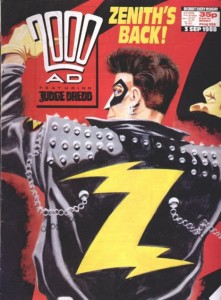

Once upon a time there was a comic strip named Zenith. The creators created, the publishers published, but not a contract was there to be found. 21 years later, Rebellion are going to the printers – but who owns what?

The Preamble

In light of our hard-working Pádraig Ó Méalóid taking a well deserved break, and somewhat of a resurgence of interest in the hero known as Zenith, I present to you a new mini-series exploring the history of that infamous strip: Zenith. With a newly announced reprint seemingly en route, and a legal dispute not quite behind us, I therefore also need to slap a bunch of disclaimers across the beginning: that this in no way speculates on who is right and who is wrong, and that it seeks only to bring you the facts, histories and quotes at my disposal in order to better allow all readers to form their own opinions and judgements. And as with any piece on UK comics history, a certain Mr Moore does of course make an appearance or two…

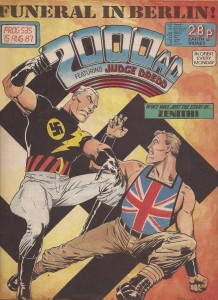

In a post-Watchmen world, Zenith was the punk-ass little brother with a different take on the new-found realism of superheroes; the average person on the street would become not an atomic god, impotent geek or a radical fanatic, but a shallow, brattish celebrity. Had reality television existed in the 80s, Robert Neal Cassady McDowell would have been slurping his cat milk and wanking under the duvet with the best of them before striving to bag a Kardashian. As it was, he became a manufactured pop star, bedding Page 3 girls and flying – quite literally – home drunk. The strip is scarily prescient in far more subtle ways, but we’ll save that for a later instalment.

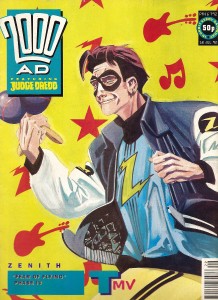

If it all sounds a bit dark and gritty nonetheless, let’s back up a little. Zenith was created by Grant Morrison and Steve Yeowell – with a helping hand from Brendan McCarthy – for the UK readers of 2000 AD, a rebellious little home-brewed comic best known for the adventures of the darkly brilliant Judge Dredd. These pages were not the home of spandex-clad fisticuffs, but of sci-fi epics and twisty wee tales, all presented weekly in anthology format. A superhero strip here then was something rather new, but the more cynical edge to proceedings in comparison to their super-duper American cousins meant that non-heroic protagonists were quite acceptable at all times.

Zenith was a knowing nod to the selfish and self-serving morals being encouraged under our Thatcher-led Conservative government – a dark time indeed for those beneath the middle classes, yet incredibly fruitful in the world of art, literature and music as creators fought to communicate their counter-messages to the world. Punk rock, alt comedy, a move towards creator ownership in comics – the peasants were indeed revolting.

Zenith was also a celebration of UK comics history, and a cheeky look at pop culture in general. The left-leaning 2000 AD was a perfect fit for this fun yet shallow superman.

I’ll take this early moment to note as well that all art appearing in this series – unless otherwise stated – is credited to Steve Yeowell.

The Case

Despite some initial collections from Titan, further reprints of Zenith have been blocked for years due to a dispute over ownership of Zenith as a property. 2000 AD maintain that they own the rights while Grant Morrison contends that they do not have the paperwork to prove that. This is not an argument that Morrison had at the time of initial publication, rather one he put forward in later years in greater understanding of the situation, so early interviews with the writer at the time are not entirely illuminating. There are however other pieces of the jigsaw that help build a larger picture.

2000 AD maintain that they have never sought creator owned work and the implication was always that comics were created on a work for hire basis. However, they also operated without contracts in many cases before the early ’90s, and under UK law a creation belongs to the creator until the rights are signed away – regardless of publication or payment.

As we all know, particularly from Pádraig Ó Méalóid’s series on the convoluted history of the rights battle for Marvelman, Poisoned Chalice, here on The Beat, the issue of creator rights versus lack of paperwork is a tricky business indeed, both ethically and legally. (In fact our research here keeps crossing paths!)

Morrison is also known for his seemingly unsympathetic outlook towards those in the past who have signed away their rights for a pittance in the world of comics, eg Superman’s Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. However, this is a bit of a misconception: Morrison’s stance is that of pragmatism that he does sympathise but that it is not his battle. Frustration at being expected to make a personal stand or even stop writing Superman himself has shadowed him for a few years now, so hopefully it won’t take over the comments here too!

It’s also worth bearing in mind that the persona Morrison was using at the time (late ’80s/early ’90s) was basically that of Morrisey – a slap happy upstart that slags off the world and hogs the spotlight. His Drivel column in Speakeasy magazine is a notorious example of the style that Morrison says in Supergods makes his “blood run cold these days.” It’s a regret he expressed much earlier in the Speakeasy issue immediately following his last column, likening being powered by hate to the then immortal Thatcher, when interviewed by a young chap named Warren Ellis:

“I thought that if I encouraged enough people to loathe me, I’d live forever. Eternally young… The idea was writing Drivel, that I’d remain visible… I’m glad it’s over.”

Of course he remained rather outrageous for some years to follow, particularly when teamed up with a certain Mark Millar. It’s something that makes his earlier interviews a little hard to take entirely seriously, as one is never completely sure whether it’s the relatively quiet but enthusiastic Morrison speaking, or the spikey, angry Morrisey-on.

With only the most successful comics creators ever having the financial security to challenge rights issues, it’s easy to forget that there is also an artist involved in all of this: Steve Yeowell, who still works for 2000 AD today. Much of the below focuses on Morrison as it he who has made a stand, but this is in no way mean to erase Yeowell. Unfortunately as we shall see, the publisher has a habit of not hiring back those who challenge for rights, but in the meantime Yeowell has given a couple of interviews, both here at The Beat and over at Multiversity Comics. His statements have been very diplomatic, and I’ll be speaking with him in next weeks instalment.

This then is a collection of the facts – and nothing but the facts – born from my respect and admiration for Grant Morrison, my fondness for 2000 AD, my love of Zenith, and my anxiety around the tricky ethical minefield of creator rights disputes. My biases are, as ever, laid bare for all to see!

Those involved in legal proceedings around Zenith are not at liberty to comment.

The History

First published by the International Publishing Corporation (IPC) in 1977, 2000 AD had faced controversy since birth with both John Wagner and Carlos Ezquerra, the fathers of Dredd himself, walking out in the early days over creative annoyances and lack of decent financial returns. In the 70s, like many comics around the world, creator credits were not included and the now famous “credit cards” that adorn the 2000 AD title pages were smuggled in courtesy of one Kevin O’Neill, best known now perhaps for his collaborations with Alan Moore.

As Gosnell states in David Bishop’s marvelous history of 2000 AD, Thrill-Power Overload:

“As a trade unionist, I felt immensely uncomfortable with the fact that you sold all rights to IPC. You had to sign your rights away on the back of the cheque – that was totally against NUJ rules. I tried like fuck to get the policy changed.”

In 1981 trouble brewed again when Titan secured the rights from IPC to republish 2000 AD strips in collected editions. The anger here wasn’t directed at Titan, but rather at IPC for not sharing the royalties it received from the reprints with its own creators. Happily Titan proceeded to pay those creators themselves out of their own profits, which still did not make IPC very happy, because, well… awkward.

In 1984, Robin Smith succeeded in getting original art back to the creators for the first time but IPC insisted that creators had to pay to provide copies for IPC to keep. Hrrm. As Sanders admits to Bishop in Thrill-Power Overload, the company could not afford to pay royalties on reprints – so reprints amounted to essentially free profit for the company, whether that be in collections, annuals or whatever was deemed desirable.

Enter Moore

From 1984-86, Alan Moore and Ian Gibson’s The Ballad of Halo Jones was printed in 2000 AD. The strip remains one of my favourite sci-fi series, and indeed one of my favourite Moore works. Originally planned as a nine book series, the strip was ended after just three with Moore initially open about plans to return as stated in his introduction to the Titan collection of The Ballad of Halo Jones Book III in August 1986:

“While there are currently no plans to continue the series, due to external circumstances and considerations, I think it’s fair to say that, were these circumstances to alter, both Ian and myself would be only too pleased to resume The Ballad and continue to relate the history of a character to whom we’ve both grown very attached over the couple of years that we’ve worked with her.”

These circumstances and considerations were of course the issue of creator rights, a frequent plague upon Moore. Speaking to Mustard magazine in 2006, Moore says:

“I got to the point where I’d said to IPC, ‘Look, you know that you’ve ripped these characters off from us. If you were to give us the rights back, I would gladly write another three books of Halo Jones. Whereas if you don’t I will never write Halo Jones and you won’t get any money from the character. And they thought, ‘Yeah, let’s hang on to the character forever and you never get any rights to it and never write any again’. So that’s where it is.”

Moore, who had been writing for 2000 AD since 1980 was never to write for the publisher again. Not that he needed to – in the time since, Marvelman, V for Vendetta, The Saga of Swamp Thing and many more were under his belt, not to mention Watchmen which began later that same year. Still, given his fondness for small publishers and UK comics historically, it’s a damn shame that 2000 AD lost the chance to publish more Moore stories in the years after and to come.

Future Shocks was often seen as the proving ground for new writers at 2000 AD, having previously seen such names as Alan Moore and Peter Milligan grace the pages. (1986 also saw Neil Gaiman add his name to those ranks.)

In July 1987, the IPC Youth Group was sold to Robert Maxwell’s Persimmon BPCC Publishing for £6.8 million cash. Maxwell purchased not only the comic division but also the copyrights for all titles and characters published since 1969 (with some exclusions). A new company was formed: Fleetway Publications.

Just one month later, Morrison’s first long-form strip for 2000 AD began: Zenith.

Zenith Begins

Re-shaped from an earlier, darker idea of Morrison’s for a David Lloyd project that didn’t come to pass, Zenith was designed as a very transient strip – distinctly of the moment and to be seen as dated almost immediately. In the early pages Zenith himself crashes through the window of his flat, rip roaringly drunk while a pre-recorded interview of him plays on the television; a discombobulated Zenith blearily wonders how he can be in two places at once before quite possibly puking his guts up.

The previous prologue placed the reader in Berlin 1944, a UK superhuman fighting the brave fight against a Nazi Übermensch before a bomb – The Bomb – is dropped upon them. 43 years later and the Nazis are active underground with grave plans afoot. Flashy plastic present meets conventional comics bad guys… a theme that appears to be surfacing today. And Jonathan Ross is still a known name. So much for transience!

Created with Steve Yeowell, an artist Morrison had worked with previously on Zoids, a number of character designs were provided by Brendan McCarthy. Inspired by the Paradax artist, it’s no coincidence then that Zenith exudes the same stylish tones.

In an interview at UKCAC ‘87 (United Kingdom Comic Art Convention) with John Jackson of Arkensword fanzine, Morrison and Yeowell are asked how “much of Brendan’s ideas are left?” in regard to the drawings that McCarthy had come up with before his solicited Zenith designs:

“Grant: None of his original sketches were used. We just came up with all-new stuff for Zenith and Brendan’s still got all these great characters lying around. I wouldn’t mind doing something with them some day but I don’t think I could afford to buy them off him.

Steve: You designed the Red Dragon, Voltage and Task Force UK uniforms, didn’t you Grant?

Grant: That’s right. Brendan’s very business minded and they offered him 200 pounds to do the designs. Once he’d done 200 pounds worth he just stopped, so I finished off the remaining characters. I don’t have a keen business mind so I didn’t get anything for my contributions.

John: Did you draw them yourself?

Grant: Yes. I started out drawing my own stuff but I got fed up because it takes too long, as you well know. I still do the odd bit of drawing though.

…

John: A lot of Zenith had already been designed for you, so how much input did you have?

Steve: Brendan & Grant did most of the characters and all of the costumes but I designed Siadwel Rhys and Ruby Fox. Eddie MacPhail was mine too. I just ripped him off from the guy in Tutti Frutti. I liked the designs provided, and they saved me time, so it isn’t as if I’m working with something I’m not happy with.”

Do note that no mention of actual signed contracts is made anywhere – that’s not damning in itself of course, but its worth pointing out all the same.

Zenith was to span four books, or phases, with the first three and their various interludes published between 1987-90 and the fourth after a break in 1992. Additionally a one-off follow up, zzzzenith.com, was published in 2000. Between 1988-90, Titan reprinted the strips in 5 collections. Phase IV remains uncollected, as does zzzzenith.com.

In the same interview from Arkensword #23, the issue of the Titan reprints comes up:

“John: Have 2000AD offered you anything else?

Steve: Richard wants me to do pin-ups and a bridging episode between series to help fill in my time, but there’s nothing concrete otherwise – Titan have asked me to do the cover to the Zenith reprint.

Grant: They never told me there was going to be a reprint.

Steve: Now you know. It’s supposed to be out next March, but they want the cover by October, and I don’t know whether I can make it.

Grant: I’m always the last to hear about these things.

Steve: That’s because you’re only the writer.

John: And because it’s 2000AD you won’t get any reprint money.

Steve: Not a sausage. By the way, Grant, they want you to do an introduction.

Grant: That’s okay. I think Titan offer covers and introductions to the creative people so that they get SOMETHING from the reprints.”

In an interview for After-Image #6 in 1988 by Steve Holland, Morrison talks about how the Titan reprints will now carry the names of the Zenith books – names which previously existed but were not seen in the comic: Tygers, The Hollow Land, War in Heaven, and Jerusalem. (NB, only the first book ended up cover-titled as the reprints broke the second and third into two parts each.) Morrison also reveals that he was unhappy with some of the changes made to his Future Shocks stories:

“I had some bad experiences with the Future Shocks, because they would just re-write them and my name’s still on it. Nobody knows that these things have been completely changed and some of them read like Janet & John, with brain damage. A couple of them were altered so much that they were almost… [looks embarrassed] … I was kind of worried that they would do that with Zenith, since it was my first major project for 2000AD; they could have screwed it up horribly and ruined my career. There’s some border line stuff coming up so it will be interesting to see if any of that has been censored. I think I’m getting away with most things and I must admit [editor] Richard Burton’s been pretty supportive and enthusiastic about Zenith from the beginning”

Pádraig Ó Méalóid tells me that this is also a habit mentioned by Alan Moore:

“…in the SSI Journal, where he talks about one of his stories being done completely differently by the artist. The story seems to have eventually been published under the name of RE Wright (rewrite), which looks like a kind of editorial device to remove the writers name, a la Alan Smithee in Hollywood. You can see the interview here: http://glycon.livejournal.com/2709.html”

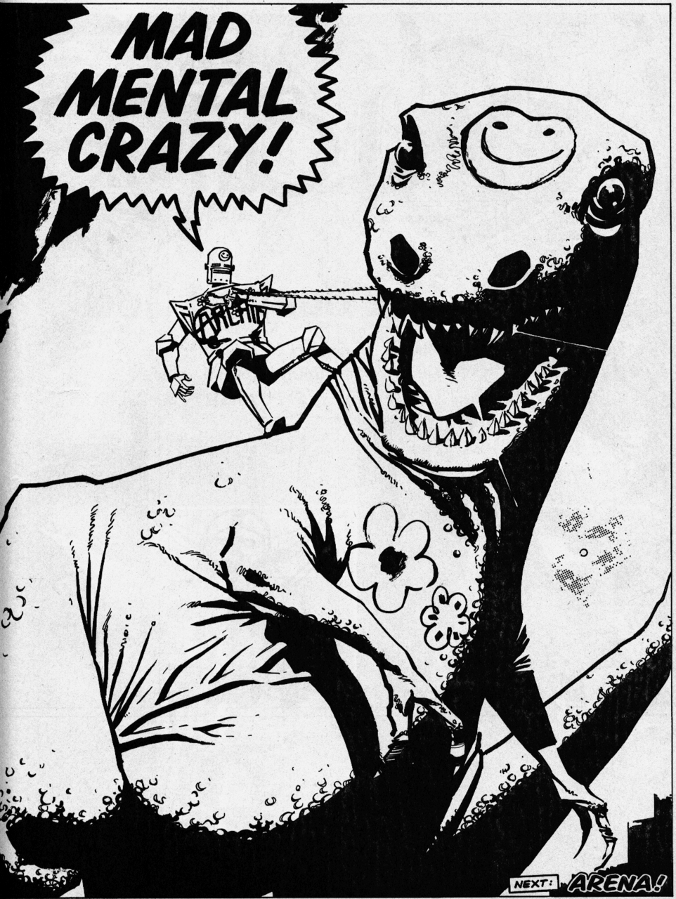

Brendan McCarthy’s original Zenith designs:

(Courtesy of Steven Cook’s Secret Oranges blog.)

Rights, Right?

In the summer 1989, Jon Davidge joined Fleetway Publications as publishing director. Davidge was from the world of book and magazine publishing as opposed to comics, a foreign land where everyone had contracts and royalty payments. With talented individuals now moving to the US for better pay, he set about getting creators their reprint fees, merchandising royalties, syndication benefits and so forth, after John Wagner tackled him about the the amount of Dredd merchandise on the market that he was not seeing a penny in royalties from. Bishop says in Thrill-Power Overload:

“Wagner says the introduction of contract and royalty payments had huge effects. ‘It was such a major leap forward after so many years of creators being cheated.'”

The book goes on to explain that:

“Drafting a suitable document took months The introduction of creator contracts was announced at a party in a Soho vodka bar during the UK Comic Art Convention later that year [September]. At last, material created for 2000 AD would be covered by a written contract that guaranteed writers and artists reprint fees, royalties from merchandising, benefits from syndication and any further exploitation.”

Speakeasy #103 reported on the details in October ’89, explaining that creators would now be paid for the first time on all reprints, graphic novels, publication in the US and Canada, overseas syndication, merchandising, film/tv/video, animation and computer games. The press release stated that the “page rate will in future be a fixed royalty to cover first UK use only.” Asked by Speakeasy to explain the meaning of a “fixed royalty”, a Fleetway spokesperson replied:

“The logistics of paying out a royalty on every copy of 2000 AD sold are beyond all practicality; payment for first use will continue to be the new 2000 AD page rate.”

Speakeasy also reported that:

“Reaction amongst creators was mixed, with regret expressed that no statement was made about copyright ownership, as had been rumoured would occur. The same spokesperson told SPEAKEASY to expect a statement on rights in a month’s time”.

Such a statement does not appear to have been forthcoming, but it’s amusing to note that Speakeasy chose to illustrate the above story with a nice big illustration of Zenith with the caption, “Rights, Right?”.

A feature titled “2000 AD Now” by Stuart Green in the same issue of Speakeasy has the following quote from Davidge:

“We are looking at ways to ensure that de-facto artists have input into the way the character is used, but at the moment we are not looking to hand back the copyright to anybody. However, there is the possibility of looking to say that if we don’t do something in a particularly area, for example, film rights, within a certain period, we give you the right to do it.”

Green also wrote on the issue of “fixed royalties”, stating that Dave Gibbons was “very happy”, Kevin O’Neill wasn’t interested in returning to the publisher without a return on copyright, and that:

“Grant Morrison could only add that “the whole thing sounds very confused, maybe someone will be able to explain it to me in some way”, though he did also point out that he receives a royalty from DC for every copy of Doom Patrol and Animal Man sold in excess of 40,000.”

Signing Those Cheques

If there’s one phrase that keeps coming up in 2000 AD history with respect to creator rights and missing contracts it’s the “you signed the back of the cheque”. Some have stated that creators cashing your cheque was what signed their rights away (untrue), while others have questioned whether the whole idea of no contracts and cheque signing could even be true.

Well yes, it is indeed true. A brief flick through Thrill-Power Overload is enough to confirm this, with Kelvin Gosnell in particular speaking about his unease with the practise. I was still at a bit of a loss as to how such a process could actually work. Fortunately Pat Mills and Steve MacManus were happy to take the time to explain things further for me.

Pat Mills tells me:

“Yes – we did have to sign the backs of the cheques on all IPC Juveniles (Battle, Action, 2000AD, Misty, Tammy, Whizzer and Chips etc). Otherwise the cheque would not be accepted by the bank. Think it had an “R” on it. Later in the 70s, they backed this up further , requiring us to sign a separate docket as well. Later, in Maxwell era (probably Davidge) it was replaced by something else – possibly a work for hire contract.

It led to some interesting and sometimes furious rights battles over the years which are not yet over!”

It has indeed! And we’ll be looking into some of those next week… The Maxwell era began in 1987 but as we can see from the magazine coverage, it did take some time for changes to come into effect. Another 2000 AD alumnus told me that this cheque/docket system was continued until the early ’90s. We know that Davidge joined in 1989 and began getting everyone their reprint fees and that “fixed royalty”. Zenith of course began in 1987.

When MacManus began Crisis in 1988, he did so on the condition that the contributors would have contracts that allowed for royalties and re-use scenarios such as syndication, reprint, collected editions, etc. That contract was created by MacManus himself, and the essence of it became the building blocks for the larger contract that was introduced by Jon Davidge for contributors to 2000 AD, The Megazine and Revolver.

We can see then that a cheque and docket system was definitely used, check boxes and all, and creators would certainly assume that their rights would be being signed over. But is a docket the same as a contract? Contracts were later introduced, and both Crisis and Revolver operated very differently from the outset as we shall see next week.

To Be Continued

In Part 2 next week we’ll look at the other creators who have challenged for or recovered their rights, and how or if their cases differed; all the fun and games of UK copyright law; just who bought what and when; and of course, the curious case of Robot Archie and his IPC chums.

Special thanks to:

David Bishop

Steve MacManus

Pádraig Ó Méalóid

Pat Mills

Mike Molcher

2000 AD Alumni

Laura Sneddon is a comics journalist and academic, writing for the mainstream UK press with a particular focus on women and feminism in comics. Currently working on a PhD, do not offend her chair leg of truth; it is wise and terrible. Her writing is indexed at comicbookgrrrl.com and procrastinated upon via @thalestral on Twitter.

A trip down memory lane for me. Having organised the vodka bar press do in Soho to announce the payment of royalties (even retroactively) to 2000AD contributers on reprints I was in the midst of those discussions. Admitedly, my role was merely to distill the essence of the announcement down to the best spin. That was easily said as there were at least 3 versions at the time. It was clear even with the best on intentions on the part of Davidge and MacManus’ persistent efforts, Maxwell was not going to let the potential of money-earning copyright go. It was the best of times and the worst of times…

Great article Laura, thanks for all the work you’ve put in. Eagerly awaiting part 2…

Tony O’Donnell (one of Grant’s colleagues at Near Myths and later collaborator on some issues of Starblazer) told me that Grant discussed publishing an early version of Zenith with John McShane of Glasgow’s AKA Comics & Books back in the early 80’s. Obviously it didn’t come to anything but it raises the possibility that the idea for Zenith stretches back even further than the David Lloyd/Fantastic Adventure pitch (which would have been around 1985). Whatever happened it seems pretty likely that Morrison had a pretty good idea of what Zenith was all about before Fleetway came anywhere near it.

Before Kevin O’Neill snuck the credit cards in issue 36 – easier to do because from issue one every story had had a box that size on it containing a “thrill number” – there had been some individual art credits. Dave Gibbons got one on his Dan Dare episodes and Massimo Belardinelli had also received one. The real innovation in issue 36 was writing and lettering credits.

Recently I’ve noticed the odd story in 2000AD without credits – I haven’t looked to see if this is a regular thing.

By contrast to previous practise in their comics, Amalgamated had given writing credits in its juvenile story papers decades before this. By the time The Thriller was launched in 1929 (aimed at a slightly older demographic like 2000AD) they appear to only have been purchasing magazine publication rights, since a number of their authors held on to their characters and were able to make separate book deals for their Thriller stories.

Igor Goldkind – it certainly sounds like interesting times to say the least! It does seem like many were expecting the issue of copyright to be addressed only to be frustrated – but happy that royalties at least seemed sorted. The “fixed royalty” terminology is rather confusing though.

Deep Space Transmissions – ah, now that is interesting! I may drop the living legend that is John McShane a line before next week in that case.

David Hartley – ah I see, and I suppose afterwards everyone got art credits too rather than just some. Odd that some are appearing now without credit, possibly an error rather than a new direction I’d think…

It does seem that in “ye olde” days people tended to hold on to their copyright more often. I’ve found that looking into a lot of old characters they appear to be copyrighted to their creators, though in some cases that might be because the publisher no longer exists. I expect it’s probably more of a trend then as the idea of publishers owning characters as opposed to just publishing them hadn’t quite caught on? So comics were treated more like your average newspaper submission perhaps.

“Recently I’ve noticed the odd story in 2000AD without credits – I haven’t looked to see if this is a regular thing.”

I’d be pretty surprised at that and would suspect a lettering screw up more than anything else. About the closest you get is the odd story credited to T.M.O., which is usually the editor writing an unpaid strip – not sure if we’ve seen any of those lately.

Being the translator of some of the 2000 AD output to portuguese (and thus having to read the stuff VERY closely) I can’t recall any recent strip that has gone uncredited. Lots of the earlier stuff (particularly the Annuals) wasn’t credited, even after the official introduction of credit boxes, and lots of creators used pseudonyms for a time, but the recent stories have always been credited.

“2000 AD maintain that they have never sought creator owned work and the implication was always that comics were created on a work for hire basis.”

I’m not sure how this statement fits with the likes of ‘Button Man’ (1992-2007) and ‘Mazeworld’ (1998-2000), both of which were “creator owned” strips published in 2000AD, but maybe it depends who’s speaking for ‘2000AD’ (both strips pre-date Rebellion’s purchase of the title) and whether ‘sought’ is code for ‘solicited’ and/or ‘commissioned’, I guess?

Incidentally Laura, I interviewed Jon Davidge in 1992/3 for my Master’s thesis on comic creators’ rights and should have copies of the contracts that 2000AD were issuing at the time. I think there were two: one for WfH stuff and another for creator-owned strips but I’d have to check to be sure. I don’t know whether either might be of any interest to you for this series?

David Mosley – that would indeed be really helpful! I shall send you an e-mail. I’ve been looking through copyright law this last week and – in the basics at least – it does seem very straightforward with regard to contracts. It would be interesting to see the contracts that 2000 AD did end up introducing.

IIRC Buttonman and Mazeworld both started as projects for Toxic!, the creator-owned anthology, which folded before running either of them.

Button Man and Mazeworld aren’t the only creator-owned 2000AD strips. There’s a whole section visible here: http://2000ad.org/?zone=thrill&page=index

The most interesting, from the POV of these articles are, first, Hilary Robinson’s three series, as they were published in the same period as Zenith and later she successfully argued that she hadn’t signed over the rights to Fleetway either*; and, second, Big Dave, which is an unambiguously creator-owned series of Morrison’s.

(* Of course, handing Robinson back the rights to strips that aren’t particularly exploitable is a much different to conceding that Morrison owns ‘Zenith’, but it does set a precedent. Alan McKenzie also contends that he owns ‘Luke Kirby’, which also first appeared in this era.)

Yup, all will be in Part 2. Or possibly some in Part 3 seeing as the next bit has evolved into monstrous proportions!

These projects always seem to grow multiple legs on me…

“Recently I’ve noticed the odd story in 2000AD without credits – I haven’t looked to see if this is a regular thing.”

You’re imagining things. Everything is credited.

Kate, one of the reasons Hilary Robinson was able to regain the copyright on her work was because she had already self published strips with some of the characters (iirc) that appeared in Medivac 318

Comments are closed.