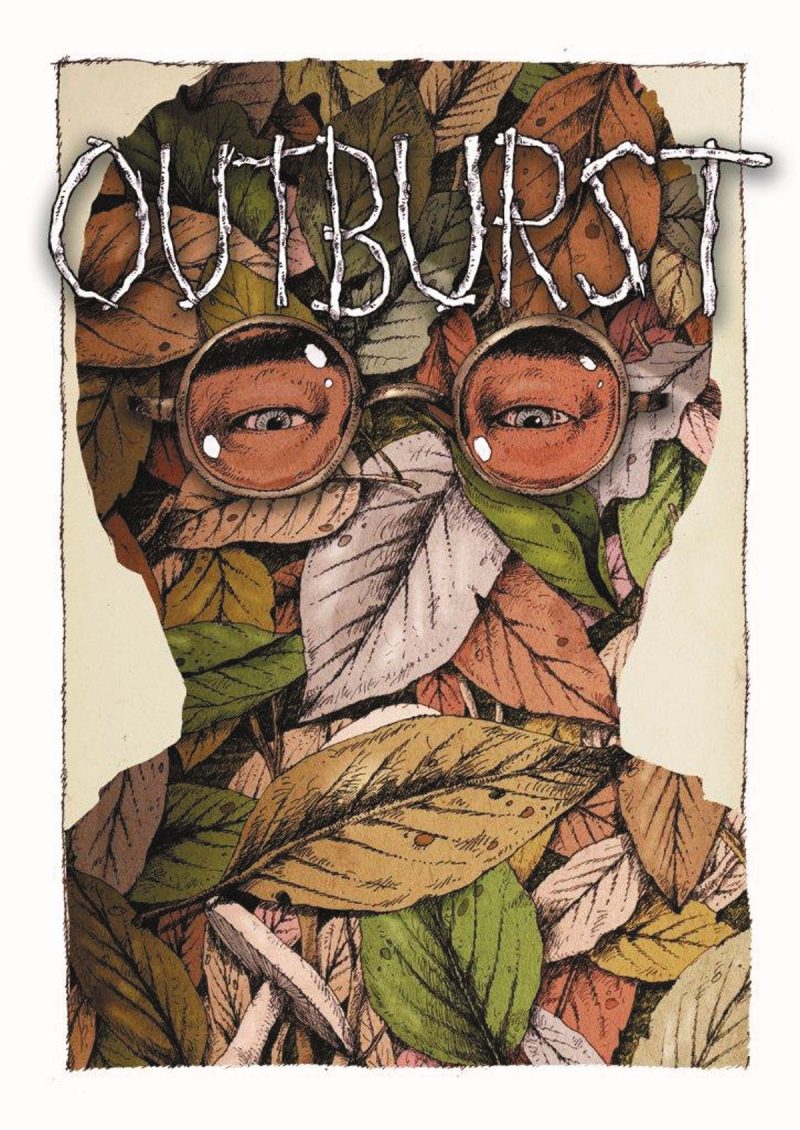

Walking a line between a depressing coming of age tale and a Kafkaesque expression of emotional hurt manifesting itself physically, Outburst ends up twisting both of them together into a probably inevitable horror finale. But Pieter Coudyzer does ask an interesting question — what if your place of respite is also an affliction that tortures you and drives you to the brink?

The story centers on Tom, who relates his younger, tortuous school days as a fumbling dork with a kick me sign written on his forehead that fellow schoolmates take to heart, relentless in their cruelty, whether it’s words of ridicule or practical jokes meant to humiliate him. Tom has a crush on a classmate, Aure, that typical unattainable girl who barely knows Tom exists.

Tom’s world changes on a school trip to the forest, when he takes a kayak out and becomes lost and stranded. Quite the opposite of panicked, Tom coolly deals with his predicament and discovers the isolation of the woods, and the wildness of it also, has a healing effect on him, and all the problems and emotions that torture him in his daily life disappear. It’s the kind of calm he has never before encountered.

Something changes in Tom after that trip, but not in a good way. I won’t go into detail, but there is a physical alteration that begins to overtake him and control not only what he is capable of accomplishing in life, but wraps itself around his mental health as well, an all-encompassing constriction to his well-being.

His disease reflects the forest itself and you have to wonder whether it was the freedom, the calm, that triggered an allergic reaction to the site of those, or if it was the forest itself luring him in with temptations like limitless emotional elbowroom and an escape from persecution only to infect him with its own poisons. Tom spends his life connected to those moments in the woods, projecting a fantasy-like trope onto his experience that is at odds with the sickness he walks away with.

As a result, Tom is further pummeled down just by his original sin of existing at all, and his physical disability sends him to a moment of ultimate humiliation, followed by a final act of revenge that seems unintentional and the result of years of hurt compiling inside him. If his goal remains what it always has been — escape — then it is at a cost. As a child on a trip to the woods, he was an innocent, but that changes and he never quite comes to term with the metamorphosis.

Obviously, this is a fable for growing up, and the forest stands in for that first moment we realize that childhood is not all there is to life, and we capture our first flavor of what adulthood holds. But as any adult will tell any teenager, being a grown-up isn’t what it cracked up to be. Childhood issues remain in your body and put a whammy on you at the most inopportune moments, often steering you into actions and reactions that you thought you had outgrown.

Coudyzer is very clearly stating that it does not get better. And in some cases, he’s certainly right. We all have a psychological version of what Tom battles with physically, and we all, just like Tom, battle to keep it under control sometimes in even the most mundane of everyday circumstances.