Grimm Brothers, and through the lens of breathtaking illustration work that captures wonder and darkness together

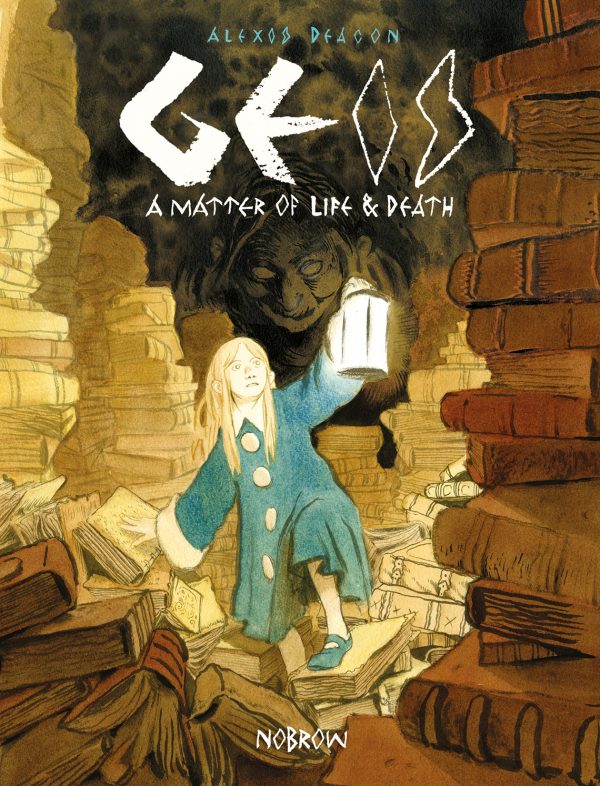

In the first volume of Geis, subtitled A Matter of Life and Death, the passing of the chief leads to a contest for the next chief. But the contestants find themselves the objects of a trick and the stakes in the game are higher than they imagine. Alexis Deacon does well to splinter the trials into individual stories that come together in the end, gliding on some whimsical fantasy but injecting it with real darkness and vigorous action, all spinning around a sorceress who conducts the trials but also manipulates and transgresses the purity of what the competition is hoping to achieve.

Well, maybe. Maybe the manipulation and transgressions are part of the ultimate reckoning.

It’s a remarkably full-realized book and Deacon draws you in with the adventure and the personalities swirling within it, but never gives into the common fantasy story-telling temptation of making everything too complicated. The implications of depth within the world, including more to the characters and the situation than meets the eye, are there, but Deacon never lets it roughen the tale being told.

At the center of Deacon’s crowd of contestants is Io, the Kite Lord’s daughter, who finds her own inclusion in the competition to be a mystery. Introduced as a humble, unassuming addition the contest to be chief, Io proves to be the hero of the story, with her compassion leading her onto action and bravery, and causing her to make a tough decision with the well-being of the wider group of contestants in mind.

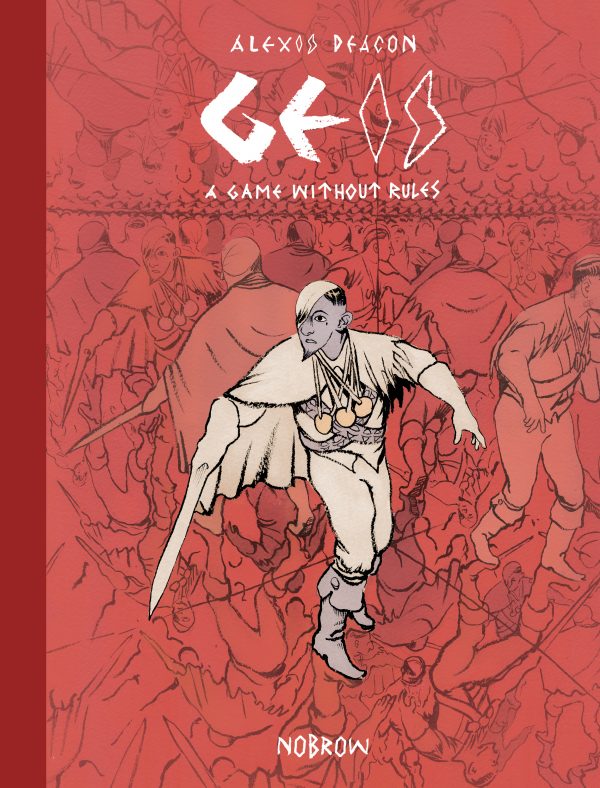

In Volume 2, A Game Without Rules, the competition is taken to its next level, and the center is broadened. Io, incapacitated for much of the story, makes room for more examination of the other players, particularly her direct rival Nemas and his personal struggles for power.

The challenge in this volume is as much brain teaser as free-for-all, in which the various stories start wrapping around each other in an attempt to create bonds that will overcome the demands of the sorceress. The idea is that the participants, or maybe combatants is a better word, are tasked with creating their own rules for their own games and using these to defeat the opposite team in the struggle.

It’s a valid challenge to pick a leader. A good leader should be able to create structure out of chaos, since that is problem-solving in a nutshell. In Deacon’s depiction, the law is held forth as the most obvious manifestation of this idea. The law is structure from chaos and, as related through the judge who takes some charge in this volume’s struggles, the law is a system put in place that can allow the weak the stand up to the strong. That the strong survive is the law of nature; that the weak can revel against the law of nature is the law of humankind.

A Game Without Rules shows that Deacon is not content with putting forth a fantasy epic asking questions about right and wrong, black and white, about stark dichotomies with obvious moral choices.

Quite the opposite, in fact, and that’s what places this series as a relevant fable at a crucial moment. In the world right now, the strong, as represented by money and muscle and oppression, are making their move, and we’d like to think that what stands in their way is reason, order, structure, all the components that make-up the human invention of fairness.

In Deacon’s world, the very same unfolds as a fantastical struggle in a magical castle, with hopeful participants persisting in a rigged game. But it’s a dark castle, just like it’s a dark world, and the light may not be so easy to find in order to allow it to guide us, but as Deacon shows, though dim, if you’re determined, you can still find that light in each other.