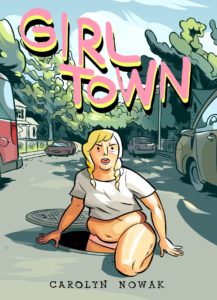

Welcome to Queerness in Comics, a bi-weekly column by Avery Kaplan that will explore queer representation in comics. This week, Avery is exploring Girl Town, a collection published in 2018. Girl Town was awarded the 2019 Ignatz Award for Best Collection.

Publisher: Top Shelf Productions

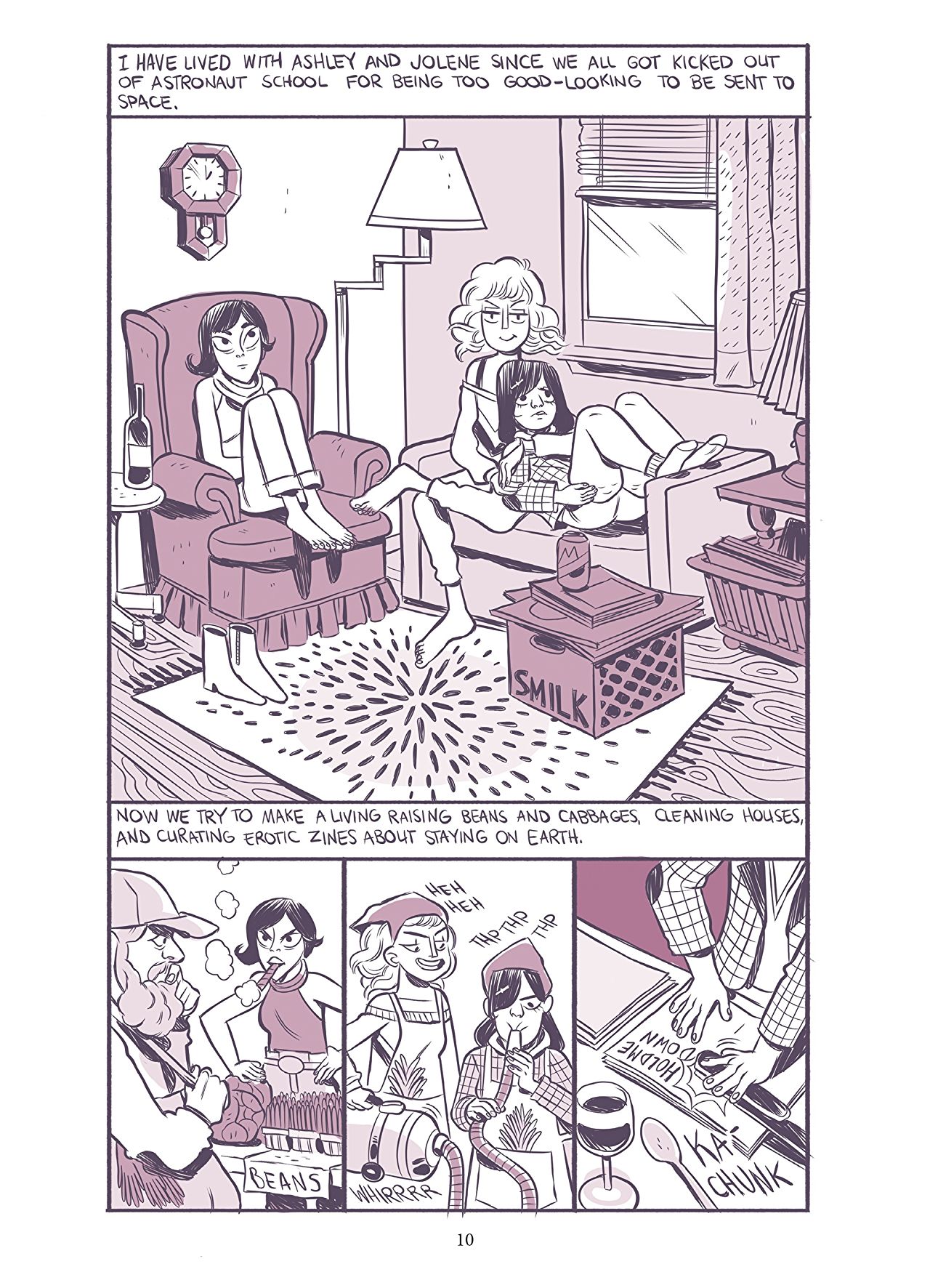

There’s something about Girl Town by Casey Nowak that has you hooked before you’ve even finished the first page of the first story (also called “Girl Town”). Maybe it’s the “smilk” carton, or the incredibly expressive faces of the characters, or the fact that the narrator of the opening comic begins by explaining that the roommates had been “kicked out of astronaut school” as a consequence of being “too good looking.”

While the idea of astronaut school is raised again, it’s never fully developed, which becomes the standard for the genre ideas in the book. They are mentioned and may be used to deliver the characters to a particular point, but they are not explored further than their explicit narrative purpose dictates.

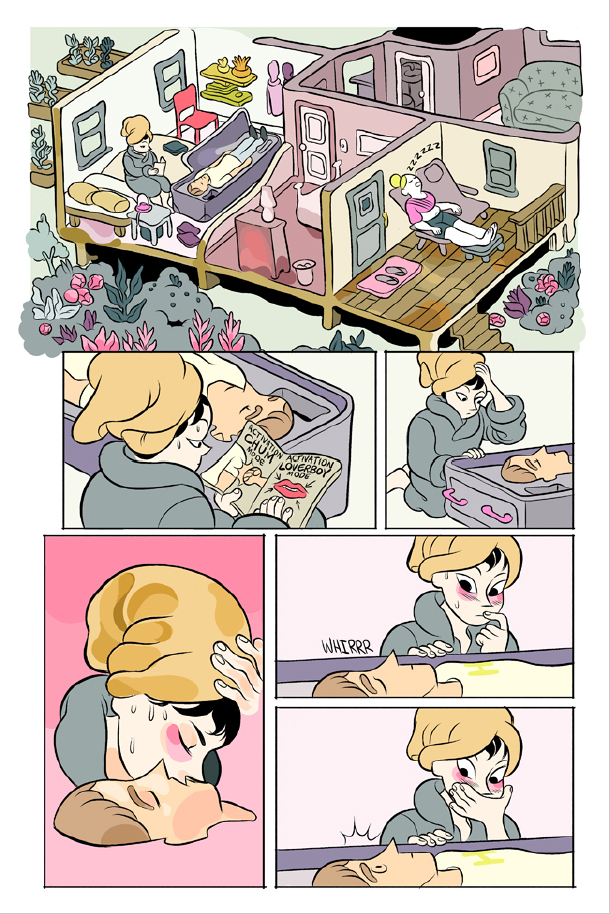

It’s important to note that while the genre elements may not be fully explored, that doesn’t mean that they aren’t developed, and given plenty of detail. One example is the robot boyfriend in “Diana’s Electric Tongue.” After a bad breakup, Diana replaces the boyfriend-shaped hole in her life with a Harbor series companion.

While details like the apparent development of artificial intelligence are not raised by the comic, there is still plenty of world-building that goes into “Harbor”: from the packaging to the marketing and the instructional materials included with the new robot, a lot of detail regarding the robot has been considered. However, the details explored by the text do not extend beyond those that are relevant to the perspective of the protagonists of the story (in this case, Diana’s interest in Harbor doesn’t really extend beyond how he functions as her boyfriend).

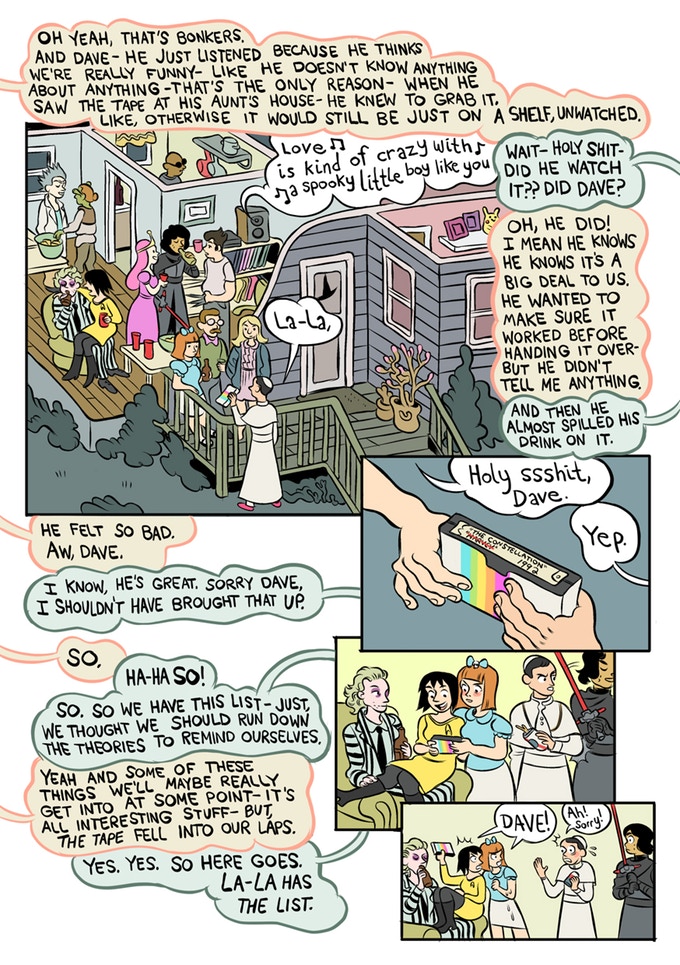

Another one of the comics in the collection, “The Big Burning House,” takes this principle even further. The story is structured around two friends recording a podcast about a cult film that almost no one has had the opportunity to see. As the dialogue exchanged between Mary and La-La propels the story forward: The Constellation was shown three times in 1992, there is controversy concerning the nature movie’s ending, and the characters recording the podcast have acquired a VHS tape of the film and are going to watch it. Throughout the story, images of people posting online about the movie add additional context, and the appearance of multiple “websites” carves out a frame that allows the fictional movie to take shape in the center.

By the end of the story, the resolution of The Constellation is still ambiguous to the reader, but the narrative function of the movie has nevertheless been served: what’s important isn’t the content of the movie, and ultimately, the vague shape of the movie – created by the frame of online conversation – is sufficient for the purposes of the story. The glimpses provided of the online presence of the movie contextualize the conversation between Mary and La-La.

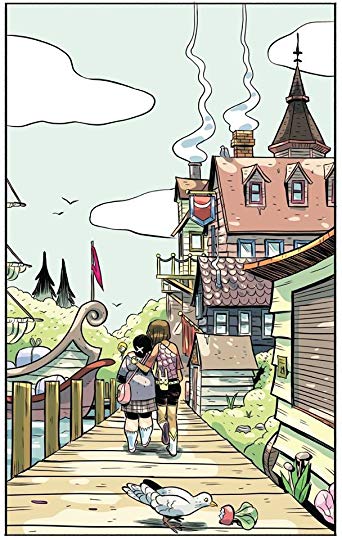

Another example is the setting for “Radishes,” a story in which Kelly and Beth spend the day at a market that seems to be set in a fantasy kingdom – however, while the adventure the pair shares at the marketplace involves a grooming session with a tiger and a buffet of apparently magical foods, the details of the nature of the world are neither provided or needed.

This basic blueprint of determining precisely how much information the reader needs to know and then stepping directly up to that line (but not over it) is also applied to the relationships between the characters. In “Please Sleep Over,” for example, the nature of the relationship between Gwen and Jess is never given an explicit label. While Gwen and Jess do share a kiss after Jess helps Gwen put on her makeup, the text never demands that their relation to one another be explicitly quantified.

But while the precise nature of their relationship may not be stated, the intimacy between the characters is deep and evident – a statement that can be applied to almost every one of the stories in Girl Town. The fact that these relationships aren’t given specific labels, however, does nothing to mitigate their power. While the reader may not be able to apply a single label to the bond shared between Gwen and Jess, for example, the bond itself is obvious and undeniable.

Girl Town excels at revealing the truth of these relationships to the reader. Just because longing isn’t given a name doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist, and being unable to explicitly say you love someone aloud doesn’t erase the fact that you long for them, or love them, or wake up thinking about them first thing every morning. Girl Town is wise enough to know this is true, but rather than try and explicitly state it, it avoids explicitly stating these facts to the reader and allows them feel it, instead.

You can follow Casey on twitter to keep up with their work and support their art directly through their patreon page.