(WARNING: Spoilers ahead, including the big reveal.)

Whenever a movie claims to be the new vision of anything, or the next evolution of something, the mind starts to fill in blanks no one ever said were there to be filled in to begin with. Some of this mentality came along with the release of James Wan’s Malignant, a Giallo-inspired horror movie that was heavily promoted as “a new vision” of horror from the director of The Conjuring.

Expectations were high and the ad-campaign’s insistence on preventing spoilers to safeguard the movie’s secrets all helped ramp up the anticipation (much like it did when Alfred Hitchcock pleaded with audiences for the same thing when Psycho was about to be released in 1960). Of course, Wan added to the hype by stating in an interview with horror website Blood Disgusting that “I’ve always harbored this desire to make a Giallo movie, but do it my way; my version of Giallo.”

So, the question now is, did Malignant fulfill its new horror promise, this new version of Giallo, or did it oversell the expectation? The answer lies in that pesky ‘Yes and No’ area, but what it undoubtedly does deliver is an ultra-inventive approach to Giallo horror and monster creation that is fresh enough to warrant attention.

For those who haven’t seen the movie yet and don’t mind spoilers (or saw it a while ago and don’t remember it all too well), Malignant centers on Madison Mitchell, a woman carrying deep traumas from a hazy past, who’s suffering from visions of real murders authored by a dark figure in a long black trench coat. The killer sports black gloves, long black hair covering its face, and an obscene bladed weapon that screams bloody murder every single second it’s on screen.

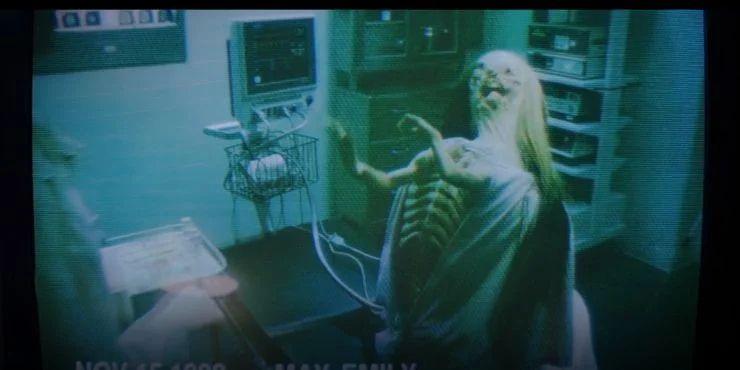

The killer is revealed to be a parasitic twin called Gabriel that was once thought to be excised from Madison’s body, but that is actually still living inside of her, almost like a dormant tumor waiting for the perfect moment to come back and claim the life that was robbed of him.

His disfigured face comes out through a slit in the back of Madison’s skull and takes over her body by contorting it and bending its limbs backward. This makes Gabriel move in a deeply unsettling way, torturing Madison’s body in the process as punishment for keeping him a prisoner inside her head. Gabriel wears the black trench coat mentioned earlier backwards once he’s in control of the body. It’s how he claims the body for his own, attempting to remake it in his distorted image.

This approach to monster creation plays with a theme that tends to accompany ‘Jekyll & Hyde’-type characters quite often: transformations in personality also manifest physically. The monster is portrayed as an aggressive and angry being that won’t settle for anything less than a hostile takeover of the body, keeping us aware that the story’s villain is not going to end up being a disturbed human being acting out against his or her repressed ideas by murdering innocent people. In the process, Wan might’ve given the horror world a new monster worthy of several sequels or even its own universe (which is what many filmmakers and studios tend to aim for nowadays).

At a surface level, Italian Giallo fans will feel right at home with Malignant. The neon-lit kill sequences, the ultra-violence, the twist-filled killer mystery, and the ridiculously bizarre plot developments (which err on the side of the non-sensical in most cases) all stick close to the traditions established by the titans of Giallo filmmaking, with Dario Argento, Lucio Fulci, and Mario Bava among their biggest names (if not the top three).

And yet, these Giallo elements seem to be set firmly in place to offer support for when Wan decides to push them to their breaking point, and beyond, in order to explore other ideas the Italian slasher genre should’ve allowed itself to indulge in years ago.

Unlike some of the Giallo films referenced in Malignant, like Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970) and Tenebrae (1982), Wan’s story has a more logical sequence of events leading up to the reveal, featuring clear exposition bits that make sure everyone knows just who the killer is and what drives his death-dealing ways. One thing this movie isn’t is convoluted, something that can’t be said of even the most celebrated examples of the genre.

Argento’s Giallo classic Deep Red (1975) comes to mind here, as an example of what Wan tries not to do with his film. In Deep Red, the gruesome murder of a psychic medium leads to a hunt for her killer led by the musician that first found the body. Once it all starts, the events leading up to the reveal of the killer’s identity are presented as an attack on the senses (featuring a hypnotic score by the band Goblin) that imbues everything with a kind of dream logic where events are more loosely connected than is usually the case in traditional horror thrillers.

There’s an intentional aspiration to ambiguity in Deep Red driven by uncomfortable camera angles and dynamic zooms that keep viewers in unsteady narrative ground, but it’s at the cost of coherent storytelling. As is the case in most Giallos, the killer remains hidden all the way to the end, viewers having only seen him or her faintly silhouetted in the background or from the killer’s own point of view, black-gloved hand slowly moving towards victims with a sharp knife at the ready for stabbing. Sometimes, the killer’s silhouette bears a shape that doesn’t even accurately represent that of the person responsible for all the blood and gore.

Wan changes up the formula considerably here by choosing to reveal the killer’s identity and origin about halfway through the story. By mixing up expectations, he opens the door for new forms of violence to be explored in the service of extracting terror from other vantage points. In essence, Malignant wants to avoid being just another Giallo or a mere homage to it. This is where Wan’s vision goes into uncharted territory.

Perhaps one of Wan’s biggest departures from classic Giallo comes in the distance he puts between the camera and the killer. Malignant sees Wan pull the camera back to let audiences try and make out the nature and method of his killer, something classic Giallo abhors (as stated earlier). We can appreciate Gabriel’s strange body language, how wrong it looks, and how intrusive his takeover really is.

Early on, one can easily come up with a supernatural or demonic explanation behind the film’s core mysteries. There’s a lot of guess work still, but there’s more to pull from on a visual level by letting Gabriel be seen more clearly before the movie pulls the veil back entirely. It gives audiences more to play with instead of a weirdly shaped shadow or an ominous killer hand chasing soon-to-be-dead people.

In a curious twist of fate, with these alterations to the formula—making the story less convoluted than those found in its influences, pulling the camera back on the killer, and being more generous in its revelations—Malignant ends up being a more accessible variant of Giallo that’s more inviting than the classics it references. That in itself is an admirable achievement.

James Wan’s intention with Malignant is to broaden the scope of Giallo filmmaking by taking the genre into places it hadn’t yet dared go to. The influences are present, but so to is the desire to not settle. Maybe the result could give rise to a new kind of Giallo to grow in, a neo-Giallo subgenre, if you will. In any case, Wan does leave us with an important lesson on horror filmmaking: what’s come before is never truly bled dry of possibility. The potential for fresh stories is always there, be it heavily influenced or not.

What’s old can be new again if we approach it with a mind to take it places it hasn’t gone to before. Malignant certainly champions that, and while it doesn’t create something entirely different, it certainly opens up the floor for old haunts to find new ways to spread terror.