Tijuana-based artist Charles Glaubitz’s work has appeared in art galleries and museums all over Mexico, the U.S., and Europe, and his illustration and graphic design work has won him clients and accolades, but it’s only recently that he started doing comics, despite the fact that he’s loved the form since he was a kid.

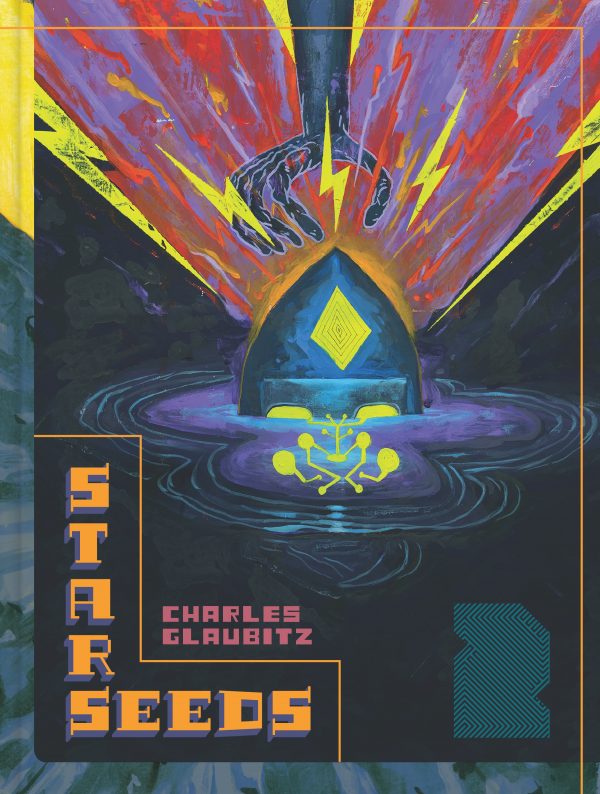

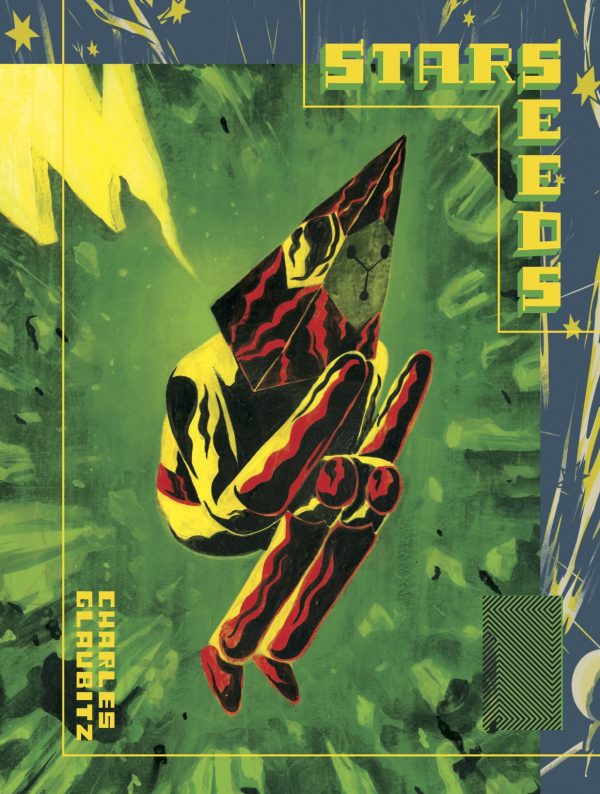

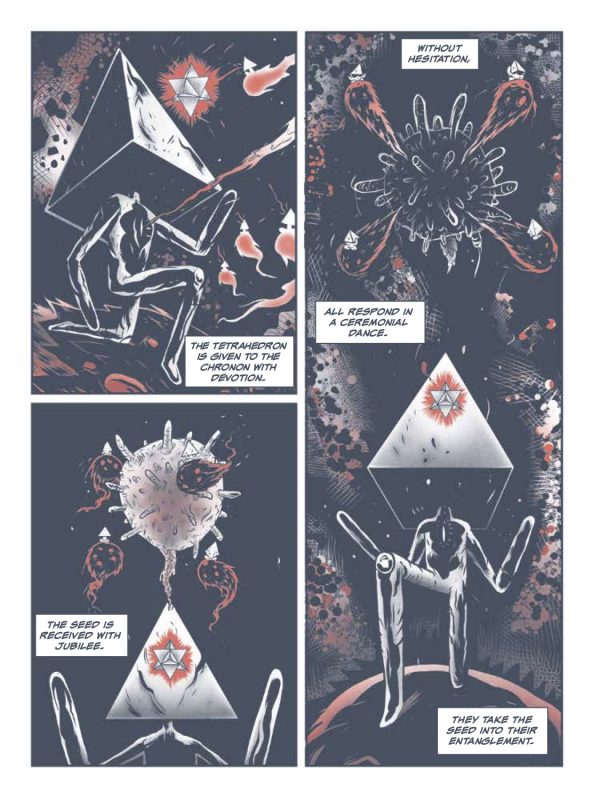

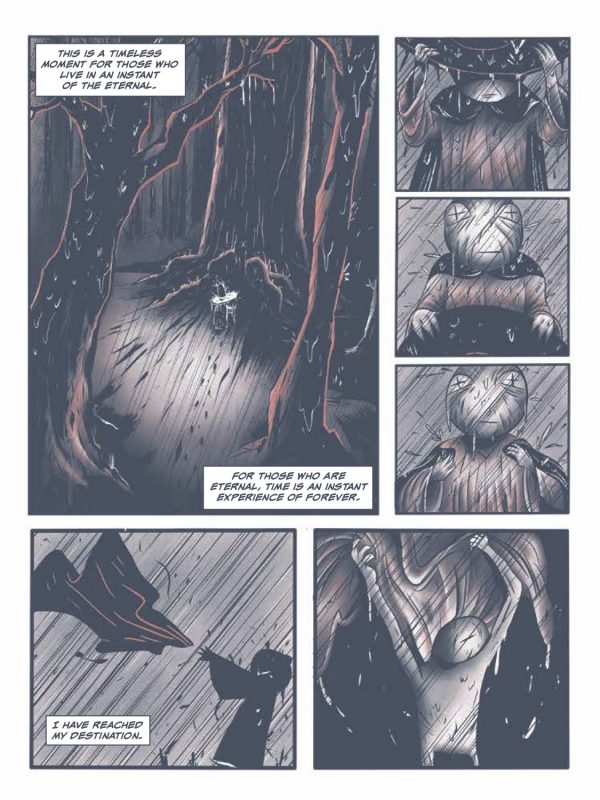

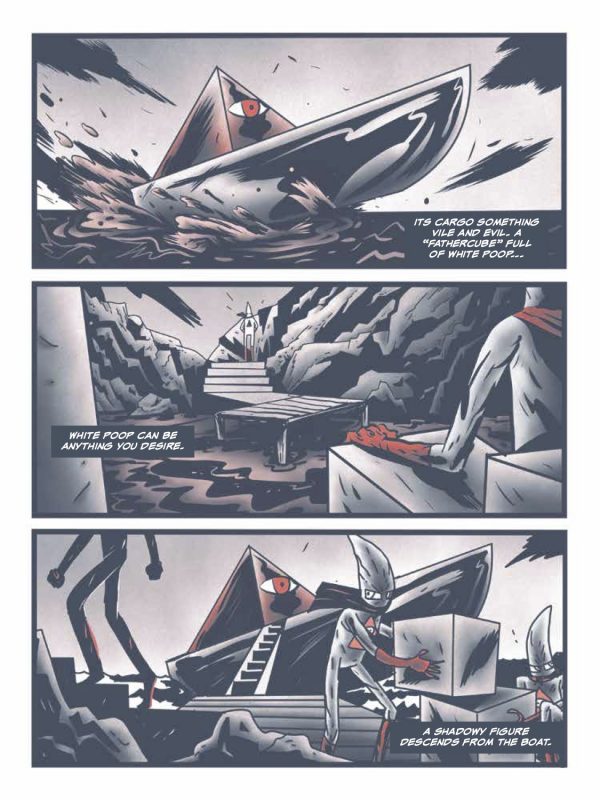

Starseeds was released by Fantagraphics in 2017 and now, two years later, its follow-up Starseeds 2 has hit the shelves. Glaubitz’s graphic novels are defined by their frenetic psychedelia as they seek to portray an entirely new cosmology built around a number of modern fringe beliefs. It’s both a satire and a tribute to outlandish beliefs at the same time, informed in Glaubitz’s fascination with the fringe and his personal art practice and goals.

When we began our conversation, the first order of business what to find out how such a sprawling, dense, kinetic work was even conceived.

_______________________________

I was very curious about the origins of the graphic novel in the context of your artwork because, if I understand it correctly, you created paintings that were called Starseeds that the graphic novel grew out of.

You got that right. I wanted to make art and I wanted to make art that had to do with my interests — comics, animation — and the idea was to make a series of paintings for gallery shows where it would tell this huge narrative, this new modern myth, and people would go to the shows to follow it. Each show would be a chapter. So they’d go to the show to follow a new chapter in the evolving story narrative. But it never really took off, so I ended up with a lot of story, and I always found myself explaining what was happening since paintings are a fragmented idea of a larger whole. So I just decided, well, what if I use each painting as a key moment and then narrate the in-betweens from key moment to key moment. The narrative started from there.

So you didn’t have strict narratives to start with. Could you qualify the paintings as an outline of your ideas?

They are the main plot. Each painting is like a main plot point. I kept pulling fragments of this larger idea that I wanted to tell at the time that I probably didn’t have a capacity to do, or the understanding that narrative without the in-betweens made me the narrator, or I had to fully explain what was happening. So it lent itself to work better as a graphic novel, as a comic, because the part that’s missing from the series and the shows was the part that I’m doing now, connecting the narrative in the comics.

You liked comics, but you didn’t originally perceive this as a comics project?

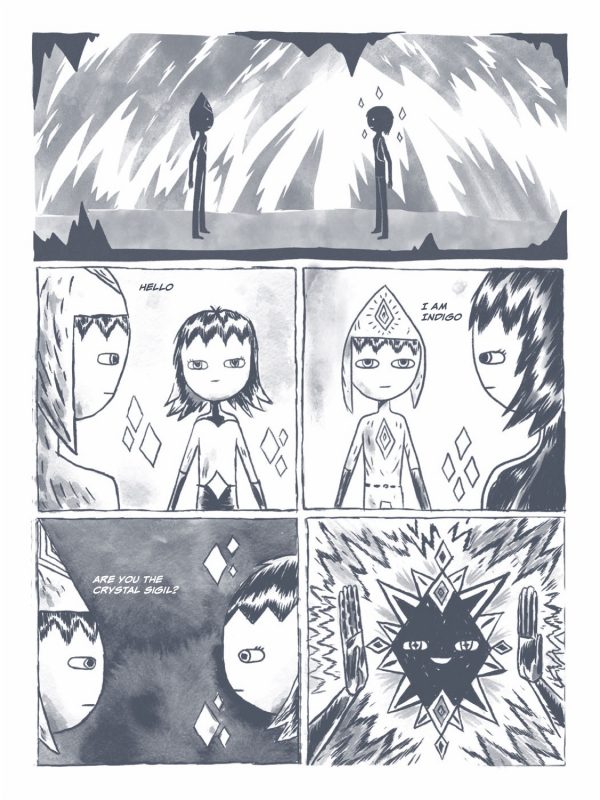

I’ve always been reading comics since I was a kid, but comics was like, in the art world, the lowest form of art. The idea was to take from that low brow influence and make that, I guess, highbrow in a way. But no, it wasn’t really the intent to make comics until around 2010 when I was invited to do a show in Mexico City, and I decided to do a linear narrative. Previously I was told never do a linear art narrative, that wouldn’t be considered art, that it would destroy the intent of fine art I guess. But I said, screw it. It’s called The Crystal Sigil, which is the first part of the first graphic novel Starseeds.

And I did so that it’s just image to image to image. And I think three-quarters of the way through it there was like 110 individual, 12 by 12 pieces and I had a realization that the reason I drew or I was interested in art or making art was because as a young kid I wanted to make comics. So I had this huge realization that all this time I did graphic design, I did the illustration, I did fine art, but I never did comics. And up to that point, I realized that that’s the original reason I draw and it kind of clicked from there.

What comics influenced your work in Starseeds?

Starseeds the idea at first started at Comic-Con. I went to a talk with Deepak Chopra and Grant Morrison, and they were talking about the Seven Laws of Superheroes and Grant Morrison was talking about the Joseph Campbell, and I’ve been a big fan of all of his writings. And he started talking about myth, mythology and, archetypes, and then an example was Jack Kirby’s New Gods, which at that time I hadn’t read. This was around 2005, 2006. I immediately grabbed a paperback copy, and I read it, and it blew my mind, this idea that the old beliefs and old gods were destroyed. And the Jack Kirby was attempting to create the new gods, obviously in the superhero tropes and mythology. But that to me just clicked.

From that moment on, I really liked Jack Kirby. I fell in love with his writing and his ideas and then slowly his art influenced me. I pretty much have anything he’s made post New Gods, but I haven’t read it all. I read Silver Star, and I have read the 2001 Treasury Edition. I have The Eternals, I have 2001: A Space Odyssey, but I haven’t sat down and read any of it. I guess I just clicked with his ideas or there’s a parallel between his cosmic work or we kind of say the same thing or something that’s really close and parallel together.

When I decided to make the first series of the work, I was really into Coast To Coast AM with George Noory. It opened me into this world of paranormal, pseudoscience, hermetic knowledge and Gnostic knowledge, quantum physics and whatnot.

I was looking for a prescient myth. What is society’s prescient myth? And it was, on the spiritual side, this new age belief of Indigo children, Crystal children, and Rainbow Children. And, back in the early, mid-2000s, the explosion of the idea that coincided with What The Bleep Do You Know and The Elegant Universe from PBS, and quantum physics and how that became more of a pervasive idea in our society. And I was like, okay, that hasn’t been touched upon. That’s something that could explain my feelings of alienation, of being, I guess, rebellious or punk or antisystem. Okay, so I could pick up on those ideas.

I think now I’m rebuilding something that is not told in the comic. And then it’s like, okay, what are the villains in this prescient myth? You search, and you get this Illuminati. And then what are the Illuminati and where does that idea come from? It comes from Robert Anton Wilson’s Illuminatus Trilogy. And then, okay, so it’s psychedelics, it’s like this trippy psychedelic world.

I could grab from what’s been created and then that led me to Zecharia Sitchin and the Anunnaki. So here I have these characters that exist in modern mythology that I can utilize to make a modern myth and, and create new metaphors of explaining what we’re going through as society or as the planet or as consciousness and combine that with my interest in quantum physics and put all of that stuff together and see what came out. So Starseeds came out of that.

Your comics have a cryptic quality. You don’t spell it out in plain narrative terms. You leave it to the reader to decipher and make connections.

I think one thing that I’m really not into in regular superhero comics was this necessity to explain everything. I think the reason I don’t explain is because it’s like a parallel metaphor to the mystery of our existence or the mystery of life or the mystery of this that we still haven’t figured out through science. But it has been attempted through mythology or through narrative and, and to try to make the reader figure it out for himself, for him to invest in the story, but at the same time project, consciously or unconsciously, onto the metaphors and archetypes of the story. So it’s, I don’t know, for them not to just sit down and be entertained, but more to be invested in it and for them to take what they can project onto it.

One thing that Joseph Campbell said, and this is a big influence why it’s not defined, is that, in order for it to be a living mythology it has to be open to transcendence, which is open to be interpreted, open to metaphor, open to poetry, to be interpreted constantly, for it to evolve. I think that’s my attempt.

How does that affect the backstories?

There’s a lot of backstory to it, but for whatever reason, I’ve chosen for it to just to be a story, for it just be a narrative, for it to explain certain things but not all things because then it becomes absolute narrative-wise and when that happens it gets closed off. And I’ve never been really into the idea that everything needs to be explained. I think that that has to do with my interest also in Japanese Manga comics or in French comics where there’s no necessity to explain the world, it’s just that’s the world, and that’s what happens.

What you’re describing seems the opposite of the prevailing method in popular entertainment now, where everything is fantasy or science fiction oriented, but also very, very spelled out. Creators like to world build and explain everything that happens. Perhaps a scenario is presented like a puzzle, but it’s puzzles to be solved with the answers eventually given. You’re really going against the grain by doing it the way you’re doing it.

I guess I never choose the easy path. It brings me back to this myth of the Knights of the Round Table, where I think it’s Percival and two other ones who I do not remember and they’re about to enter the dark forest, and there’s already paths, so the two chose two already walked paths. Percival decides, “I’m going to go through here, there is no path. I’ll make my own path because that’s the only way you can experience the dark forest – by your own experience or not anybody else’s experience,” if that makes any sense. It’s just this is how I’m choosing not to explain.

As you conceived of it and conceived at the visual style, did you have a lot worked out beforehand or was there a lot that you were working out as you worked on the original pieces and then graphic novel?

I would work on this series, and I would write down ideas of what was going on. Sometimes the ideas would come in images, and sometimes they would come in the written form, and I would I think in the beginning, early phases from 2007 to 2011, I was just constantly working out the narratives in my sketchbooks. I only had the paintings from the series, and The Crystal Sigil, which is the main story in the first Starseeds and then began developing other ideas.

The second story that was developing was the idea of the secret society, which was the Illuminati story. I was developing that by itself as a story. So when I presented this to Fantagraphics, they were just open for me to present something so I was like, okay, I’ll just grab these two stories and mash them together to see what happens and then what resonance happens within the story and what things shoot out that I could follow in the next story.

But then the next story Starseeds 2 is something that I had already worked out. So I don’t know, it’s just all these ideas are already prewritten out, and I’m just trying to find a way to make a narrative flow and find the way I would tell this story.

Do you have already thoughts of where it will go?

I have, yeah. I have 100 pages for the third book done. I have a whole series that I haven’t utilized, The Noosphere, which is the fourth book. And I have the plot points for the fifth and for the ending. Now the story itself is beginning to write itself, to tend to move towards certain areas that the story or the characters themselves need to be told in order for it to be alive. They’ve already started having a life of their own. So it’s like, okay, this character has to go through this or has to say this and has to experience this by the time he gets to the ending. It’s written out, and it’s beginning to write itself out at the same time

And it’s taking on an epic proportion that’s fitting of the subject matter.

I think at the beginning I had said it’s a 1500 page story. It’s something that’s an epic. I love epics. I love long stories, something that takes you years to produce. And you read it because it takes time to produce the story, it could be a year or year and a half between one book to another book, but you don’t lose the essence or the experience of reading the previous book before you get to the next book. J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter did that to me. It’s like I could just wait until I say, okay, it’s coming out next year. I can’t wait to get my hands on it, and then I would get my hands on it, and I was set, I don’t know, four or five days, to not do anything but read.

I like those kinds of stories. I like those epic stories. And it’s a parallel to old mythologies. It’s parallel to the Bhagavad Gita, the Bible, the Mayan Aztec Codex, something that’s large as it evolved to tell an epic story,

Starseeds does definitely have that quality of an older religious text, with little stories that have bigger implications on the universal order.

And those cycles from the narrative begin to parallel cycles in life or cycles in life as the story evolves. So it’s like we all live in cycles. We are cyclical in meaning from beginning to end to beginning again. So those little actions or sequences or chapters lead to more actions or sequences or chapters as the story evolves.

Starseeds is a work I imagine people reading multiple times.

I think going back to the idea that a myth that should be open to transcendence so by not making it the absolute in what it means, it’s open to be re-read, be seen again. I think another influence on that is Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo. I saw it for the first time 15, 20 years ago, and then I saw it, I don’t know, five years ago. So it has a different meaning to it even though the film, the story or the narrative, is the same. But since it’s so open to be interpreted, you experience it differently.

A creative work becomes as much a reflection of who you are when you approached it as who the creator was when it was made.

That’s what I think I’m striving for. Obviously, I’m the creator, but it’s not about me, it’s not about my experience of the story, but for it to be universal and for it to be experienced in an individual way. Individuals are different so it could have so many different readings or ways of perceiving it and that’s a big interest because that is reality. That is how we perceive reality. It’s defined by individual experiences and then individual experiences make up that whole experience, that unified view, which is, I guess you would call it multiple dimensions, just basically in people’s minds or how we experience reality.