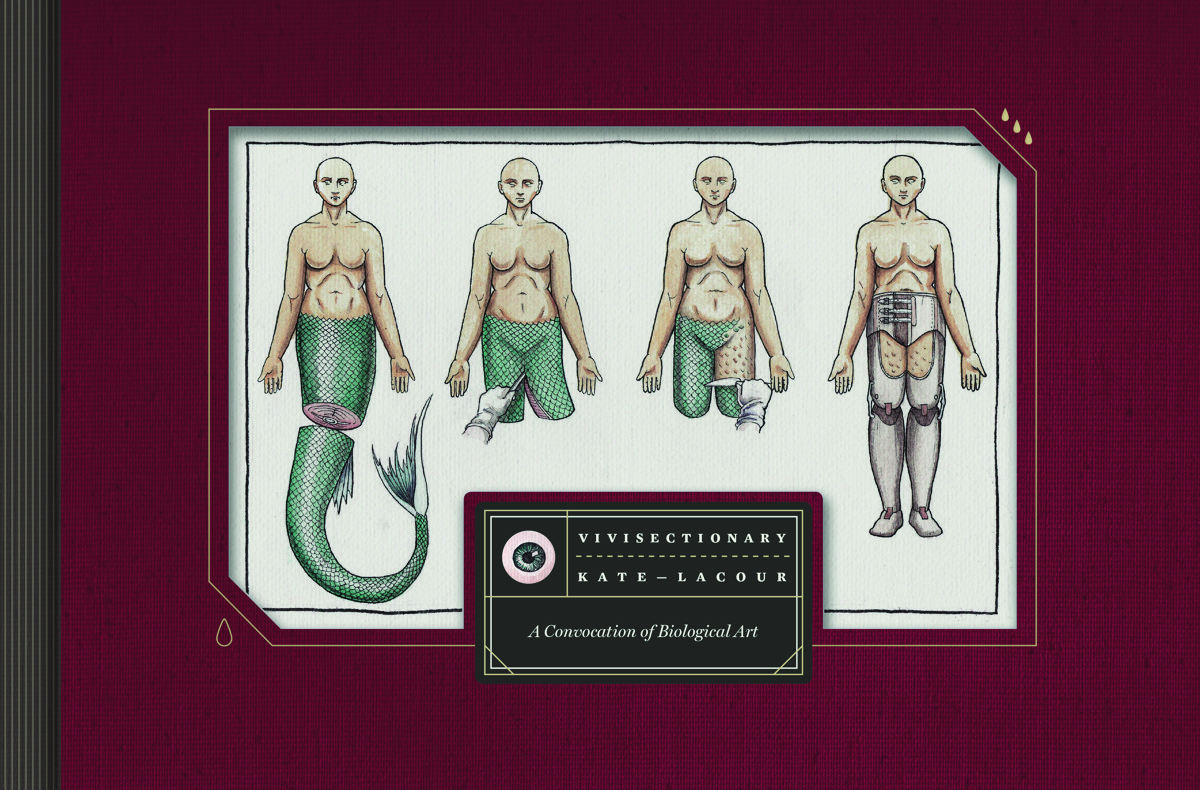

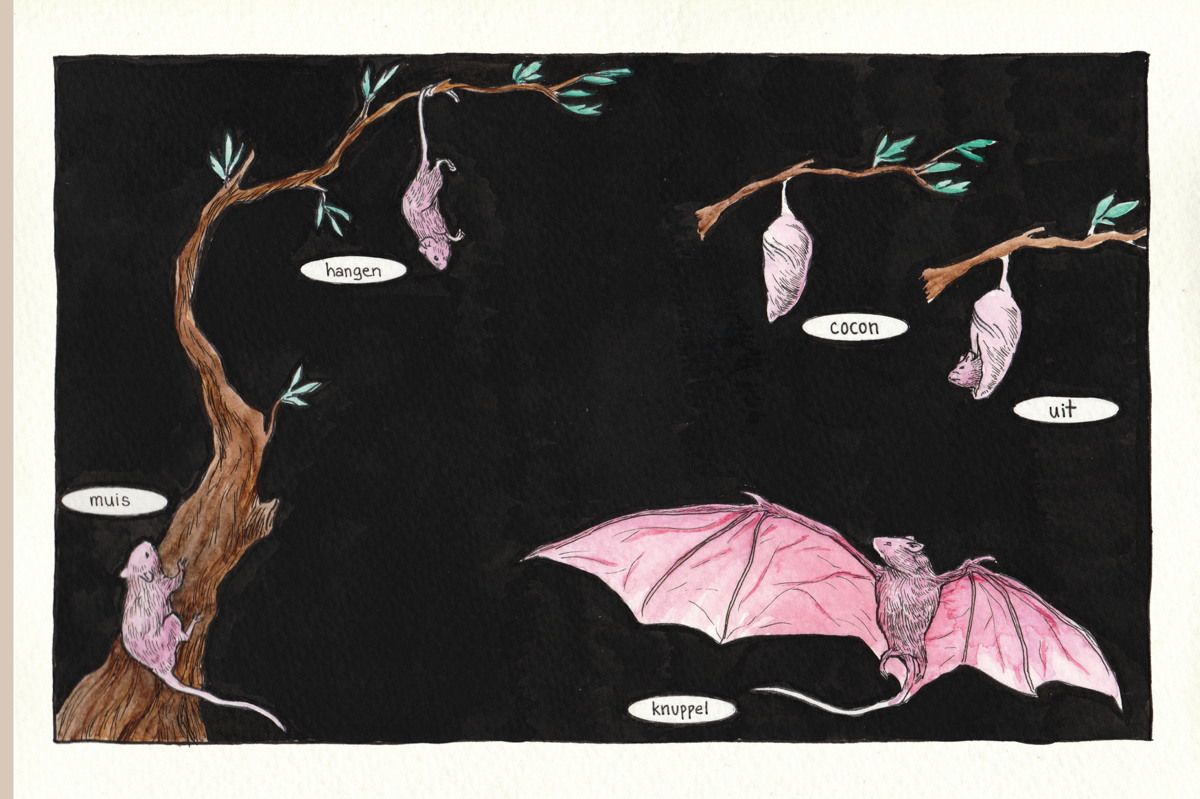

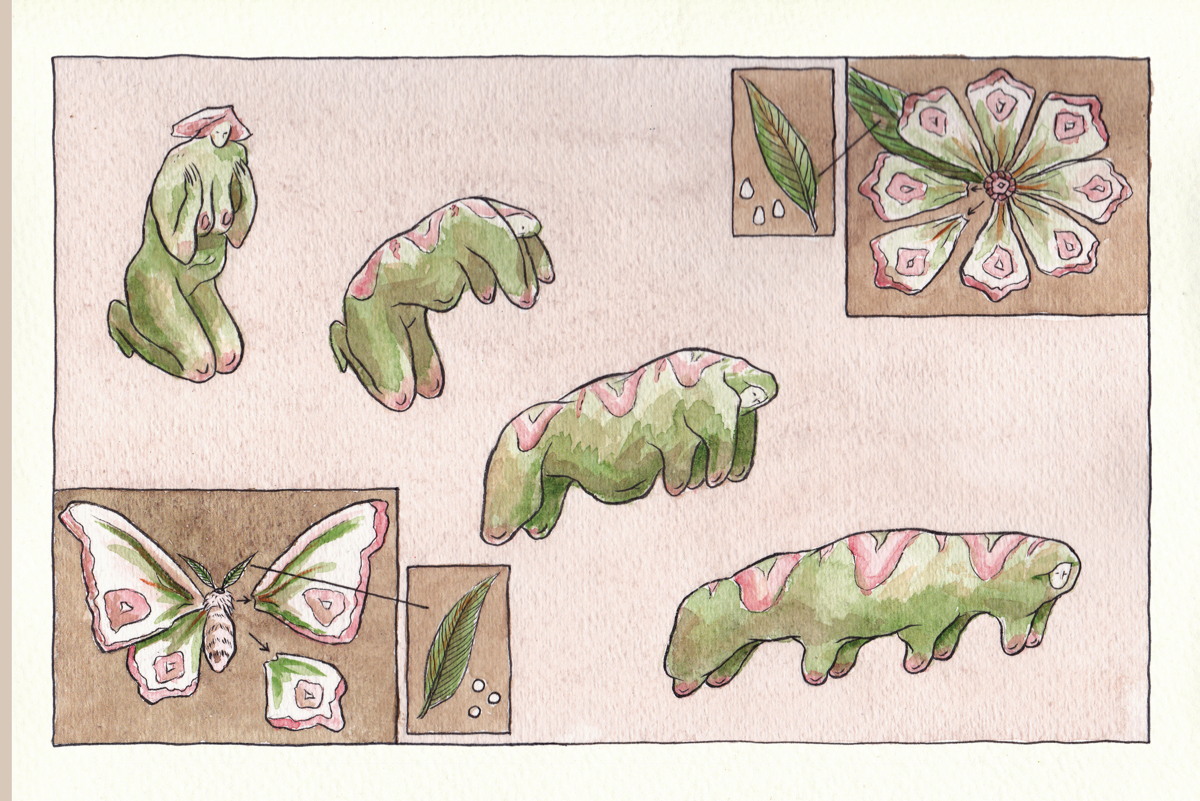

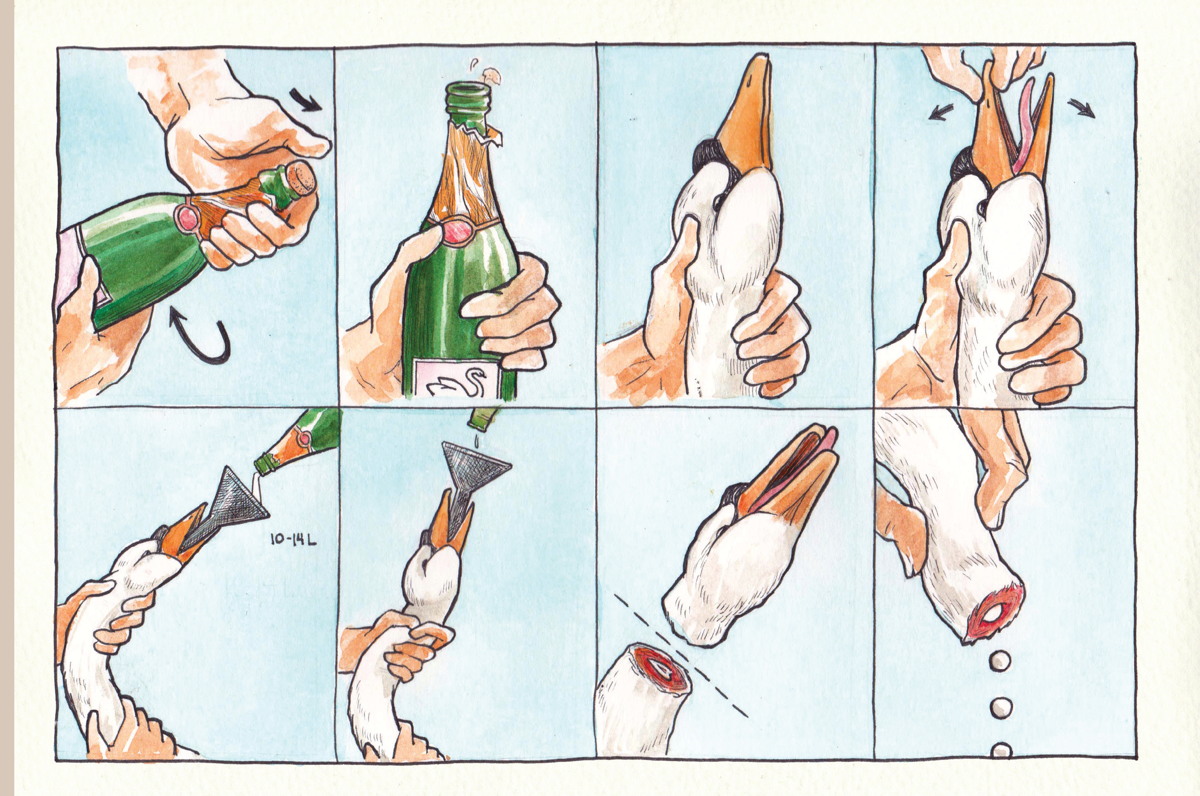

Kate Lacour is a cartoonist and art therapist based in New Orleans who has made a number of comics over the years like Zero Is, Eye See Eye, and The Disciple and received a MoCCA Arts Festival Award from the Society of Illustrators in 2016. Her new book is Vivisectionary, which was recently published by Fantagraphics, is a hard book to describe. The title is a portmanteau of “vivisection” and “bestiary” and the book consists of one page comics that feature strange transformations. Calling the book body horror, while partially true, doesn’t quite sum up the book which depicts transformations that range from the horrifying to the laugh out loud, disturbing to playful. It was a fascinating book and Lacour and I corresponded recently over e-mail about the comics she loved, the influence of dioramas, and book design.

You can find her website here.

[Content warning: disturbing imagery and violence]

ALEX DUEBEN: As a first question that I always like to ask people, especially for their book, how did you come to comics?

KATE LACOUR I had only a passing interest in comics until 9th grade, when I stumbled across a RE/Search book called Dangerous Drawings, which absolutely electrified me. It was full of interviews with people like Art Spiegelman, Dan Clowes, Julie Doucet, Chris Ware, Diane Noomin, Chester Brown, and Phoebe Gloeckner, and of course images of their art. I had a pretty sheltered life, and these comics presented worlds that were really developed yet also really raw – it was very powerful! After that, I read all the alternative comics I could. I’d take my allowance and board the train to New York City and go to Saint Mark’s Comics on the Lower East Side to scrounge around behind the superhero stuff looking for more. This must have been before the internet was the go-to way to make new discoveries. It was very haphazard, and it took a long time to find the comics that really spoke to me. I remember I randomly found the first issue of Black Hole while digging through a box of used Doc Martins in a vintage store. And, of course, that became a big deal for me. I was really taken with Dave Cooper, Dame Darcy, Phoebe Gloeckner, Julie Doucet, and Charles Burns.

Fourteen or 15 was a great age to be discovering this stuff. On the one hand, I was just a kid and wasn’t able to connect with a lot of this work on the adult level at which it was made. But on the other hand, it set up my adolescent vision of adulthood as being full of outrageous and weird possibilities, and a big piece my template as an artist and person was formed around that wild and weird vision of the world. Maybe if I’d discovered alternative music before alternative comics it would have been different, but growing up reading Eightball and Meatcake and Dirty Plotte, that was absolutely the club I wanted to be a part of, and the scene I wanted to participate in, in some way.

DUEBEN: You’ve made more traditionally designed comics in the past, how did the idea behind Vivisectionary start?

LACOUR: I was in the midst of work on a 36-page comic, Eye Sees Eye when I started these single-page pieces. The book was tough going; I was pushing myself to make the most humiliating and visceral work I was capable of. A lot of content related to childhood proto-sexuality, body horror – it was uncomfortable, and also the longest work I’d done up to that point. I drew a humorous one-page diagram piece as little break from that. It was satisfying to have something finished, and to do something funny. It was a palate cleanser. So I did more, and eventually started publishing them monthly in Antigravity, a local alt paper, and on the Study Group website.

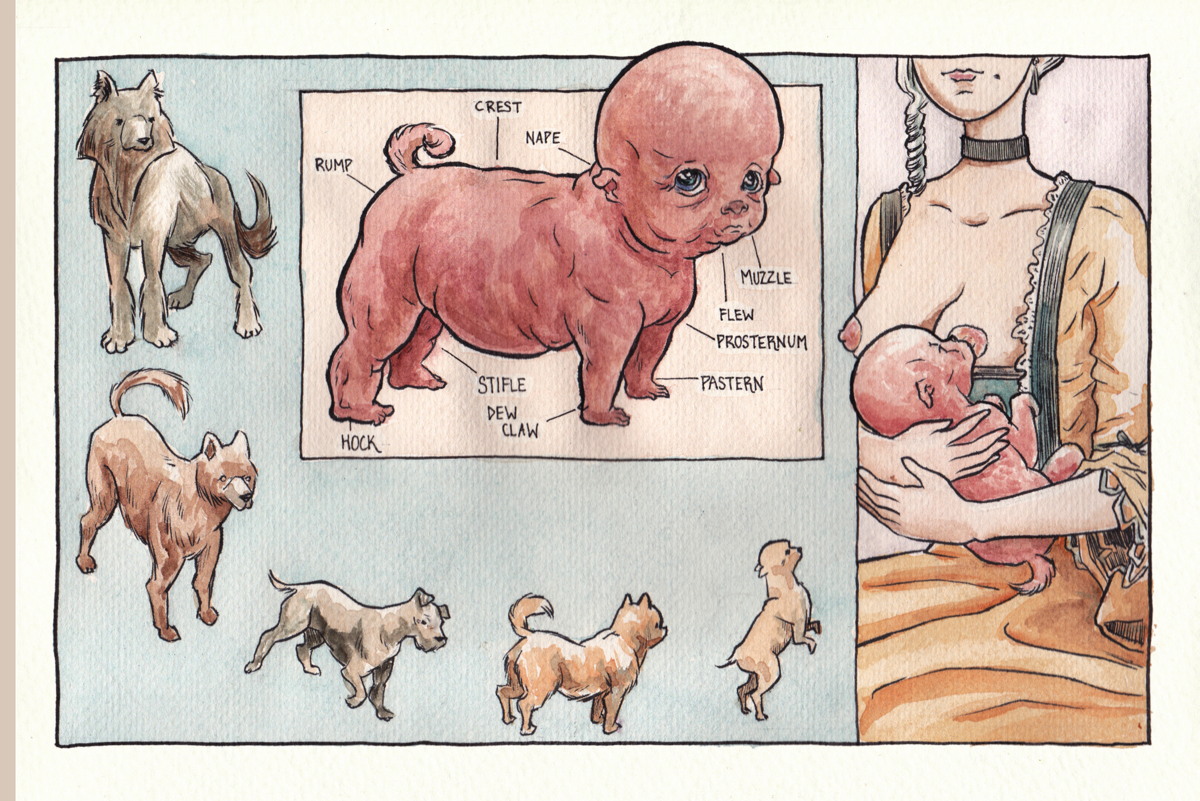

I didn’t plan an overarching direction, I just let whatever came to mind that month occupy the page. It’s funny, though, these pieces started off having to do with topics like food and animals, with a mostly humorous bent. And over time, they took a turn. The content got darker, with more things related to sexuality, bodies, and horror surfacing, along with themes from my personal life. I found myself drawing a lot of dismemberment, images of transformation, religious imagery. The things I’ve inadvertently come back to over and over since adolescence. I love that, actually. As an artist, you can choose a place “out there” in the sky to train your telescope, but ultimately you’re always just looking at some part of yourself.

DUEBEN: Which one was the first of these comics, do you remember?

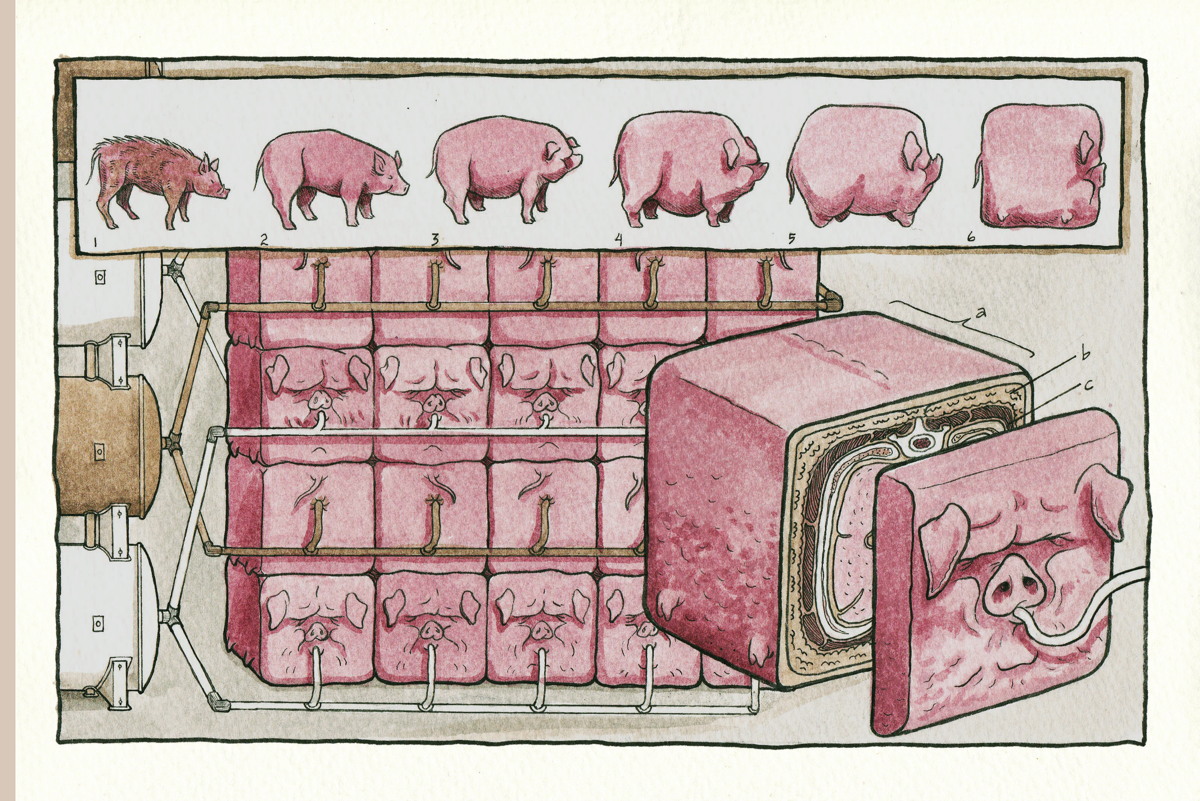

LACOUR: I think the first one I drew was the cubical hog. It shows the step-by-step breeding of pigs, down from these lean and powerful wild hogs, to bloated and immobile beasts that are effectively just living protein units. This total sequential debasement. Below that strip, there’s a cutaway diagram of the hog of the future, which is a massive, blind, sentient flesh cube with tiny little vestigial limbs, and a diagram of a warehouse where these things are kept alive, stacked one top of one another, with feeding and waste tubes connected to their anuses and mouths.

Now that I’m thinking about this piece, that one is actually pretty dark in and of itself! But at the time I made it, the humor there was a welcome break from the heavy body horror I was focusing on. I’m a really big nature lover, and the perversion of animals and natural processes by humans is incredibly bizarre to me, so most of those early pieces focused on that theme – our weird relationship with the natural world.

DUEBEN: The title is a portmanteau of vivisection and bestiary, but as you also explain in the final pages of the book, you compare it to a diorama. What about dioramas did you find so interesting and inspiring and full of possibility?

LACOUR: I do love dioramas! I’ve probably spent a hundred hours with the magnificent ones at the American Museum of Natural History. They take my breath away. But I also love the jankey ones at rinkey dink local nature centers tremendously as well. There’s something so thrilling about that little captive world, whether it’s really artful or amateurish. It’s naturalistic, but also stiff and artificial. It’s organic matter, but also plastic and resin. There’s some pageantry, and a very Uncanny Valley effect. But also, we have so little contact with real wild animals, there’s also a sense of this semi-living mythological presence in, say, a stuffed bobcat – like you might feel if you were a believer coming into contact with the relic of a saint. It’s almost a fetish object, in the spiritual sense, and very charged with our emotional and imaginative projections about the living natural world.

This imaginative projection of nature interests me even more than actual science. I’ve tried doing lab work, and I’m not too good at or interested in the actual stone-cold analysis and empiricism that real biology is all about. But I’m very interested in natural history, which is more observational than empirical, and is really entwined with the human story. The presence of the “human gaze” when we look at the natural world, and the questions about it that bother us. What is nature – is it our dominion? Our master? Are we really a part of it?

And I feel like that irreconcilable relationship is really analogous to our own physical bodies, the other thing I’m so interested in. Like, is this body my tool? My self? Or is my sense of self a property of my body?

Taxidermy dioramas totally crystallize this impossible relationship between human and animal, and between gross physiology and the actual animating life force. And it’s all staged like a dreamy little atmospheric world you could just crawl into.

DUEBEN: When thinking of similar comics, I thought of Rube Goldberg where it wasn’t about narrative, it was about this implied story in the art and the transitions. What were the comics that helped shape your thinking about this book and your work more generally?

LACOUR: That’s a great comparison! I’m not sure that any existing comics played a significant role in the narrative framework for the pages. The biggest influence there, apart from obviously charts and diagrams, was predellas, which is a style of altarpiece that was popular around the Renaissance. I saw a number of these when I visited Italy as a kid, and they were pretty striking.

They way I understand it, a predella usually features a large illustration of Jesus or the Madonna and Child or what have you, with a series of small panels lined up alongside or below it that tell a story, like scenes from the ministry of Jesus, or the miracles and martyrdom of a saint. I assume the sequential art was aimed at giving an illiterate public access to these stories. I liked how stiff and instructional they looked, and how they provided a sub-story that related to the main subject of the predella, which would itself usually be packed with symbols and iconography that conveyed other information.

Later, when I saw Krazy Kat comics, the tiny strip that Herriman would sometimes draw below the main story charmed me the same way – I love the nested and interlocking narratives, which were laid out in almost the same way as the predellas. That’s a formal narrative relationship I’ve consciously tried to reproduce.

In terms of content, though, the dark and transcendent sensibility and polished style of people like Nina Bunjevac, Jim Woodring, and Al Columbia was incredibly inspirational. To be able to draw a vision from behind the veil with that kind of precision – you can see through work like theirs that it’s not impossible. And that has helped me to begin developing a sort of moral courage when it comes to drawing.

DUEBEN: The work in these pages is so different, it’s united by this similar approach, and people will respond to them differently. I saw Plate 6 and thought, someone somewhere is probably trying to make this happen, but in the course of the book, some were disgusting, some inventive, some made me laugh out loud. Were you thinking as you were writing and drawing them about wanting different approaches, different reactions?

LACOUR: That’s a great response! These were drawn monthly over the course of 6 years or so, and as stand-alone pieces, they reflected my thoughts at the time I created each one. Many of the funny pieces were painted in good times, some of the more disturbing ones were painted when life was difficult. There’s one, for instance, that shows faceless angelic beings grinding up human bodies in a meat grinder, then using the flesh-paste to fill hourglasses strapped to the back of each hobbled person on a sort of karmic wheel made of scaffolding. I had recently become pregnant, and was constantly ruminating on the cycle of life – it was a weird ray of morbidity shining into a happy moment, and it showed up in this piece.

So, many of them are snapshots of physiological or spiritual problems that held my attention at a particular time. Others are different silly or scary facets of the same thing that interests me. I actually find that kind of satisfying – the very different and disorienting ideas that bubble up around a single concept. You can relate to grief with the distance of gallows humor one minute, and be totally stricken in the next. Or you can be juvenile about sex one moment, and then almost hideously earnest about it the next. And of course, the things we are both drawn to and repelled by are more deeply charged than anything else, and so much fun to explore from different angles. I hope that the shifts in tone don’t break the spell for the reader, and instead make contact with different emotional keys.

DUEBEN: You made these and printed some as a short comic, but as far as working with Fantagraphics and making a book, what were you thinking about as far as the design and what you wanted the book to be?

LACOUR: I was very excited to collect these, but I quickly decided I didn’t want the book to be a collection of single-page, stand-alone gags, like a “Best of the Far Side” collection. I wanted the book to have an overarching narrative, even an abstract one, and I wanted it to have a feeling as an object. So the goal was to make it a meaningful physical thing and to embed a connecting story.

I originally thought of designing it after a child’s science textbook – I love and collect them – but the incredibly talented designer at Fantagraphics that I got to work with (Jacob Covey) suggested modeling it loosely on a vintage encyclopedia. It was a great idea. About 100 years ago, encyclopedias were sold door-to-door, often to lower and middle-class families as this way for their kids to grow up with access to knowledge, maybe grow up to become doctors or teachers or engineers. And the tone of those old books was always very grand and formal, the illustrations very superlative, the binding was serious and almost regal. Like you were taking up the mantle of greatness by engaging with it. So that kind of rich design and fancy binding became the template for the book as an object. And, of course, the cut-away cover also reflects the surgical themes.

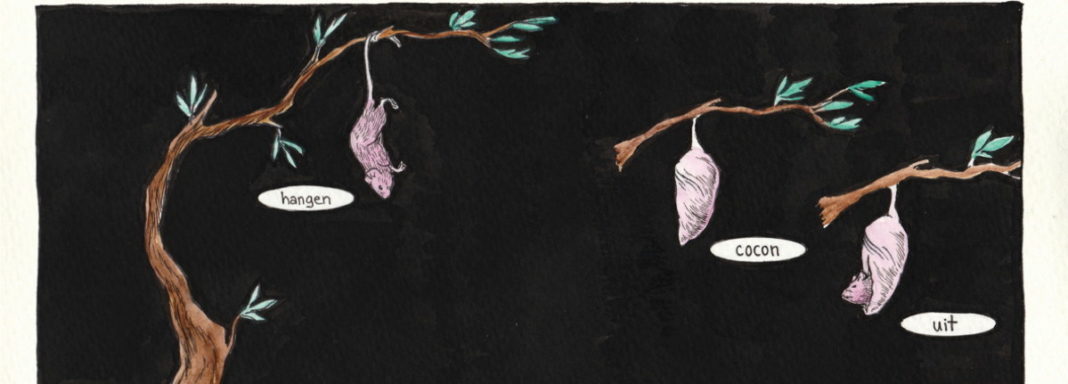

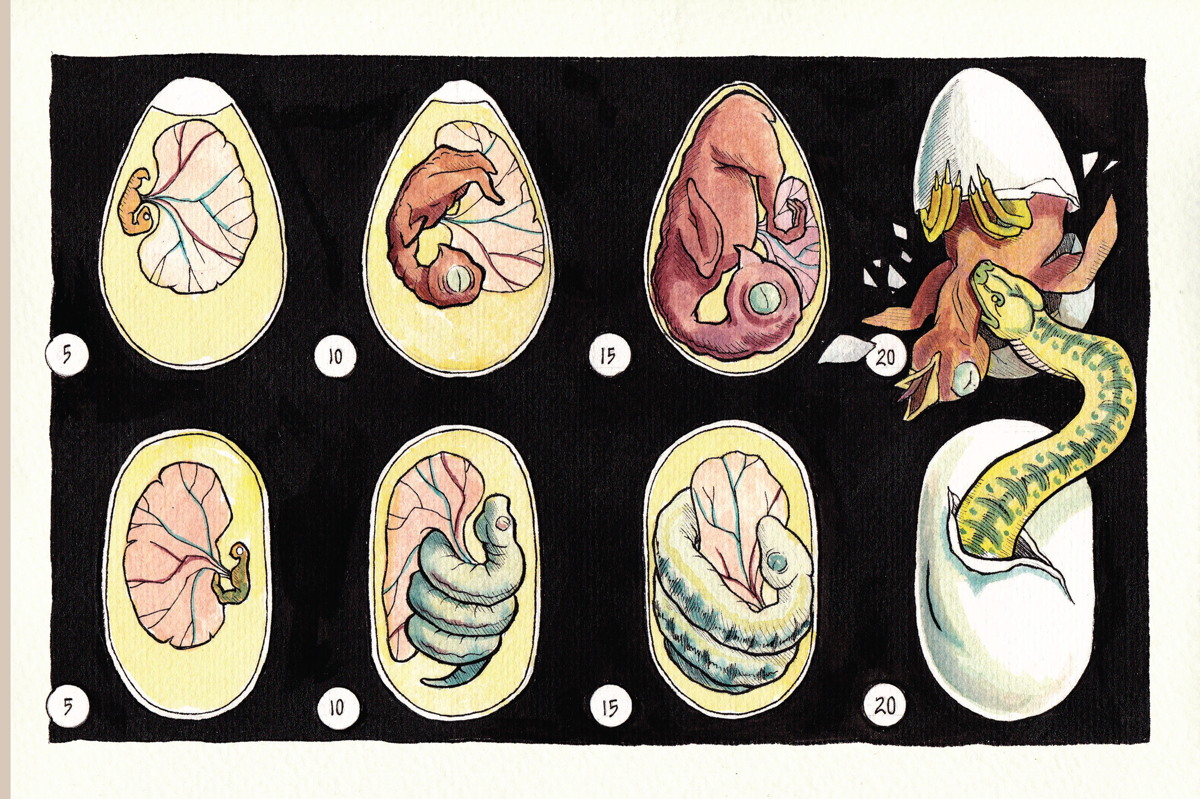

We moved the diagrams to separate page-spreads to keep them visually distinct, so they can each function kind of independently. That also allowed me to add art to each left-hand page, which was an opportunity to build in a new narrative, pieces of small sequential art that would be seen on consecutive pages, rather than adjacent panels. And then I inserted regularly spaced pages of full-spread anatomical art that would show a sequence, but that wouldn’t be consecutive. So the book has a few concentric visual stories, which complement, but run parallel to, one another.

DUEBEN: Do you want to keep working in this way? Are you interested in exploring something different? Where’s your interest right now that you’ve finished this book?

LACOUR: I’d love to continue with this series – I’ve lived with it for some time and the language of it comes naturally to me. It’s wonderful to feel comfortable with a way of expressing ideas. But my gut says this has run its course, and there’s another project I’ve been feeling driven to do. I think that’s going to mean moving back into a more traditional narrative structure, and instead pushing the boundaries of subject matter. It’s going to involve a lot of poetic text, passionate eroticism and weird body imagery. So my challenge will be to level-up my figurative drawing and storytelling skills, and lean into that moral courage that’s required to draw ideas outside your depth of understanding. I’m dreading it but also thrilled by the idea of doing work that feels ugly and uncomfortable again, and that will demand I reinvent everything.