Jeff Lemire has become quite a prolific comics creator since 2008. He’s largely devoted himself to the varying forms of genre fiction that comics offers, both his own creations, like Sweet Tooth or The Underwater Welder, and the classic characters of DC and Marvel, though sometimes his superhero work was defined by its quirkiness, like Frankenstein, Agent of S.H.A.D.E.

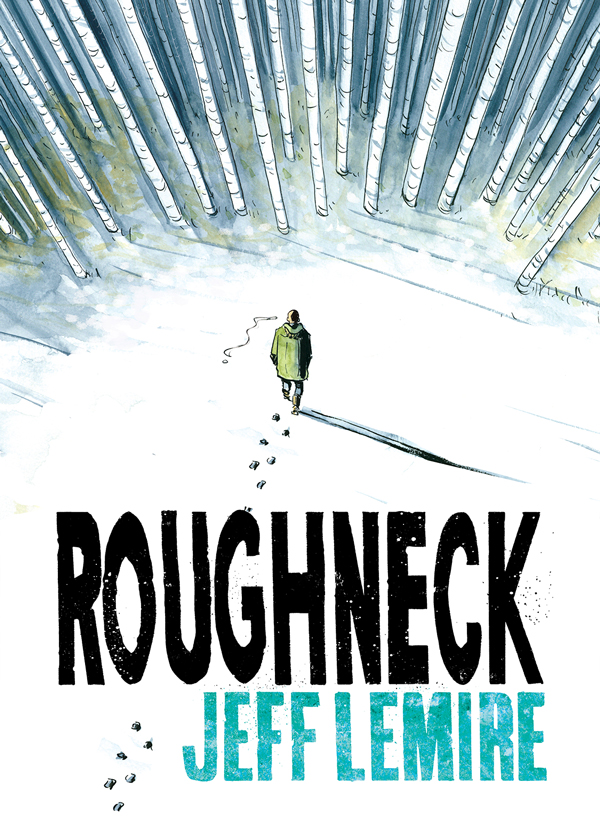

But he first came to my attention and the attention of many with his award-winning Essex County Trilogy, a dark, extremely human slice of the Canadian soul, and though he’s done fine work in the years since then, I’ve yearned for Lemire to make a return to his Canadian gothic presentation of rural Canada, and Roughneck is it. Wrapping together the circumstances of the Essex County works — rural desolation, poverty, hockey, childhood trauma, self abuse — Lemire offers an examination of broken people, with a concern for the issues of Canada’s native population, that could easily take place in Essex County.

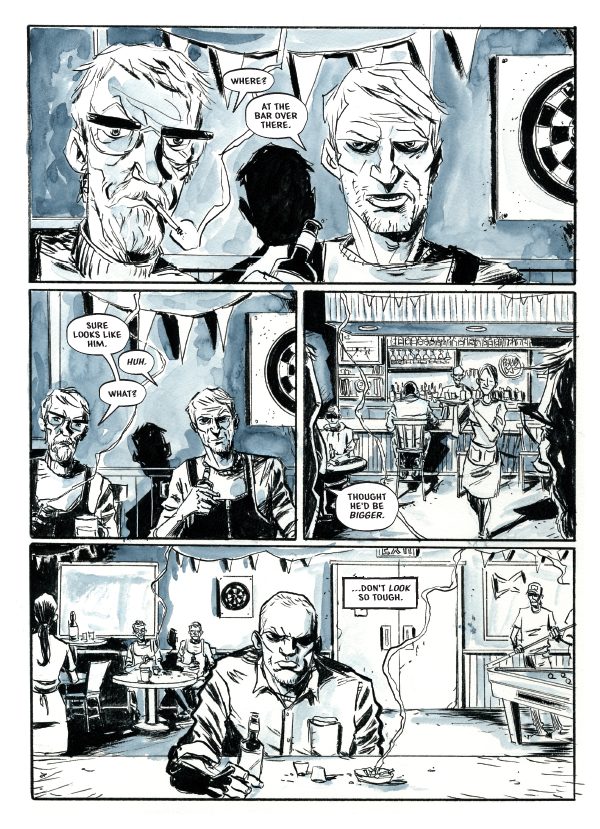

The story centers on the tortured soul of Derek Ouelette, once a promising professional hockey player, but now a captive of his own demons — a washed-out alcoholic whose possibilities are continually toppled by his dependence on violence to solve his personal problems. Now he haunts his hometown of Pimitamon, Ontario, driven by rage and humiliation, and dependent on the pity of old acquaintances to take care of himself.

Derek is going to be forced to face all these demons when his sister, Beth, returns to town after years of estrangement. She’s got her own version of Derek’s damage — a drug addict, pregnant, and on the run from an abusive boyfriend. Derek is determined to not only help his sister, but to save her, but in order to do so, he’s going to have to save himself from himself, and not create the very obstructions that always prevent him from keeping things together. And then he and his sister are going to have to face their destructive childhoods together.

Lemire’s writing is plain spoken and he leaves his poetry for his artwork I’ve always admired the craggy, worn faces of his characters as they walk within grim landscapes that so often reflect their psychology. There’s a hopelessness to the Lemire’s visuals, which is not to say that his stories are about hopelessness, but his art does reflect the way his characters approach the world. Even when things are good for the characters, their faces still reflect the world weariness brought about by the harsh reality they inhabit.

Unexpectedly, Roughneck is a work of hope rather than despair — or, rather, the relationship between the two. The intensity of hope, and the elation of achieving its goals, are perhaps relational to the lows of despair. The lower despair brings you, the higher redemption makes you feel. In that way, hope can perhaps be compared to the addictions of both Derek and Beth, but it’s one that strives to pull you out of the hole that typical addictions only trick you into thinking you are escaping. Lemire’s understanding of this, and his ability to connect the landscape of the body with the terrain of your emotions, shows what a line any of us can walk, and how perception can be a self-fulfilling prophecy.