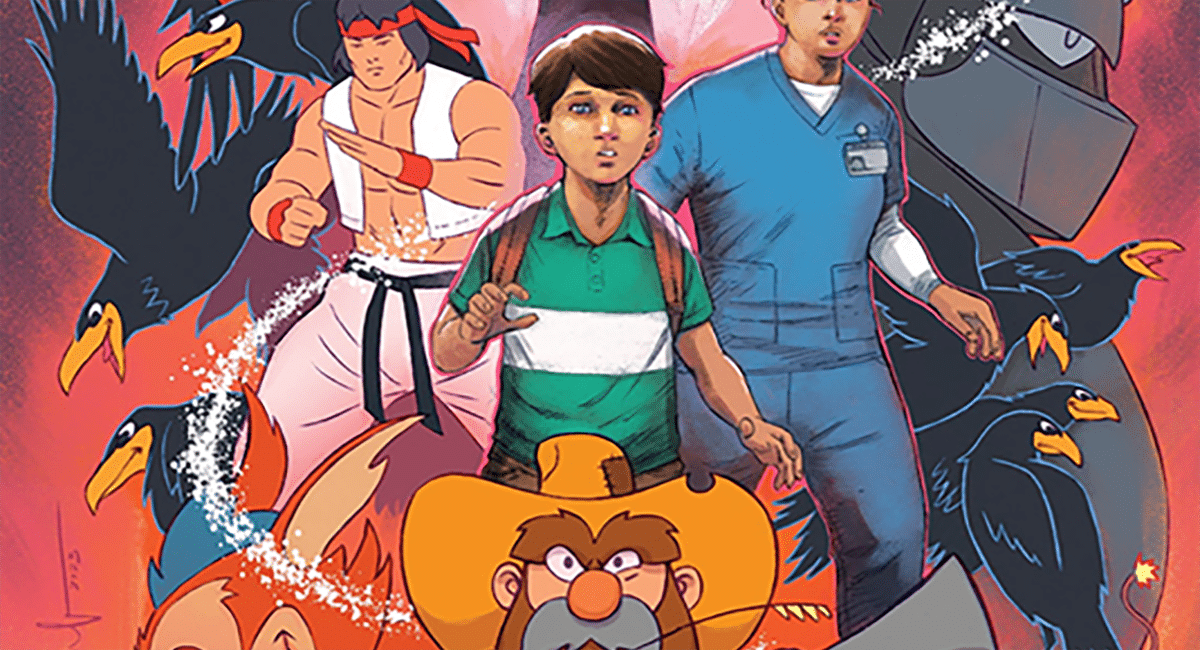

Robin Ha‘s Almost American Girl made The Beat’s list of anticipated winter graphic novels for good reason: it covers the sensitive subjects of immigration, single parenting and bullying with brutal honesty. Robin’s new graphic novel is accessible, relevant, and offers a fresh and unique perspective of the challenges adolescents face as they carve out an identity in the harshest of environments: the American classroom.

The Beat talked to Ha about Almost American Girl, the challenges she faced as an immigrant and the role that comics played in helping her adapt to her new country.

Nancy Powell: Congratulations on Almost American Girl! How does it feel having this story out for your readers?

Robin Ha: I am very excited to share my story with a wide audience, and I am very grateful that I was given this chance to talk about my experience. I hope my story will resonate with many people, whether they are immigrants or not. I hope it’ll give hope to people who are facing big challenges in their lives, that things will get better eventually if you keep putting one foot in front of the other.

Powell: How long did it take to complete Almost American Girl, from the initial story concept to publication?

Ha: I started working on this story in 2013. I took a one-year break to make Cook Korean!, and I finished the manuscript by the end of 2018. So it took about five years to make.

Powell: Why was this story important to you?

Ha: The year that I moved from Korea to America was probably the most difficult time of my life, and my life really changed completely after that year. So I wanted to write about it to understand why things happened the way it did, and how I was able to come out of it with a new identity of being a Korean American, which I now love and embrace.

Powell: Did the current political landscape influence your decision to write Almost American Girl?

Ha: I started working on this story during the Obama administration, and the immigrant stories in the memoir genre were getting a lot of attention and encouragement. I had no idea that a few years from then, I’d be seeing what I am seeing on the news now. I think the stories like mine really need to be told now more than ever before. I hope that my book can show that immigrants in this county face so many challenges everyday and that we are all human beings who experience the same emotions. We are not the monsters that certain politicians say we are.

Powell: Of all the states you could have settled in with your introduction to the United States, settling in Alabama must have felt like a fish out of the sea. What challenges did you find most difficult there, outside of language and culture?

Ha: I think my biggest challenge was the feeling of isolation and loneliness. There were no foreigners anywhere, and I felt like I stuck out everywhere I went. There were no Asian restaurants nearby. It was hard for me to get used to American food, which I found too greasy and bland. I also didn’t have any knowledge in American pop culture, so even when I did begin to speak English, I couldn’t bond with the other kids easily. This was why I was so excited to find the comics store where I could meet other kids who were into comics that I was familiar with.

Powell: As an American-born Asian growing up in the seventies and eighties, I often found myself hiding the things that made me different from classmates. Was that your experience as well?

Ha: I knew pretty early on that no matter how long I lived in America, I would still have a bit of an accent when I speak in English, and I will never look like a white American person. So I decided to own my differences, and I picked and chose which part of American and Korean culture that I wanted to keep. The parts I chose to keep were the parts that I personally agreed with or liked, rather than feeling pressured to take on by society. I don’t think I had the ‘Twinkie’ phase that many Asian Americans go through. I went straight from F.O.B. to bonafide Korean American. It was an easier way to spend my energy, to make my difference as an ‘asset’ that other Americans didn’t have, rather than thinking of it as something shameful that I needed to hide. But I am sure my situation would have been different if I were to have immigrated in the 70’s or 80’s when Asian immigrants were fewer and they faced a lot more discrimination than the current era.

Powell: It must have been a challenge for your mother to maintain tradition in this new environment. How important was it for your mom to keep you grounded in Korean culture while simultaneously trying to assimilate to a new language and culture?

Ha: My mother didn’t like the Korean traditional family customs and finally had to run away to get out of it. Therefore, she never forced me to follow the Korean traditional way of living. I am a 38-year old, unmarried and without kids. In Korea, people would think something must be wrong with me. But my mother never nagged me on when I’ll be getting married and have grand kids for her to play with. She just let me be the way I am, which I am very grateful for. She and I are pretty unconventional Koreans in many ways, but the one thing that she had instilled in me about Korean culture was the food. Korean food is something that my mom and I share the most time talking about and making and eating together.

Powell: What were the biggest changes in moving from Alabama to Virginia?

Ha: Northern Virginia is one of the most diverse places to live in the United States. So just the number of immigrants that I saw everyday in school and everywhere I went made a huge difference in how I felt about living in America. My mother and I settled near a big Korean town, and I was able to eat Korean food everyday and make lots of Korean American friends. It made me feel a lot less lonely. I was happy to see that many different immigrant communities had made a permanent home and were thriving here.

Powell: And what things stayed the same between the two environments?

Ha: Other than the fact people spoke the same language (English), and some of the suburban architectures and chain stores looked the same, I think everything else had changed when I moved to NoVa.

Powell: Can you talk about the role that comics played in helping you adjust to your new surroundings as an immigrant?

Ha: I was a huge fan of comics when I was living in Korea, but I read only Korean comics (manhwa) and Japanese comics (manga). When I moved to the states, manga was just becoming popular in the states, and many kids were getting into it. It was the only thing that I found in common that I could talk about with the kids around me. I was amazed that American kids found the same comics that I was reading enjoyable, and their excitement in reading those comics were exactly the same as mine. Comics was the umbilical cord that connected both worlds to me. I don’t think it would have been possible for me to make friends that I really connected with in Alabama without comics.

Powell: What was the earliest comic you ever drew?

Ha: I don’t remember the very first comics that I had made, but I drew a comic called ‘Fantasia’ when I took a comic-book making class back in Alabama when I was 14. It was a total rip off of all the Korean and Japanese girl’s comics I was reading back in the days, but it was the first comic longer than 10 pages that I had actually completed. I even got to sell it as a mini comics at the comic book store.

Powell: What comics influenced you the most as a teenager?

Ha: I was a huge fan of Korean and Japanese comics that came out in the 70’s, 80’s and 90’s. My favorite authors were Shin Ill-Sook (Lineage), Won Soo-yeon (Full House) Lee Mi-ra (Land of Silver Rain), Ikeda Riyoko (The Rose of Versaille), and CLAMP (X, Tokyo Babylon).

Powell: What comics have played a pivotal role in your development as an artist?

The comics I’ve mentioned above got me into comics, then I went to RISD (Rhode Island School of Design) to study illustration, I was introduced to many American and European comics there. It’s hard to name all the comics that have influenced me as an artist because there are too many, and it’s always changing. But to name a few, I loved the Sandman series and comics by David Mazzucchelli and Mike Mignola, and French cartoonists such as Mobius and Kerascoet.

Powell: My first experience cooking Korean food came from Cook Korean! How hard was it to illustrate the recipes in the book? Did you draw from photographs you took, or did you draw from a still life composition of the dishes?

Ha: I am so glad to hear that you are cooking Korean food at home, and my book helped you to try it! As you said, I took several photos as I was cooking and used those as references. I always took photos of the finished dish, so I can paint them in detail for the chapter covers which were done in watercolor. Drawing the recipe comic came naturally to me. It made sense to me that cooking can be taught through comics maybe because I had read other comics back in Korea which were educational comics.

Powell: Will there be a second volume to Cook Korean! based on recipes you publish on your blog, “Banchan in 2 Pages”?

Ha: I love to cook, and I have a lot more recipes that I would like to share with an audience. So yes, I would definitely like to make another comic-book cookbook in the future.

Powell: If you could give your 14-year old self advice in Almost American Girl on how to survive moving to a new country, what would that be?

Ha: I’d say, ‘be more patient with yourself, and stop caring so much about how other people might see you or think about you.’ The best part of being older is that you care less about what other people think, so you can concentrate more on what you really want. I also wish I could have told my 14-year old self that you are doing fine and things will get better before you know it. But I know that if an adult had told me that then, I wouldn’t have believed it anyway. These words can only truly make sense if you have gone through it yourself.

Check out Robin talking about Almost American Girl below.