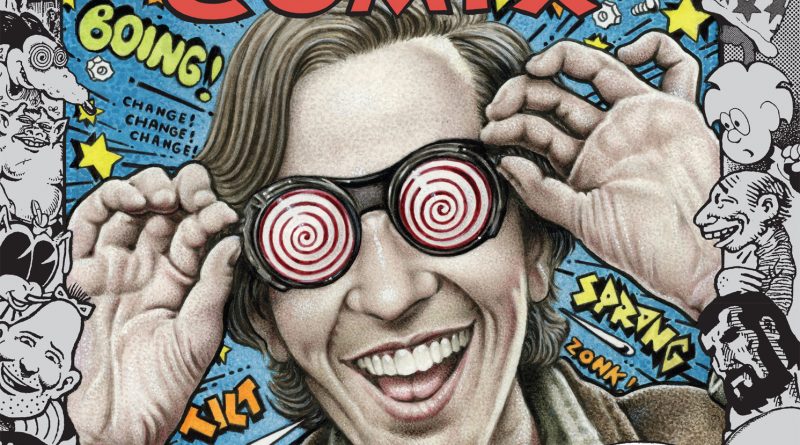

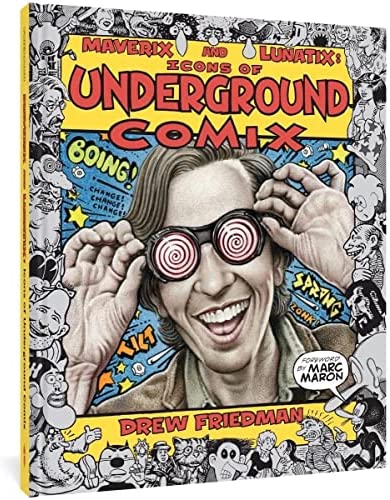

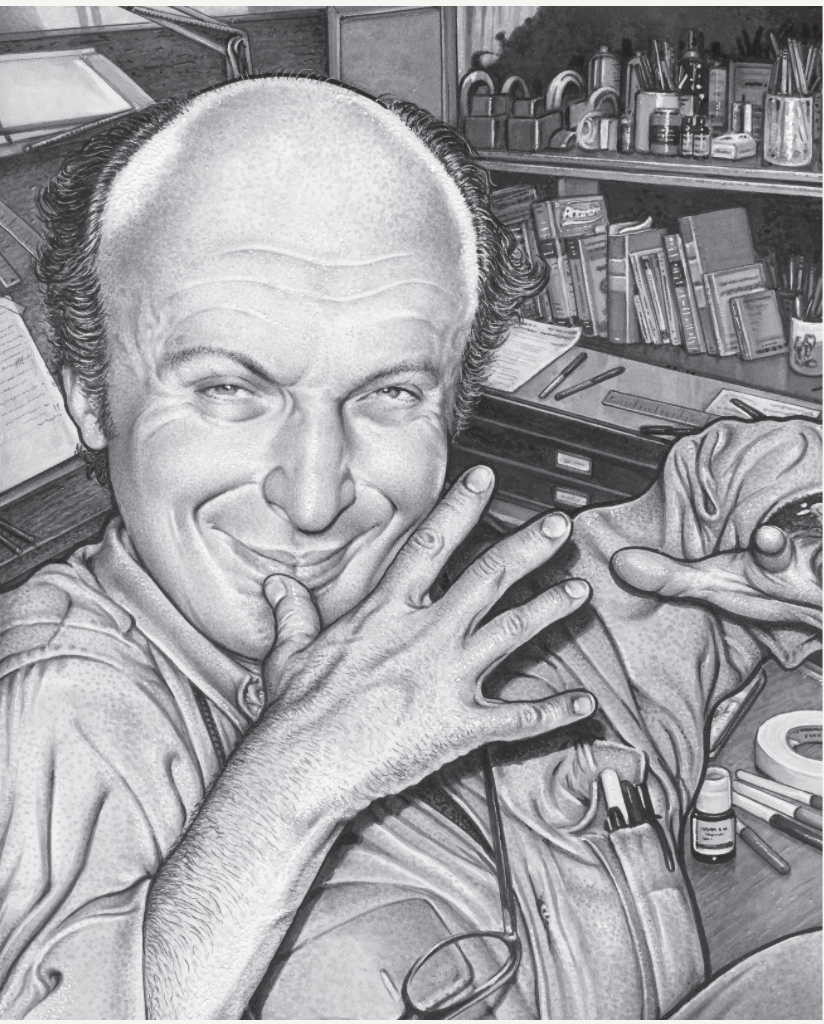

After tackling a solemn book rendering the Presidents of the United States, Drew Friedman returns to a familiar milieu with his new Fantagraphics book, Maverix and Lunatix: Icons of Underground Comix. With his unique hybrid of expressionist, hyper realistic/pointillistic, yet still cartoony portraiture, Friedman presents an illustrious group leading the vanguard of the alt-comics movement in all of their raw glory. These depictions–homely, haunting, and tragicomic–show the human ingenuity that redefined what comics could achieve. With warmth and a deep reverence for the historical importance of his subjects, Friedman turns his gaze to highlight the famous and not-so-famous names who reenergized comics and widened its potential considerably.

With the release of the new book, I asked Drew about how he determined who was included in the final cut, whether underground is the best description for the movement, and which portrait ended up being the most surprising.

AJ FROST: Hi Drew! Thank you for taking the time to chat with me about your latest book, Maverix and Lunatix: Icons of Underground Comix. I wanted to start by asking you what the term “underground” means to you. Do you think it captures the spirit of the movement? In other words, do you think “underground” is simply slick marketing term, or does it mean something more?

DREW FRIEDMAN: Nice to chat with you again AJ. They were dubbed underground comix by… um, I actually don’t really know… maybe by someone in the media who started picking up on them early on. My understanding is that the term was riffing on underground films that had gained popularity in the mid-sixties by filmmakers like Ken Jacobs, the Kuchar brothers, and others, so I suppose it was a handy label to slap on them.

I think at first referring to them as underground comix made more sense, when Zap landed it was published on the fly, under the radar, and it might have crossed the publishers minds that these naughty, adults-only comics could lead to potential trouble for the artists and publishers, even the possibility of getting arrested and going to jail. I think underground was also catchy and, to me, has a slightly undetectable, illegal, dangerous vibe to it that probably also appealed to the counterculture of the day: “Underground comix are not our parents comics!” “Underground” just stuck, even, well, after the comics went overground.

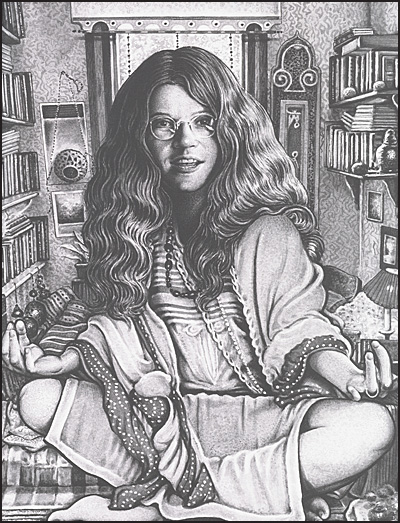

FROST: Included in the book are marquee names like Art Spiegelman, Trina Robbins, Harveys Kurtzman and Pekar, and, of course, R. Crumb. How did you balance highlighting the well-known figures from those who are more obscure? What was the criteria that you used to ensure that certain artists weren’t left out of the final product?

FRIEDMAN: I wanted to create a balance of the celebrated, the not-so-celebrated, and the forgotten. But, to my mind, all of these people are worthy of being called Icons of Underground Comix, based on the quality of their work and their input in the underground comix movement. I knew I wanted to create 100 portraits (the 101st, Jim Evans, was added at the last minute after I realized he had created more UG work than I had previously thought).

Jay Kennedy’s book The Underground Comix Price Guide was an excellent source because it listed every single artist who drew for UG comix; over three thousand. Aside from the obvious choices including everyone you mentioned, I was able to cross reference and discover artists who I was previously unaware of who either contributed to numerous titles, or was a superior but perhaps neglected artist. Or both. A few subjects who I included whose work I was either vaguely familiar with or completely unaware of include Nancy Burton, aka Panzika, George “Hak” Vogrin, Harry Driggs, and Ed Watson.

FROST: Who do you feel was the most challenging cartoonist to render? And who was the most natural?

FRIEDMAN: Getting good reference photos–mainly good head shots–is really important to me. In some cases that proved difficult, or nearly impossible. Aside from imposing on the still living subjects themselves, or their family members, which I’m always uncomfortable doing, tracking down photos of many of the artists was an uphill battle because so many just did their thing anonymously and were rarely photographed. I could only come up with a single photo of Harry Driggs for instance.

In some cases nothing existed, in print or online. That was the case with an artist named Bucklee Bell, who signed his work with the memorable nom de plume Buckwheat Florida Jr. He didn’t do much work for the undergrounds, but his 1969 psychedelic solo comic titled SUDS, published by the Print Mint, had a big influence on R. Crumb, so I felt he needed to be included. My friend, John Wendler, who has an amazing knack for unearthing rare photos and information, was finally able to come up with some blurry snapshots of Bell, one of which worked for just how I imagined depicting him in the book. So, he was set.

Andy Martin was another artist who I felt it was important to include. While still attending college he did something really interesting: George Gross inspired comics and drawings for the late sixties comix tabloid Yellow Dog before he graduated and switched gears. I broke my rule and got in contact with his daughter who happily sent me some pics of her late father. If anybody in the book does not look like an underground cartoonist, it’s Andy Martin!

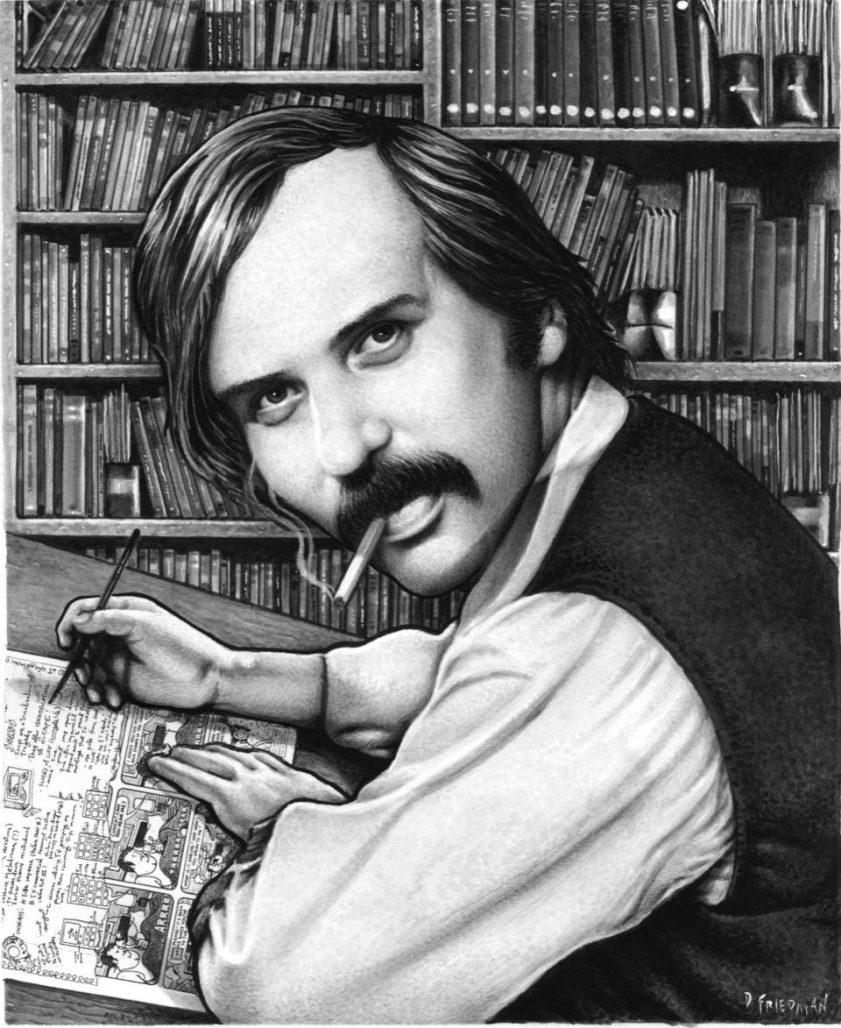

The most natural was probably the portrait of R. Crumb.

FROST: Over the course of creating the portraits for this book, what surprised you the most? Did your perception about any of the artists you included in here change? Or did you enter and leave the project with your attitude towards certain artists relatively balanced?

FRIEDMAN: I did go into this project with some preconceived notions about which artists I loved, liked, was indifferent to or flat out disliked. My original main reservation about committing to doing this book was that I didn’t love the work of all of the most popular artists who drew for underground comix. I had lunch in New York with Robert Crumb in early 2019 when The Book of Weirdo was about to come out and mentioned my dilemma to him. His response was “So what? You don’t have to like everyone you draw.” Which of course made total sense. That’s when I committed to doing the portraits.

During the two years-plus process of creating these images, I’d also spend about an hour a day revisiting my fairly large and yellowing UG comix collection for inspiration; also myUG anthologies. I took a second or third look at many of the artists who I had previously not cared for and discovered a deftness and quality in their work which I hadn’t previously noticed. In some cases, I was pretty knocked out. The late Richard Corben for example, I had always been indifferent to his work, but now I’m pretty blown away by his drawing abilities and technical skills. Also Rand Holmes, Greg Irons and Dave Sheridan, and quite a few others.

FROST: I found that there is a heavy psychological subtext within your portraits for this book. The artists are usually staring back at the reader/viewer, inviting them into this mini-universe. Would you say that there was an intensity to these artists that was not found among the major comics publishers at the time?

FRIEDMAN: I think that’s true. There was a mini-universe consisting of factions of underground cartoonists–a brief, egalitarian artistic movement–but I don’t think of it as a community or family of artists… although there was a spirit of camaraderie. They were mostly spread out across the country, mainly in San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, Texas, Wisconsin, and Chicago. But what they all shared in common was the isolation of being a lone artist at their drawing table.

Crumb enjoyed his celebrity, at least at the beginning, but I always sensed that aside from traveling, the women, playing live music, what he most wanted to be doing was sitting at home drawing comics. I think that also applied to most of the mainstream creators: working alone, for not much money, in some cases at shabby wooden desks in their basements, like Jack Kirby, not a flamboyant or sexy lifestyle at all. I wanted to try to capture that in many of the portraits: artists alone but briefly looking up and connecting to the outside world to the reader.

FROST: I asked you this during our last interview, but which portrait included in the book surprised you the most? And why? Or, were there no surprises because of your familiarity with the material?

FRIEDMAN: Well, I suppose being surprised for me was discovering artists whose work I was previously unfamiliar with. I think the most pleasantly surprising and unexpected portrait for me to render was Harry Driggs… if ever there was a face made for me to draw! A friend mentioned that he looks like he could be a Manson family member. I responded that he could be Manson himself!

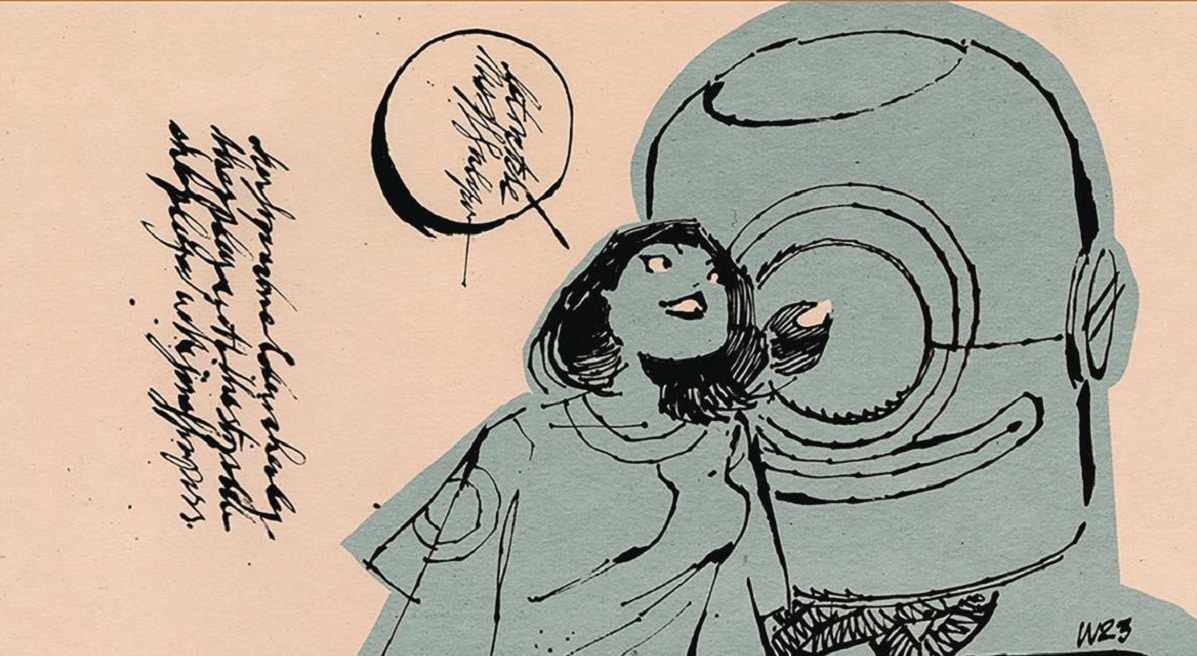

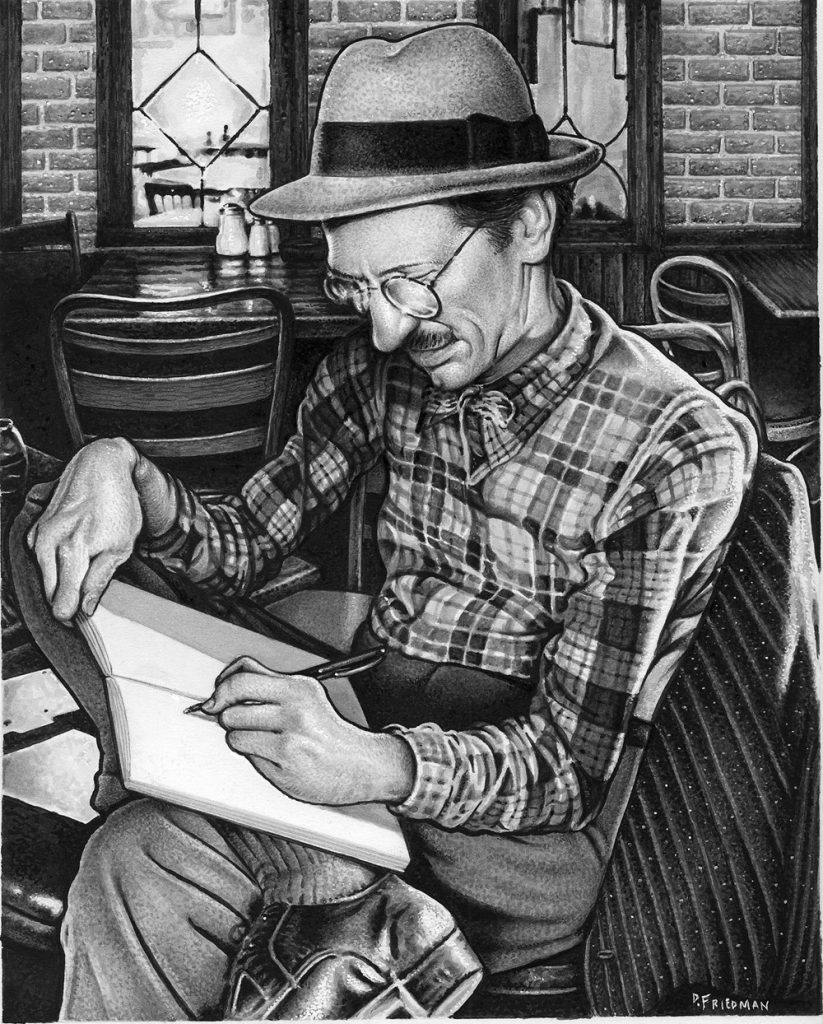

FROST: Your portrait of R. Crumb has him delicately cradling a blank sketchbook with his pen only millimeters from the page. In your mind, what is he about to create on that blank page?

FRIEDMAN: I knew I didn’t want to draw Crumb in any way heroically, or even, like on the book’s cover, happily connecting to the viewer. Rather, Crumb in solitude, alone in a cafe, circa mid-seventies, looking downward, doing what you would expect, drawing, or about to draw since the sketchbook pages are blank. I toyed with including some of his drawings in the sketchbook. But, finally, I felt it would be more interesting to leave the pages blank, to let the viewer speculate about what he might be about to draw.

FROST: What are you working on currently and when can readers expect to see your next project?

FRIEDMAN: I’ve been referring to this book of UG portraits as my pandemic book, or, how I spent my time during the pandemic. But during that dark time I also took on some assignments and commissions, and created new portraits as limited edition prints. I’ve assembled close to a hundred new pieces, many of them portraits, so they’ll all be collected into a new book which will be titled Schtick Figures. It should be out by later next year. My late pal Gilbert Gottfried is going to be the cover boy.

FROST: Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me.

FRIEDMAN: Thanks AJ. Always great to talk to you.

Maverix and Lunatix: Icons of Underground Comix is available now from Fantagraphics and other fine (and maybe not fine) retail establishments. You can read more about Drew Friedman on his website, Facebook, or purchase art here.