Although Alan Moore had finished with Miracleman, it wasn’t the end of the character, or the comic. Knowing he was nearing the end of his story, Moore had rung up Neil Gaiman and asked him if he wanted to take over the title. Talking to Kurt Amacker of the Mania.com website in September 2009, Moore said,

By the time I’d got to the end of the third book, there had been such a lot of doubts and suspicions and angry words exchanged, and I was happy to wash my hands of the entire project and hand it over to Neil Gaiman. And, I told Neil, ‘This may well be a poisoned chalice.’ And, I remember saying to him, prophetically, at the time, ‘I’ve got no idea who owns Marvelman.’ I said, ‘For all I know, it might still be owned by Mick Anglo.’

Speaking to George Khoury in Kimota! , Gaiman said,

In late 1986, Alan had seen Violent Cases and a couple of things I’d written that wound up never seeing the light of day. The phone rang one day and a voice said, ‘Hello Neil, it’s Alan. Listen, mate, I was thinking how would you like to do – when I’m finished – would you like to take over writing Miracleman?’ My heart had a chance to stop beating entirely. He said, ‘Now, I should warn you by the end of Miracleman #16, I will have solved all crimes, ended all war and created an absolutely perfect world in which no further stories can occur. Do you want to back out now? Please feel free.’ I said, ‘No, I’d love to.’

At around the same time DC editor Karen Berger was in London looking for English comics talent, in the wake of Alan Moore’s work for them on Swamp Thing. Gaiman pitched various stories involving old DC characters until he hit on Black Orchid, a character so obscure that it took Berger a while to realise it was actually one of theirs. This led to the three-part prestige-format Black Orchid miniseries in 1988, and eventually to Sandman, beginning in 1988. So, although his work on Miracleman appeared after he started work on Sandman, it was actually something he had undertaken to do almost two years beforehand. [You can see Neil Gaiman’s contract with Eclipse, or ‘Writer’s Agreement,’ here, on Daniel Best‘s excellent 20th Century Danny Boy blog.]

A few years beforehand, Eclipse had reprinted various old Miller-era Marvelman stories in two different titles. In December 1985 they published a single issue of Miracleman 3D, which reprinted Moore and Davis’s framing device from Marvelman Special #1, along with three of the four older stories that had appeared there – all printed in blue and red ink, and formatted for 3D, which Eclipse were publishing a lot of at the time – but replacing Marvelman Family and the Invaders from the Future with Miracleman and the Exiled Gods, as they’d previously used Invaders from the Future in Miracleman #1. Two and a half years later they published a two issue miniseries called Miracleman Family, again reprinting old Marvelman stories from the 1950s, but this time in colour. Issue #1 contains How Dicky Dauntless Became Young Miracleman, Young Miracleman and the Plague, and Miracleman and the Golden Apples, and issue #2 contains The Shadow Stealers, Young Miracleman and the Broken Shoe Mystery, and Miracleman Family and the Hollow Planet. In all cases, these originally appeared in one or other of the L Miller and Son Marvelman titles in the 1950s and early 1960s.

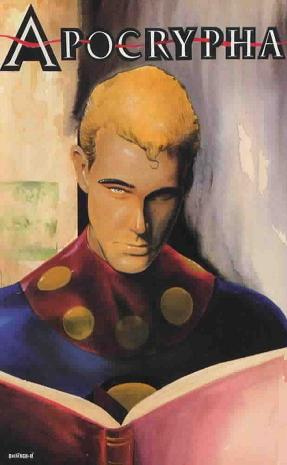

However, despite there being perhaps thousands of pages of these old stories available, Eclipse never bothered to print any more of them beyond the thirteen stories in these titles and in Miracleman #8, presumably because, in the end, nobody was actually interested in them. Whatever charm they might have had in the comics-starved Britain of the nineteen fifties, it had all pretty much worn off by the time they reached a comics-rich America in the nineteen eighties. In fact, there appears never to have been any real interest in reprinting the old Marvelman stories simply for their own sake and, despite having those thousands of pages available to them, neither Quality Communications in the UK nor Eclipse Comics in the US ever bothered to produce a large collection of them, presumably because they knew the market simply wasn’t there for it. Eclipse did produce, between October 1988 and December 1992, three trade paperback editions of Alan Moore’s run on Miracleman; one volume of Gaiman’s run, Miracleman: The Golden Age; and Miracleman: Apocrypha, the anthology title. These five volumes are long since out of print, and change hands for large amounts of money these days.

Bear in mind that Eclipse did not go into an easy bankruptcy. Eclipse’s bankruptcy came about because they had been publishing lot of Japanese comics, which were translated by a guy called Toren Smith. When Toren took the licence away from Eclipse and went to Dark Horse, he suddenly discovered that he was making four or five times as much money! But the sales had not gone up and the deal was pretty much the same. So then he got his accountant or his lawyer to get in touch with Eclipse to say, ‘Please send me all the figures so we can do an audit.’ And Eclipse sent both sets of books, the one with the true figures and the false figures. Given that Toren had the true figures and the false figures, he took them to court and the judgement… it was pretty much an open-and-shut case. There was a $100,000 judgement against Eclipse.

They paid it for one month, they paid it for a second month, but when the third month happened there was no payment forthcoming. Dean and Jan had cleaned out Eclipse and let it close down. I know this from Toren because this was something Toren was telling me at the time. He phoned me up and told me one day, ‘Hey, Jan and Dean have offered me Miracleman in exchange for this $100,000 or whatever, do I take it?’ And I said no, and I said, ‘I’d say no too, given the tangled history of Miracleman.’

Dean Mullaney, in an interview quoted in an undated article on the Poor Mojo Newsletter website called I Always Wondered What Killed Eclipse Comics, had a very different version of events,

The irony of all this is that, in this day and age when graphic novels are regularly reviewed in the mainstream press, the reason Eclipse went under was due to my single-minded desire to establish graphic novels in mainstream bookstores. Eclipse had signed a mutually exclusive contract with HarperCollins to produce graphic novels. The plan was to first introduce titles by authors already known to booksellers – J.R.R. Tolkien, Clive Barker, Dean Koontz, Anne McCaffrey… we even had an original by Doris Lessing in the planning stages.

Unfortunately, HarperCollins didn’t, in my opinion, really understand what graphic novels were all about. And there were internal conflicts at HarperCollins, to which I was never privy, that left Eclipse holding the bag. They had given us an advance to start production, but that money ran out, and we had a full schedule in production. We never received a single royalty statement, let alone check, from HarperCollins’s sales to bookstores. The cash flow deficit eventually forced us to close up shop.

In an interview with Richard J. Arndt quoted in the same article, he says,

I’ve never really told anyone why Eclipse folded. It had nothing to do with cat and I getting divorced. First of all, the comics specialty market was in the toilet. … We were a small, family-run business. So things were incredibly tight. Eclipse didn’t have bankable continuing monthly series. We entered into a co-publishing deal with HarperCollins. … It was an exclusive deal both ways. In the beginning, it was a fantastic relationship. …

The problems started when we asked for sales figures on the other books (Miracleman, Clive Barker’s titles, Dragonflight, Dean Koontz’s Trapped, etc). We never – EVER – received a single sales statement. Therefore, no royalty statements. So there I was, paying advances to creators (bigger than the top rates in the field at the time – hey, we were going to be in bookstores, too!), tying up all my capital. And then nothing from Harper. No statements, no money. Meanwhile, creators were naturally asking for THEIR statements and royalties. I explained the situation, but still never got anything from Harper. It got to the point that I had no cash left to even carry on normal business because we had laid out everything we had for advances.

All that was left to do was sell off every piece of inventory I could get my hands on, pay all the little guys (individual creators and small vendors), and stiff the large ones (printers and freight companies). And declare bankruptcy. I still have no idea how many copies of our graphic novels Harper sold, or what they did with the money owed us and creators. But my plan for placing graphic novels in bookstores was still a good one. I just picked the wrong publisher and was about ten years too early. If Eclipse were around now, there’s no doubt that we would be the leading graphic novel publisher in mainstream bookstores.

There is another, again slightly different, version of events given by catherine yronwode, speaking to George Khoury in Kimota! about allegations that David Campiti, Mike Deodato Jr’s agent, never got a payment from her for Deodato’s work on Miracleman: Triumphant:

What happened at the very end was that Dean essentially abandoned Eclipse when he abandoned me. David Campiti was owed money. There were two bank accounts, one in New York and one here in Forestville, California. I could not sign checks on the New York account, but on the Forestville account, Dean had signature power and so did I. Dean cleared out the Forestville bank account long distance, from New York, and there was no money to pay David Campiti – and I was at the San Diego Convention that year and Dean did not show up. He had run off with his new lover, and I was trying to hold together a booth showcasing twenty-seven new products we had just come out with since he left. In addition to dealing with my husband leaving me after twelve years, this was pretty dramatic for me – because Campiti had been told by Dean to bring artwork and there was no money!

cat yronwode chose a very dramatic way to announce her version of her desertion by Dean Mullaney to the world. As part of a full-page ad for Eclipse Comics in Comic Buyer’s Guide #1034 (September 16, 1993) she had her Fit to Print column, which this time seemed to be one hundred and one lines of some sort of free verse composition. It started like this:

This is Fit to Print number 482:

he promised her a layout table, but

office days and nights

side by side they

erased pages and cleaned up ligatures

When others had forgotten

how it should have been

or typeset and pasted like demons

Rushing to Fed-Ex at closing time

eating Mexican at Joe’s or Fonseca’s

and then at Austin Street or

delaware Street or Lover’s Lane

Collapsing with fatigue and pride

on the rug she imagined the future

damn you he said, so she

erased her mind and cleaned up spilled

Those Who Read Code Can Get The Real News Dean Has Left Me For A Woman Named Jane Kingsbury Who Has Bone Chips In Her Brain – Cat

In a 2005 interview with Richard J. Arndt, Dean Mullaney stated that he was married to Jane Kingsbury, ‘my best friend since Junior High,’ but there was no mention of the bone chips in her brain, which we can only assume may just have been the invention of ms yronwode.

Neil Gaiman gave his own perspective on events, again talking to George Khoury in Kimota! :

The bit that nobody ever knew was that we wouldn’t start writing ‘til we got paid for the last episode. I would stop writing and Mark wouldn’t start drawing. It wasn’t that we were a year late. It was like one day our checks would turn up and then we start working on it because the checks were so amazingly unpredictable from those guys. We didn’t realise at the time that they were being creative with the royalties, all the stuff that ended up sending them into bankruptcy – being essentially closed down by the court. But the thing was that we never knew that it was closed down. No one had the courtesy to say.

I got one phone call from cat yronwode, which was very good, as things crumbled, that Dean was getting weirder and more desperate. What was bizarre about #25 is they used to regularly solicit it. They had the art but I don’t think they had the money to colour it and I don’t think they had the money to print it, either. So it was sitting in a drawer and cat phoned me. I said, ‘Look, I’m getting really concerned given some of the weirder stuff Dean is doing to make money that I will turn around one day and see that Miracleman #25 is appearing in Playboy Comics as a one-shot since none of us are getting paid.’ And she said that this was a valid and serious concern, ‘Would you like the art back?’ and I said, ‘Yes, I would,’ because stuff was disappearing. So cat – good call, bless her heart – she sent us the art back.

Eclipse Comics’ demise began in the summer of 1993 when cat yronwode and Dean Mullaney who, along with Jan Mullaney, owned the majority of Eclipse stock, entered into divorce proceedings. The company subsequently entered into bankruptcy proceedings after being hounded by a variety of creditors, as well as having lost a judgement to Studio Proteus owner Toren Smith. The California Superior Court awarded Smith $122,328 for the translation and packaging of several Japanese books Studio Proteus had done for Eclipse between 1988 and 1992. Eclipse also owed money to the artists who drew Miracleman, according to Neil Gaiman.

Dez Skinn had also had difficulties getting paid by Eclipse, apparently. Whereas he had originally supplied them with photographic material to reproduce the Marvelman strips that had previously been published in Warrior, they later used photocopied pages from their own copies of the magazine, as they didn’t have the money at hand to pay Skinn for his originals. In Kimota! he told George Khoury,

The relationship with Eclipse soured very early on. […] We started withholding material from Eclipse. We just stopped sending the stuff over because they weren’t paying us. […] So what Eclipse did was because we weren’t sending them prints over, they just started making copies from Warrior […] So ultimately to resolve it, I had a meeting with Jan Mullaney – Dean’s brother – in New York, in some really seedy bar. He turned up looking like a real hippie with a couple of thousand dollars in cash in a brown envelope. […] That was when we finally resumed transactions.

Eclipse’s part in the story of Marvelman does not leave them covered in glory, and it seems that in general their business practices were unpleasant and wilfully duplicitous. I don’t think it’s unfair to say that, certainly when it came to Miracleman, Eclipse were saying one thing but doing another – although they’re unlikely to be alone in that, I suppose, particularly in the American comics’ industry. Perhaps the most reprehensible part of their association with Marvelman is the way that Eclipse – those great exponents of creators’ rights – completely ignored Alan Davis’s wishes not to have his work reprinted. Despite all that happened, Dean Mullaney still felt he could write a self-congratulatory article in the back of Total Eclipse #1, where he says, amongst other things,

You could say that Eclipse Comics was formed because I believed that comics’ writers and artists should get a square deal. […] When Eclipse was formed, I made it a point to read the Copyright Act of 1976 and was particularly interested in the section dealing with the ‘work made for hire’ clause that is an essential part of almost every comic book publishing contract […] We vowed that Eclipse would never force a writer or artist to sign such an agreement. And we never have.

One way or another, and whatever the cause – cat blamed Dean, and Dean blamed HarperCollins, but the smart money would have said it was because they were fiddling the books, and one day it all came home to roost – Eclipse had gone bust, and yet another publisher associated with Marvelman was no more. The Bankruptcy Court appointed a representative to dispose of their assets, and an auction of those assets was held in 1996. In the same article in The Comics Journal #185 referred to earlier it says,

The final chapter in the saga of Eclipse Comics came to an end when Image impresario Todd McFarlane purchased the trademarks and character rights, along with two pallets of tangible property, of the defunct comics company at a Stoney Point, New York, auction on February 29th.

McFarlane beat out eight other bidders for all copyrights, trademarks, characters, and other intellectual properties, along with the remaining trading cards, film negatives and publishing agreements held for Eclipse comic books by the court. According to Mary Ellen Lynch, the attorney handling the case for the Bankruptcy Court’s appointed Trustee, McFarlane employee Terry Fitzgerald quickly won the auction with a winning bid of $25,000. She told the Journal she believes Fitzgerald bought everything that remained of Eclipse, but that ‘it will take about a year or so to close out all the details.’

A perusal of the list of items provided by the auctioneer, Henry Leonard & Company, to the bidders reveals that the real property bought by McFarlane includes a slew of trading card sets, as well as film negatives, covers, and copies of Eclipse comics like Velocity, Parts Unknown, Black Terror, Skywolf, Airboy, and of course Miracleman.

The most valuable piece of the purchase may prove to be the United States Patent and Trademark office registration (number 1,447,456) of the highly acclaimed series Miracleman. Also presented to the bidders as part of the auction was the written agreement on trademarks and copyrights for Miracleman between Eclipse publisher Dean Mullaney and Neil Gaiman, executed on April 1, 1989. Exhibit B of that agreement includes the transfer by Alan Moore to Neil Gaiman and Mark Buckingham of his portion of the Miracleman trademark. Within these nine pages of legalese lie fragmentary clues to one of the most debated questions in contemporary comics: who owns the rights to Miracleman?

The agreement between Eclipse and Gaiman called for the writer to script twenty-six pages for eighteen issues, with illustrations done by Buckingham. While the agreement stipulates that Eclipse Comics owns two-thirds and Gaiman and Buckingham jointly own one-third of ‘all the characters in the Stories and all the trademarks in and to the title Miracleman,’ under an attached agreement signed by Alan Moore on March 7, 1989, transferring his one-third ownership, the agreement states that Gaiman and Buckingham ‘will, in their turn, pass on their part of the trademark to their successors on the strip, or failing that, return the trademark to Alan Moore to keep or pass on as he sees fit.’ This agreement, like the one between Gaiman and Eclipse, excludes the characters created by Moore and Garry Leach in Warrior’s Warpsmith. Though Gaiman and Buckingham were granted permission to use them, Moore and Leach retained the trademarks to ‘the Warpsmiths, the Qys and related characters.’

There was another contract, however, that superseded any others. When Dez Skinn and Garry Leach sold Eclipse their rights to Marvelman in February 1986, the contract contained a clause stating that Eclipse could not dispose of their rights in the character to any third party, and were obliged to offer it back to Skinn and Leach. When Neil Gaiman was talking about Miracleman later on he said,

From another source I also got to see the original contract, under which Eclipse had obtained their license to a part share in the Miracleman character, and it was explicit in saying that in case of Eclipse folding, or even substantially changing directors, that Eclipse’s share in the rights to Miracleman would revert.

To be continued…

And for literally years Todd McFarlane openly claimed that he “owned Miracleman” until Neil Gaiman took him to court and Todd had to present the document shown above which proved that he couldn’t legally own any part of Miracleman. What a guy.

Someone should make a movie about cat yronwode and Dean Mullaney’s breakup (as described here). What a melodrama!

A footnote to this from the letter column of Miracleman is an accusation, from cat yronwode IIRC, that Dez Skinn was being duplicitous with money from the series. A letter questioning Eclipse about rumours that artists weren’t getting paid was told that Skinn had claimed to be acting as representative for Mick Austin, who painted a cover for Warrior re-used for the Miracleman 3D Special, had received payment meant for the artists and hadn’t passed it on to the artist. Eclipse responded that when they’d found out they’d made payment directly to Mick and had deducted the balance from further payments to Dez. So the breakdown in relations was clearly there while publication was progressing…

IIRC Skinn disputed yronwode’s allegation in ‘Comics International’ but I don’t have the exact issue number to hand.

Padraig, I’ve gotta say I’ve been following this religiously, and it truly is an outstanding piece of work. Your dedication and knowledgeably, your ineffable style and what have you. This series has rocked my fucking socks and then some.

What do Irishmen know about comics? I’m a countryman of yours and it prides me to see someone as eloquent and comprehensive as yourself skittering out of this landmass.

What I mean to say, acknowledging that this post is indulgent and sycophantic, not to mention irrelevant, I’m aware, reading your stuff for a while that you haven’t previously been in the best of health. I do so hope you’re okay. I think you’ve become important to a lot of people.

*knowledgeability, innit. Spellcheck death toll.

Tom W and Kate: ‘A footnote to this from the letter column of Miracleman is an accusation, from cat yronwode IIRC, that Dez Skinn was being duplicitous with money from the series.’ ‘IIRC Skinn disputed yronwode’s allegation in ‘Comics International’ but I don’t have the exact issue number to hand.’

Yes, I’m familiar with that particular accusation of cat’s, and Dez’s refutation of same. I decided not to bother with it as I’m honestly not inclined to think that any accusation originating from inside Eclipse has any real worth. They were happy to harass people, and to falsify their accounts and, frankly, that piece by yronwode about her now-ex husband is not the product of a wholly rational mind. And I’ve met Dez, and like him. I doubt the same would ever be true of cat or Dean.

Chalice: Thank you.

another excellent installment. i feel like the drama is definitely kicking in, whereas before was fascinating history about the character and comic book, now we’ve got a full fledged soap opera on our hands.

looking forward next week. the Eclipse owned 2/3 of the character copyright does seem to be the crux of the current state of things.

Slightly, but only slightly off-topic, this installment really makes me want to see a series about the deaths of various comic companies over the years– First, Mirage, Charlton. It would make for fascinating reading.

And here’s James Van Hise to give away the twist ending. It was his sled!

Joe Gualtieri: ‘…this installment really makes me want to see a series about the deaths of various comic companies over the years– First, Mirage, Charlton.’

Funnily enough, that’s pretty much exactly what I think I want to write next. something about the ‘ground-level’ comics companies of the 1980s. I’ve already started mapping out a time-line for it.

Padraig,

The San Diego Reader ran an article in 2008 about the fall of Pacific Comics. Although all the images that accompanied the article are now gone, the text is still there. It can be found here:

http://www.sandiegoreader.com/weblogs/bands/2008/apr/21/pacific-comics-the-inside-story-plus-indie-comic-h/

(Personally speaking, I loved the direct comics scene of the early eighties. You had Eclipse Comics, Pacific Comics, First Comics, Capital Comics, Comico, Kitchen Sink Press, and Catalan Communications. Great times.)

Ooo, the Wayback Machine still has the version with the images. You can grab it here:

http://web.archive.org/web/20080501144000/http://www.sandiegoreader.com/weblogs/bands/2008/apr/21/pacific-comics-the-inside-story-plus-indie-comic-h/

Padraig,

I just wanted to say that I am really enjoying this series each week. It is an absolutely fascinating piece of comic book history…Could it be the first foresnic true-life comic book procedural? So far, we have heroes, villains, treachery, deceit and moral ambiguity. If we could get a sword fight and some monkeys fighting robots it would be perfect.

But seriously, I really do hope that you can get this published some day as I want to buy a copy.

Hi, all — Padraig O Mealoid, please correct yourself. What i actually stated (and what you actually quoted) was that Dean Mullaney cleaned out the Forestville bank account, leaving me no money to pay David Campitti at the San Diego convention. How you leaped from that statement to your opinion that i was “blaming Dean” for the company’s financial problems is beyond me. For all i know, his assessment of the Harper-Collins aspect of his company’s financial woes may have been accurate, but i would not have been able to judge that, because, as i explained, i was not privy to the company’s financial dealings and i had no access to the company’s main (New York City) bank account. As for the bone chips, which you assume i fabricated, no less a person than Dean Mullaney told me about them. The bone chips were the inoperable result of a traffic accident his lover (later his wife) had been involved in. He told me this during the long distance telephone conversation in which he declared his love for her and also informed me that our marriage and my previous employment were being unilaterally terminated. Although i am sure her medical condition was distressing, i must admit that Dean’s phrase “she has bone chips in her brain” was so anomalous and sounded so funny to me that it became a sort of mantra by which i reminded myself that, no matter how financially terrifying the collapse of Eclipse seemed at the time, Art Linkletter had spoken truly when he titled a popular segment of his TV show, plus a couple of cute books, “Kids Say the Darndest Things.” No offense intended to the living or the dead, but “bone chips in her brain” was one of those “darndest things” — a spectacular oddity of speech that one would hardly expect to hear while being informed that one is being dumped, divorced, and losing one’s job. In fact, twenty years later, just reading the phrase, “She has bone chips in her brain” still brings a smile to my face. http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/a/af/Kids-say-darndest-things.jpg

To continue this, in terms of finances … Again, i was not privy to Eclipse’s financial dealings, but the lawsuit Toren Smith brought against Jan and Dean Mullaney certainly would have hit them hard financially. By the way, you have provided no date for this “$100,000” (per Gaiman) or “$122,.000” (per The Comics Journal) California Superior Court judgement — and a cursory Google search has failed to turn it up, either. Toren is dead now and cannot comment, but you quoted Neil Gaiman (an outsider to the situation) stating hearsay that Jan and Dean were paying Toren off in monthly installments, until something happened to stop them. Now, Dean has directly stated that he was owed money by Harper-Collins (“I still have no idea how many copies of our graphic novels Harper sold, or what they did with the money owed us and creators”), and that might explain his company’s failure to continue payments to Toren Smith — except for one thing: Dean and Jan could (and should) have sued Harper-Collins for breach of contract, and apparently they did not. So my next question would be to ask Dean why he and Jan did not sue Harper-Collins for failing to produce sales records and royalty statements.

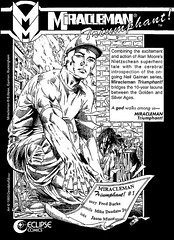

How odd that Neil Gaiman “claims to have no knowledge” of the “Miracleman Triumphant” mini-series by Fred Burke and Mike Deodato, Jr. I certainly recall our having an editorial discussion by phone about this proposed “continuity implant” and i recall us working out a storyline that would not interfere with anything he had planned. Shortly thereafter, Fred, Mike, and i were given the go-ahead by Jan and Dean to start the work. Later, when Eclipse was falling apart, i called Gaiman, among other creators, to arrange the return of material (which he has acknowledged that i did) — and at that time i asked him what he wanted me to do about the “Miracleman Triumphant” art, as i figured he was somehow a co-owner of it, and might find a new publisher for the series. He told me that he didn’t want it sent to him as he had not directly worked on it. So i didn’t send it to him. He certainly knew it existed, even though he has forgotten it now.

Padraig — This is regarding the Mick Austin art which Dez Skinn showed and sold to Eclipse in the form of a large colour slide — and which, due to the subject matter, i i was sure was art originally commissioned for a British model-building hobby magazine. The meeting we had with Skinn in New York at a bar near the UN headquarters, his mid-day sousing as we sat in a darkened booth, and his showing us the C-prints for painted covers for which he claimed he had the rights was all so strangely non-business-like that it made a vivid impression on me. I remember Dean’s decision to use the Austin art on the cover of a science fiction anthology by requesting a writer to craft a story to fit it. I recall the upset at the office that ensued when Dean told us that Skinn had not paid Austin. While composing a lettercol, i was instructed to write (and i trusted it to be true) that the Mullaney brothers had paid the fee for the art to Skinn, as Austin’s supposed art agent, and that a second fee was then to be paid to Austin, since Skinn had never paid Austin. Skinn has made a “refutation” of this account, according to you, but although he has denied it, he has also never presented evidence that he paid Mick Austin. You choose to believe Skinn because, in your own words, you “like” him. Your editorial decision, like mine of many years ago, leaves us with several serious questions: Since the Mullaney brothers and Skinn were in disagreement on the issue, does anyone know what Mick Austin has said, or what his friends and family have known of this event? Has there ever been any evidentiary corroboration of Skinn’s version of events? Of the Mullaney brothers’ version of events? I faithfully reported what i was told — but if there is evidence to the contrary, and i was used as a tool, i would certainly like to know it, even at this late date.

Having read all of these, and the latest of Cat’s insight…what comes to mind from purely as a fan is “Jesus, what a train-wreck”. I loved what Eclipse did, along with First, and Comico, but are some things that went down that makes me sad to be a human.

Years ago, while working as a Bailiff/Deputy Clerk in a Probate Court I encountered a case where folks were fighting over ownership in various race horses. 1/32, 1/64th, etc. I saw a fist fight break out over it. These horses were not even champions, and no one in the fight was hurting for cash.

At the time, I thought it was a modern “Jaundice vs. Jaundice”. I think the saga of Marvelman may be closer to Dickens than the horse case.

Comments are closed.