One thing is immediately clear about Edinburgh-based cartoonist Will McPhail, best known for his long-running New Yorker cartoons: he is very self-aware. And he uses that self-awareness with deadly accuracy to lampoon and illuminate daily life. His new graphic novel, IN, is a story about an urbanite named Nick who is having trouble connecting with others, but who slowly begins to discover a more authentic world. It’s a semi-surreal and delightful journey with evocative watercolors.

In this interview with The Beat, McPhail discusses IN, the cartoonist’s first graphic novel, which comes out on June 8th from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. I had to laugh to myself because our Zoom interview reminded me of his comic showing how video meetings hide all the laundry, wild animals, and dead bodies in the unseen parts of our rooms. We also discuss McPhail’s background, process, and what he was really thinking during his first conversation with his agent about IN!

Consider yourself warned: There are a few mild spoilers for IN’s content below. This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Kerry Vineberg: I read a few other interviews with you and learned that you studied zoology!

I don’t know if it’s because I like drawing the animals for the cartoons, or because I’m retroactively trying to make my degree more worthwhile after the fact, so I can say, “Look, I’ve made use of it, because now they’re in the New Yorker.”

Vineberg: Does that play into your view of humans at all? As an animal?

McPhail: Well, we definitely are animals. I mean, what other kingdom would we be in… Protozoa? Fungi? And particularly now, while we’re all locked away, it does feel like we’re also caged.

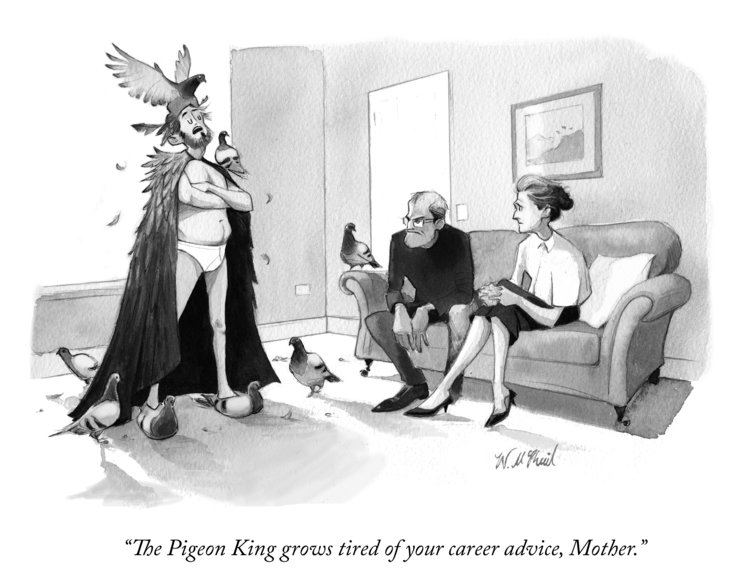

There’s a pretty much surefire well of humor when doing my New Yorker cartoons, to just find similarities between behavior with animals and humans. And then cross it off and draw the animals and it’s immediately a more relatable cartoon. I do it with pigeons all the time. Or rats, which is a worrying thing. I compare myself to vermin constantly. [laughs] Yeah, there’s similarities between all of them.

Vineberg: You’ve done a lot of short pieces, but the story arc gets to expand a lot in IN. When going from strips to a full-length graphic novel, was there anything you had to learn about or do differently?

McPhail: Oh, totally. It’s the first thing that’s longer than four pages that I’ve ever done. So it was all learning. I really didn’t know what I was doing at all. I still don’t!

So it was jarring. But also, at first, I felt like it was really freeing. Because with the single panel stuff that I mostly do, you’ve got to kind of cram this whole world into one panel: the setup, the premise, the punch line. Everything’s got to exist there.

Whereas with IN, the graphic novel, I could go really slow and build things up carefully and not feel the pressure to be funny all the time. And just literally had more space to work on the page. So that felt immensely freeing at the start.

Then when I finished it, and went back to doing my usual New Yorker submissions, I thought, ‘oh no, this is better. I can just write about parrots and… doesn’t matter.’ That’s way more freeing. And not having to worry about how it will affect the storyline. So I can go between the two. It feels like a shift of gears, more than anything else.

I feel like I have to be more conscientious while I’m writing a graphic novel, because I have to care about the future and how things affect stuff. It’s just a different gear. I love both. The New Yorker cartoons now feel like this little release for me, like this pressure-off treat that I get to do after slogging away on the book. Also because the book was so sad.

Vineberg: Definitely, it was emotional.

McPhail: Yeah. I mean, it was always going to be. When I pitched it to the publishers, the story was essentially written, but it definitely became more sad. I finished it during the pandemic. And so I was sort of trapped on my own, writing it. And also Phoebe Bridgers‘ second album came out, which is just the saddest thing in the world. I had that on a loop while I was finishing it. So I blame Phoebe Bridgers.

Vineberg: What do you like about her or what drives you in the music?

McPhail: Oh, she’s actually just a genius. Incredible songwriter. She writes this essentially pop-folk music, but it’s just weird enough to be elevated above everything else. And she’s this genius lyricist. Her second album, Punisher, is a masterpiece. It’s so good. Now when I look at my book, I can see those pictures, I hear all the songs from the album. It’s sort of impregnated in it.

Vineberg: Any songs people should be listening to while they’re reading IN?

McPhail: Specific songs… “Chinese Satellite.” “I Know the End.” It’s all amazing. “Graceland” too. It’s awesome.

It’s weird, when I’m working on something bigger, I try to not read or be influenced by stuff that’s from the same medium or genres. I didn’t read any graphic novels or cartoons in that time. Because I’m too scared that it will influence me. That I’ll read, like, Erin Williams‘ book Commute and I’ll think I need to be more gritty, add social issues. I’ll try and force other people’s work into mine where it doesn’t belong. You know what I mean?

So I’ll listen to music and watch films and stuff from other genres that will influence me.

Vineberg: Interesting. Any notable films?

McPhail: Yeah, I’m always drawn to stuff that’s got a very real feel, but also has this element of fantasy, which the book’s got. So stuff like Groundhog Day.

Vineberg: You mentioned the pandemic earlier. Did any aspects of the story change or take on additional weight because of the pandemic?

McPhail: I wrote IN long before the pandemic, but there are obvious themes of isolation during the book. And as we were all thrown into isolation afterwards, it probably did make me sympathize with the character Nick a little more than I did already.

But I’d say more than it affecting the book, it was a case of the book helping me deal with the pandemic in a lot of ways. All my friends and everybody I knew, when we were locked down, we all kind of suffered with this lack of direction, not knowing what day it was and where to aim for. Whereas I had this thing that I had to finish, and I knew how to do, and so I had this obvious direction to go. Whilst I would normally have been feeling lost a bit during the lockdown, I felt like the book helped me deal with it, rather than the other way around.

Vineberg: Super interesting. Do you recall the original vision for IN?

McPhail: Well, I got an email out of the blue from Heather, who would later go on to be my agent, asking if I’d ever thought about doing a book. And I lied and said that, yeah, of course, I’m thinking about it right now! Never stopped thinking about it. Whereas what I was actually thinking about was parrots and how we don’t give them enough credit for being able to speak English! Anyway, sorry, got angry for a second!

So I lied and then immediately went out and bought 10 Moleskines. And I literally wrote out “book ideas” at the top of the page. So I feverishly started writing down ideas.

I’d always been fascinated by the mechanics of conversations and how certain combinations of words or even letters, if set in the right order, and at the right time, the right cadence, can change how conversation works, and can turn what feels like a performance into something completely different. Where the performance goes away, and you’re just you and this other person being completely honest with each other.

That felt like a rich enough idea that I could dive into and build this world around. So that was one of the very vague ideas that I sent to her, and she was like, “That one.”

Vineberg: You seem like you’re pretty busy, given that you’re doing many ongoing strips. How long have you had this graphic novel in the works? And how did you fit it into your schedule?

McPhail: I guess it’s been a year and a half since I first started. It feels like a long time since I finished. Maybe 18 months, something like that. I did keep drawing the New Yorker cartoons throughout the process, because it felt like a welcome gear change, like I said before.

I think there was a point where at the end, heading towards the deadline, I was getting very stressed. And I stopped doing the New Yorker cartoons. The way that I deal with the New Yorker cartoons is I sort of let vague ideas percolate in my brain throughout the week. And then I draw them all on Tuesday, which is the submission day.

So it was only really a day out of my schedule from writing the book that I had to squeeze in the New Yorker stuff too. So yeah, it was manageable. It’s not like I’m down in the mines. I sat at a desk with a pencil.

Vineberg: Fair enough! Did you draw inspiration from a particular city for the setting?

McPhail: Yeah. Before the pandemic, I spent a lot of time in New York because of the New Yorker magazine. So the book is kind of a mix between Edinburgh and New York, different elements of each in it, pretentious coffee shops and stuff. But the place itself isn’t that important, really. Just a vessel.

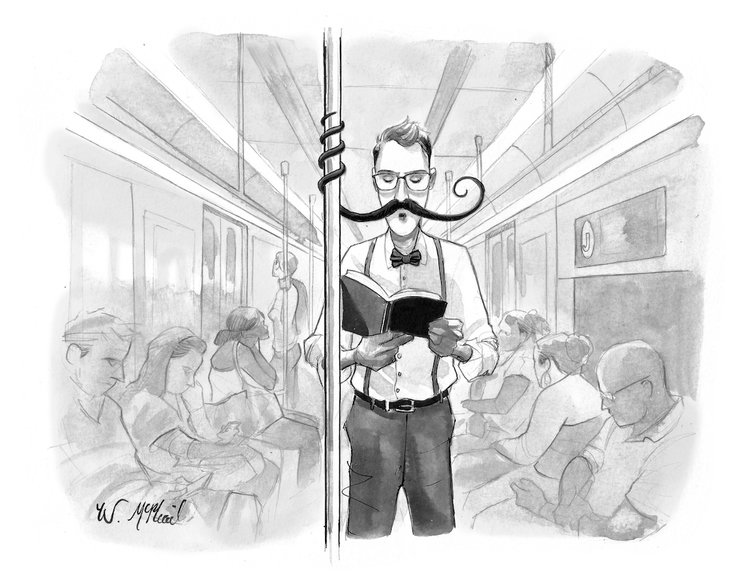

Vineberg: What is your drawing process and medium?

McPhail: It’s pretty old school. It’s just pencil and watercolors generally, on watercolor paper. All my New Yorker cartoons are that. For the book, there was a lot of digital moving and shifting around we had to do because of the text and the panels. So a lot of that was done digitally, particularly the color stuff. That took a lot of extra work.

Vineberg: Is there something specific that draws you to watercolors?

McPhail: When I was at university, I half-thought I’d be a wildlife artist, because I like drawing and I’m doing this stuff about animals. Back then, I did a lot of oil painting of animals and stuff. Then, when I started doing the cartoons, I would use watercolors and it was just astonishing how much quicker they are than oil paints.

So it was really the speed. You got to work fast with watercolors. And I’ve got a small attention span, so they’ve suited me well.

Vineberg: You have these really iconic round eyes for your characters. What went into that stylistic choice?

McPhail: First of all, they weren’t always like that. I found that after a little while. So I’ve experimented with different sorts of eye. I think it’s just, I can be at my most expressive with a good, round eye. And I really love the minutiae of just tilting an eyebrow or an underlid the slightest bit to completely change what expression they’ve got. And I feel like those nice full eyes are perfect for manipulating different emotions with.

Also, I think people are at their funniest when they’re panicked. I really want people to look sort of scared and nervous. And big round eyes are perfect for that.

Vineberg: There’s a little bit of anxiety.

McPhail: Anxiety, yeah, that’s my brand. See, when I started drawing and all I read was Calvin and Hobbes, I just ripped off Bill Watterson and did little circle-dot eyes. And as wonderful as they are, they ask the reader to interpret the expression because they’re sort of always expressionless. I started like that, and then found my own way.

Vineberg: So, in what ways would you say you’re like the main character of IN versus not?

McPhail: It’s been described as semi-autobiographical and I kind of agree with that, not entirely. Nothing that happens to Nick has happened to me really in the book, besides the very first chapter with the bowl, the swimming bowl. That really happened.

I’ve lost people that I love. And that affected how I wrote about grief and mourning in the book. And I’ve had these rare, transcendent, dreamlike conversations that seem just unlike anything else in their intimacy.

But I’ve never connected with a plumber in my bathroom. The actual events that happen in the book haven’t happened to me. It’s fiction that I’ve informed with real life. I would say that the book is at its most autobiographical with the humor. There’s a lot of humor in there that I felt like I could use because it was self-deprecating, if you get me. I was lampooning and teasing myself. And so I felt like I could get away with it.

Like I say, the pretentious coffee shops and stuff like that, I’m teasing them because I actually go to those places, and I love them. So I felt like I could tease myself about it. Or there’s a bit where Wren is teasing Nick about being a “woke boy.” I feel comfortable making those jokes because I am a woke boy. So I feel like it’s self-deprecating and teasing me as opposed to mocking the idea of being woke, because that’s what I am. I feel like that’s the autobiographical part. I’ve put myself into the jokes almost at my own expense, really, for the humor.

Vineberg: Also, I thought the awkward silence parts were great. They’re just staring at each other.

McPhail: Yeah, there’s like three lines of dialogue in the whole book. It’s mostly brooding glances between people.

I think there was a lot more dialogue in it, and I more and more took it out. It’s that whole thing of not wanting to spoon-feed people and having faith that your audience are smart, and they’ll be able to interpret and read into it themselves rather than you just giving them everything.

Vineberg: I appreciate that a lot as a reader. You have some really great surreal scenes. Was there any reference imagery you drew from there?

McPhail: Oh, yeah, for all of them. They’re the scenes when Nick connects with people and it goes into color. Those scenes, they’re all kind of based on some particular thing that I’ve experienced. Like Nick’s nephew Owen’s world. He goes into this terrifying world of these little monsters in this desert, that’s at first joyous and welcoming and then turns terrifying.

The theme behind that was me spending time with my nephew. You’re always kind of on a knife edge with him, between him worshipping you and you being his worst enemy. I wanted to get that across.

For the actual visuals of it, me and my friends had gone to this fire festival in Edinburgh called Beltane, this pagan ritual fire festival. And there’s like, naked people covered in blood, running around with these big fire sticks. It was based on that, slash Burning Man. This sort of pagan festival thing.

So, the different worlds. The key that Nick needed to access his mom’s (Hannah’s) world was to realize that he had been defining her as his mom, and not this individual person that exists outside of his relationship to her.

For the look and feel of her world, I wanted it to be the polar opposite to what you would stereotypically think of a mother’s world, you know, warm and welcoming, bright and nice. I wanted it to be weird and dark and sinister and unusual.

Vineberg: I thought that a really powerful theme in IN was learning to genuinely listen to another person. I was curious if there were any lessons from your own life that you drew from there.

McPhail: Oh yeah, of course. I’m a megalomaniac white man [laughs] who has been conditioned by society to talk so that people will listen. So yeah, I’ve definitely learned that lesson that listening is the most important thing in the whole world.

Genuinely, I’ve always been the quiet one. I was raised in quite a big, loud family. And I don’t know if it’s being a middle child or something. But yeah, I was always the guy who’s just sort of sitting back, taking everything in, listening and digesting and speaking twice a day, but those two things being well thought-out stuff that I’d really considered. So I don’t know if that was just a result of my upbringing.

There’s an irony about explaining to you how I listen to people!

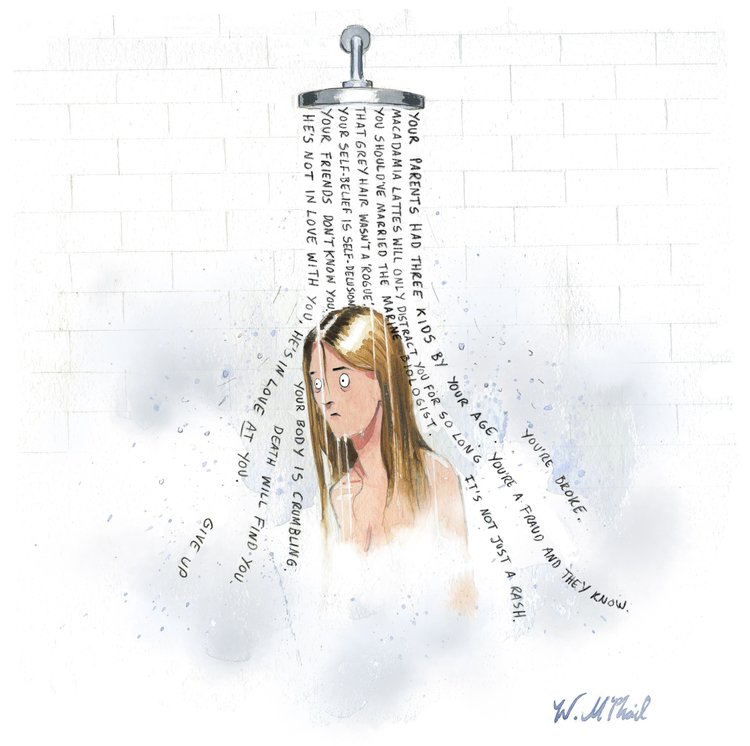

Vineberg: Amazing. Do you have recurring humor themes or frameworks that you pull from if you’re stuck?

McPhail: Oh, geez. Oh, yeah. That’s every week with the New Yorker cartoons. Every Tuesday. Yeah, I find the well dry. It’s a difficult thing. I think there probably is a way to work out the maths of how to come up with like, perfect joke caption cartoons. So that you find an area, and then you go, this plus this equals the joke. But honestly, I’ve resisted doing it, because I like the unpredictable magic of finding something that’s funny, for a reason that I don’t necessarily understand.

So the best that I can do is find an area that I think there might be humor in and then just hope that my sense of humor shows up and gives me something, you know? It’s kind of like, the cartoon that you’re going to draw is the result of the sense of humor that you’ve forged your entire life, up until the point where your pen touches the paper. You’ve got to cross your fingers and hope that it shows up.

It’s definitely the more enjoyable way too, because that way I enjoy the cartoons as they come to me at the same time as well. (As opposed to it feeling like a job that I’m just grinding out.)

Pre-order IN now, coming June 8!