Late last week it was announced that French cartoonist Jean-Jacques Sempé had passed away, aged 89. Better known to US audiences for having produced some 106(!) covers for The New Yorker, in France he is famous for his prolific cartoons and for having co-authored the classic children’s story series Le Petit Nicolas (‘Little Nicolas‘) with renowned comics writer, editor, and Asterix co-creator René Goscinny.

A sad day for the cartooning world. 😞#ripsempe

Read more: https://t.co/Lboi28xXu4

— National Cartoonists Society (@NatCartoonSoc) August 12, 2022

Born August 17, 1932 in Pessac, a town near Bordeaux, France, Sempé had a tough upbringing. Born out of wedlock, raised by foster parents before being reclaimed by his mother, and enduring a violent alcoholic stepfather.

Easily distracted and undisciplined, at 14 he was expelled from school and struggled to secure continuous employment – taking on various small jobs. At 17 he lied about his age and joined the French army in 1950 for a simple reason: “That was the only place that would give me a job and a bed”, he said in a 2006 New York Times interview.

Despite making it into the army, he was often reprimanded for drawing while on duty. The boy of 12 that had started by drawing Mickey Mouse and humorous doodles while listening to the radio had become a young man that couldn’t stop sketching. He managed to get some early sketches published in the Sud Ouest newspaper under a pseudonym (‘DRO’) before becoming confident enough to sign his published drawings with his own name for the first time in the April 29, 1951 edition.

On looking back on his chequered work history, in a 2001 Guardian interview, Sempé said:

“I had a go at all sorts of things before taking up drawing, but none of my jobs lasted very long. I tried to work for a bank, the police, even la sécurité sociale , but everyone rejected me. I chose drawing because, well, I had to do something, and I had exhausted all my other options.”

When it was discovered that he had lied about his age and falsified his papers he was summarily discharged from the French military and at that point he decided to take drawing seriously. He stayed in Paris and tried to secure work as a cartoonist in the French press – but it wasn’t easy.

In the Guardian interview, Sempé also said:

“After that it took me a long, long time – about 15 years – to make a decent living out of it. It’s not easy to place humorous drawings in papers or to sell books of pictures, and I lived in tiny attic rooms for a long time. You can persuade yourself afterwards that it wasn’t such a struggle, but if I hadn’t been so young…”

After much graft and hard work, Sempé managed to get his illustrations and cartoons into French newspapers. He won an amateur artist award in 1952 and managed to have his work regularly published in Paris Match magazine. Overseas he even managed to have his work published in Punch and Esquire.

#RIP French artist Jean-Jacques Sempé who has died at the age of 89. Sempé contributed many cartoons and covers to PUNCH. Some of his colour work. #illustrations pic.twitter.com/eH7XGR6Yqu

— Punch Cartoons … and more (@PunchBooks) August 12, 2022

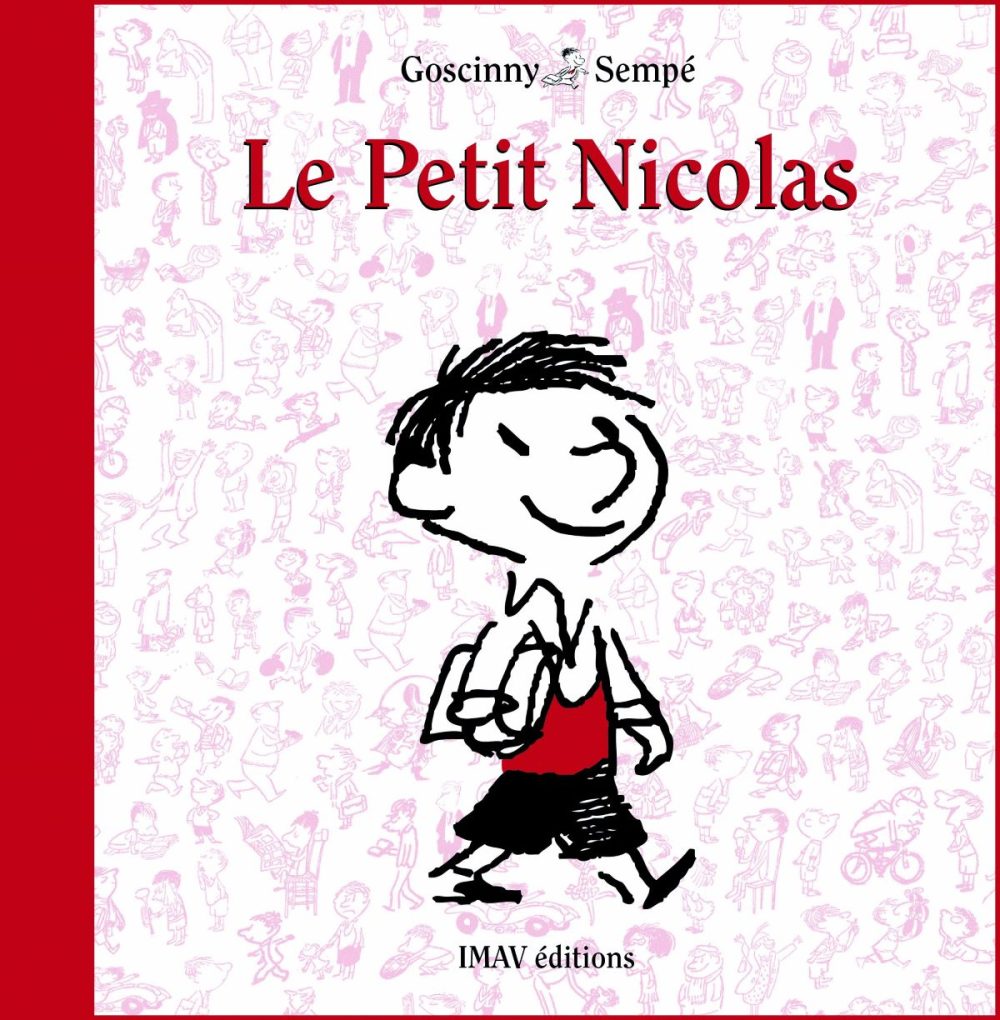

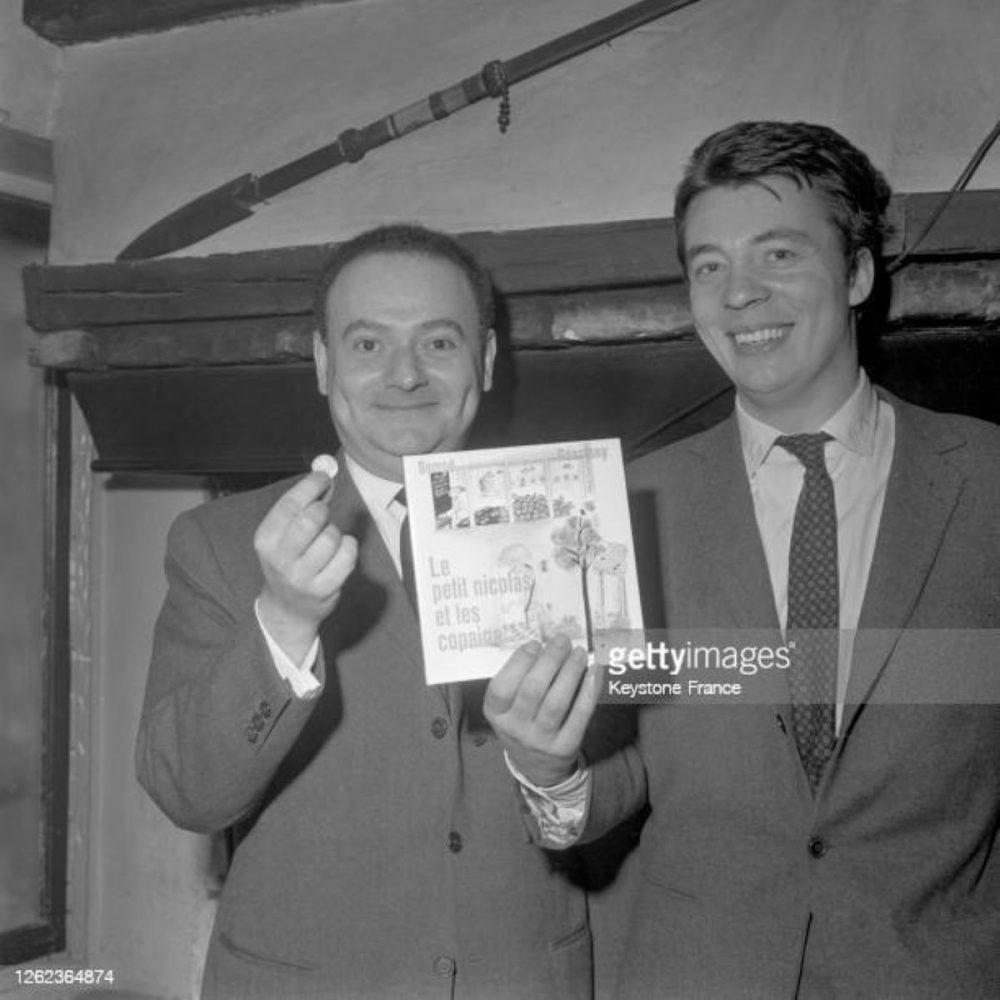

In 1954 Sempé met Rene Goscinny at the offices of a Belgian press agency and they became fast friends. This friendship bore fruit when the pair came up with an early iteration of the Petit Nicolas charactor while working at Belgian newspaper Le Moustique – on which Sempé would provide covers, cartoons, and sketches, and Goscinny was writing detective serials under a pseudonym. An offhand character Sempé had drawn of a little boy was given the name Nicolas and a prototype of what would become Le Petit Nicolas comic strip was commissioned which saw publication in September 25, 1955. Only 28 boards of this early iteration of the character were produced, with Goscinny writing under a pseudonym. The series was abruptly abandoned following a dispute about creators rights leading to both Goscinny and Sempé leaving the paper.

In 1959, Goscinny was requested to provide a humorous tale by the editor in chief of newspaper Sud-Ouest Dimanche. Goscinny wanted to revisit the Petit Nicolas character but Sempé said he didn’t feel comfortable drawing a comic strip, as he felt more of an illustrator. The format was reworked into short, illustrated text stories written from the child’s perspective (unique at the time) depicting an idealised vision of childhood in 1950s France. It debuted March 29, 1959 and proved a hit. This one-off tale continued.

When Goscinny’s influential children’s magazine Pilote began publication in October 1959, the character joined the roster and featured there – alongside Goscinny and Albert Uderzo’s soon-to-be-classic Asterix comics – until 1965. By the end of the character’s run, over two hundred Le Petit Nicolas stories had been produced by the pair.

Le Petit Nicolas has remained popular. The stories have been translated into around 30 languages – including English – and in France the character been adapted into a 2009 animated tv series, a radio play, and several movies. When Goscinny’s daughter Anne unearthed 10 unpublished stories in 2004, Sempé returned to the character and illustrated them.

While famed for his co-creation, Sempé never abandoned freelance illustration and cartooning. Continuously sketching and producing work for local and occasionally foreign outlets. Between 1965 and 1975 he had a steady gig at weekly news magazine L’Express, and he also had work published in Le Figaro – France’s oldest newspaper still in circulation.

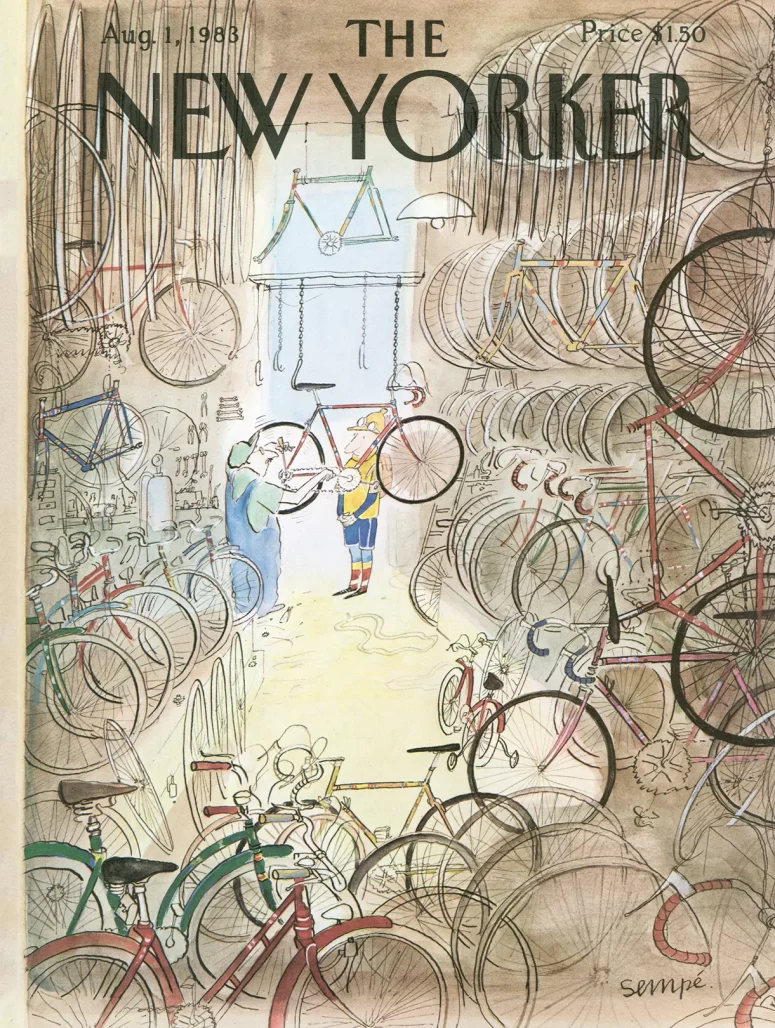

For Sempé, he believed his biggest break of all really came from getting his work published in the New Yorker, in his late 40s. From 1978 onwards he produced over a hundred different covers for the prestigious American periodical – which brought his work to further international attention. In 2014, the New Yorker’s Mina Kaneko and art editor Françoise Mouly produced an online special featuring his cover art over the years, entitled Cover Story: Jean-Jacques Sempé’s Dancers.

His work on the New Yorker meant a lot to him, as relayed by Charles McGrath in the 2006 NYT interview:

“Taking out a little card, he drew, from left to right, three progressively larger circles connected by horizontal lines. They represented three stages of his life, he explained: Bordeaux, where he was born; Paris, where he moved in the ’50s; and New York, where he realized a lifelong dream in the late ’70s, when he began to publish in The New Yorker, which continues to feature his covers and drawings.”

In the early ‘60s he started publishing collections of his work with Éditions Denoël. At a rate of a new collection almost every year (although later years they became more spaced out) – from 1961’s Rien n’est simple (‘Nothing is Simple’) to 2009’s Sempé à New York (‘Sempé in New York’) – there are at least 29 of these albums in existence with a number of specials that could be added to the count.

RIP Jean-Jacques Sempe. Most beautiful line and gentlest humour of any cartoonist. pic.twitter.com/JPt6OGOn9C

— Jon “Semi-Fungible Airships” Kudelka (@jonkudelka) August 11, 2022

His work has appeared in numerous exhibitions and he had been awarded the city of Bordeaux’s Grand Prize for Literature (1987), the Alphonse-Allais literary prize (2003) and Germany’s eoplauen Preis lifetime achievement award (2008). In 2006 he was decorated by the French Ministry of Culture with the rank of Commander in the Order of Arts and Letters.

His understated yet expansive – and expressive – style impressed many and drew him acclaim, helped make the adventures of a little boy a beloved piece of French culture, and his cartoons were so distinctive that it bought joy and enthused the observer.

Francis Marmande at Le Monde:

“Sempé was a cartoonist. But more than just a cartoonist. He was able to analyze, to make people laugh, excite them, show them what they had never seen before and change the way they look at things. He captured the language of the age, recorded its images and offered as much food for thought as Georges Perec (Things), Pierre Bourdieu (Distinction) and Roland Barthes (Mythologies). With a bonus burst of laughter. He had a certain touch, a sense of “reported conversation” above and beyond the best satires. He was the philosopher of cartoonists.”