by Alex Dueben

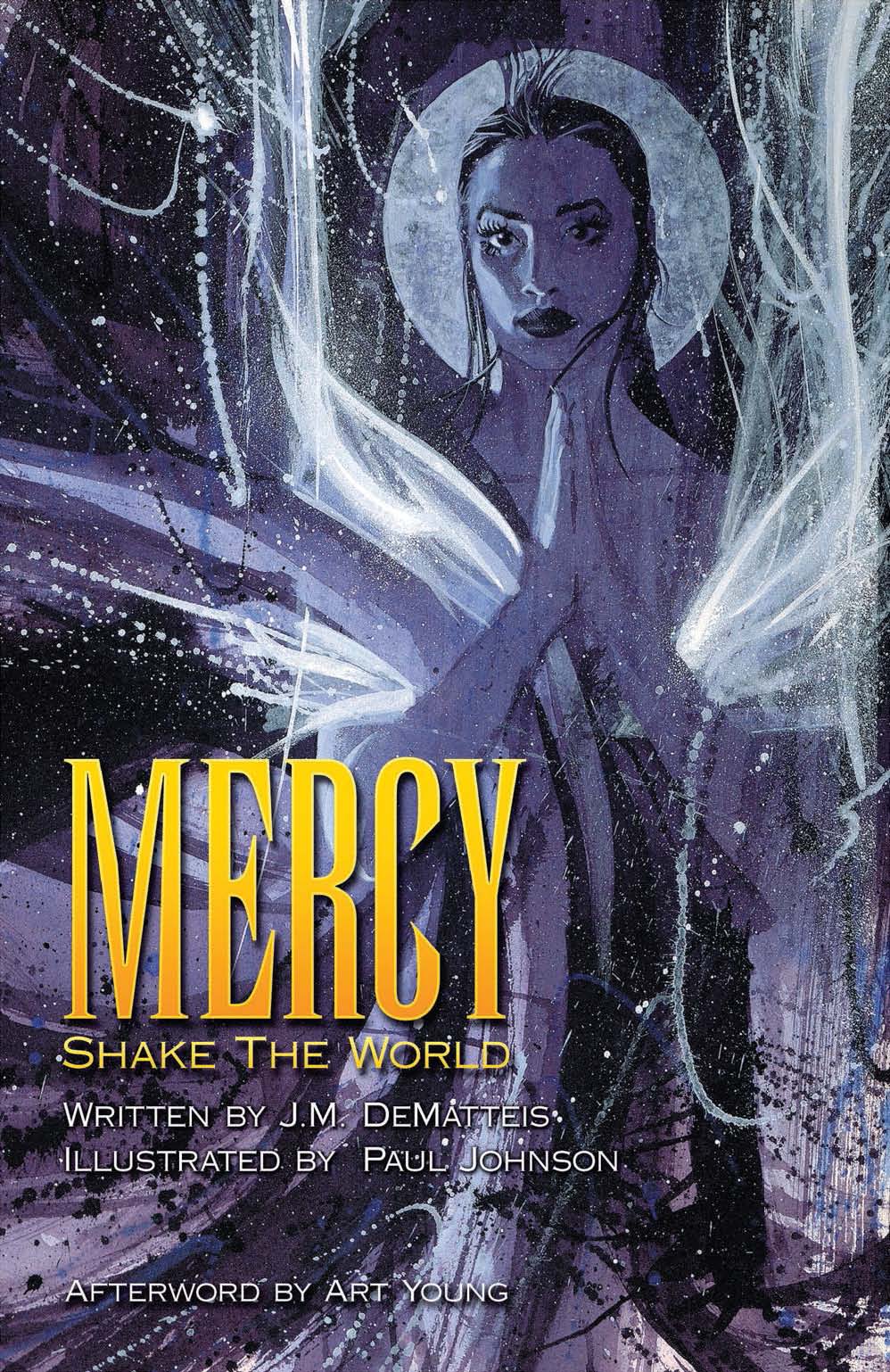

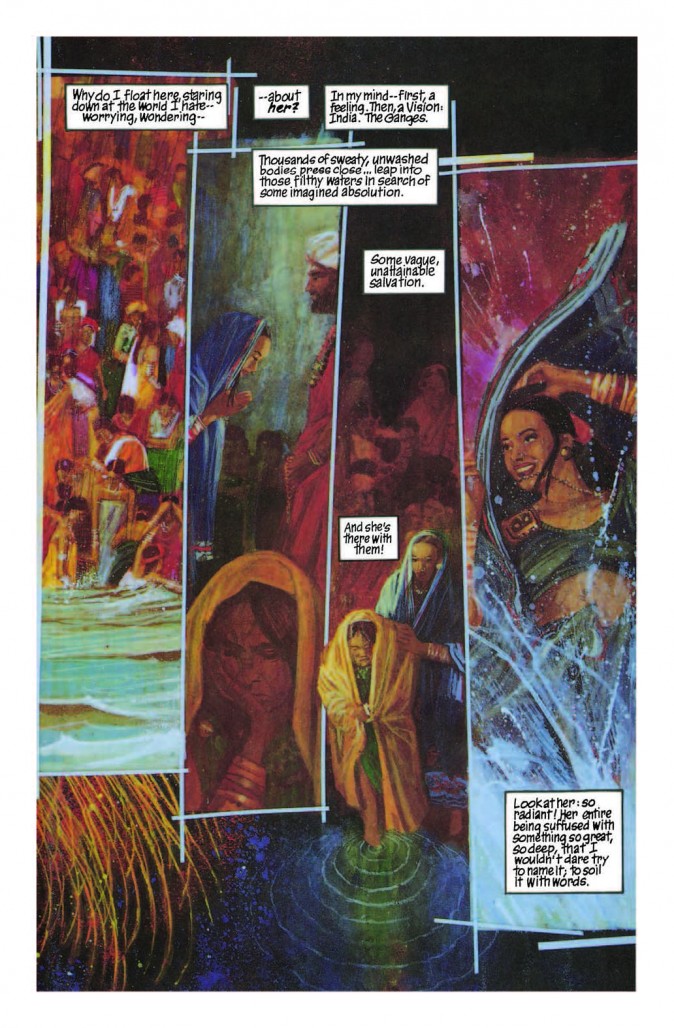

Paul Johnson worked in comics for a relatively short time, but during those years, the British artist and painter worked with some of the most talented writers in comics. His collaborators included Neil Gaiman (Books of Magic), James Robinson (London’s Dark, Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight), Grant Morrison (The Invisibles), Steve Moore (Tales of Telguuth), Pat Mills (Flashback 2099: The Return of Rico), Peter Milligan (Aliens: Sacrifice), Dan Abnett (Sinister Dexter) and Nick Abadzis (Children of the Voyager). Dover recently published a new edition of Mercy, a book by J.M. DeMatteis and Johnson that was developed as part of the never-launched Disney Touchmark line and published as one of the titles that launched DC’s Vertigo imprint in 1993. Johnson recently spoke to The Beat about Mercy— which he called one of his favorite works— how he came to comics, and why he left it behind.

Alex Dueben: Did you know J.M. DeMatteis and his work before working on Mercy?

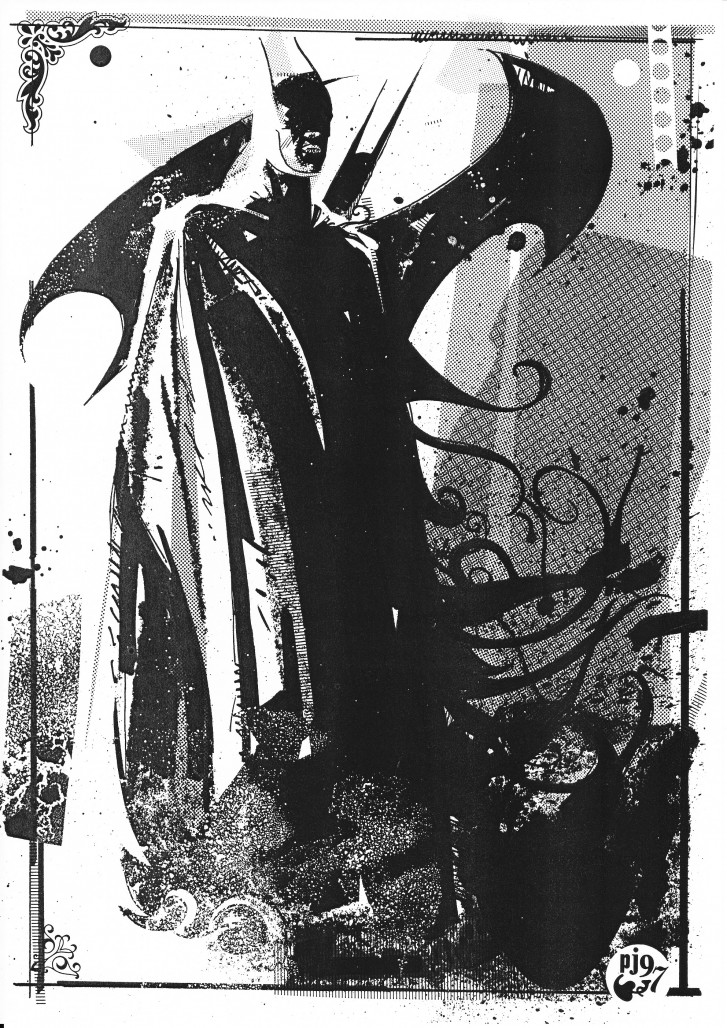

Paul Johnson: I’d never met Marc before collaborating with him on Mercy. I was aware of his work, however, which made me eager to work with him. Blood had come out and was radically different compared to most of the other stuff at the time. Not only did it look great, but it also had an unusual storyline. When I fell into drawing comics, I tended to want to do things that were a little left-field. I never had the intention of drawing anything mainstream, although I did end up drawing Batman in three issue of Batman: Legends Of The Dark Knight, which was fun. I was very interested in European bande dessinée, which had a much wider scope of storyline than DC and Marvel comics, and I was hoping I could do something like that but for the American market.

Dueben: What was the process like? There are script pages included in the new edition of Mercy where DeMatteis just outlines the story. Did you have that much freedom as far as laying it out?

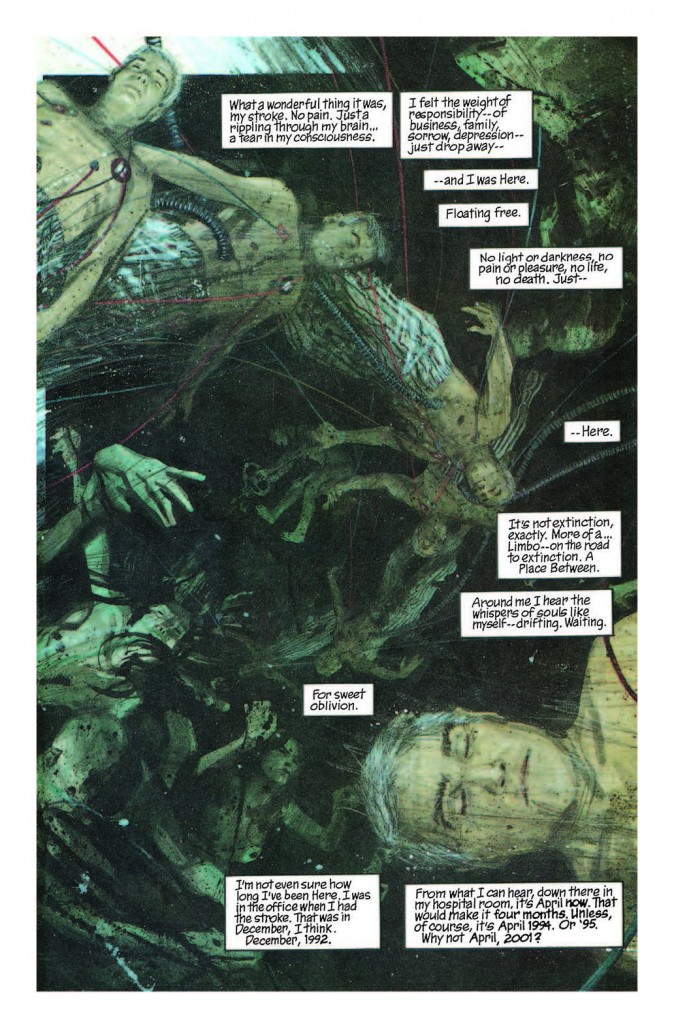

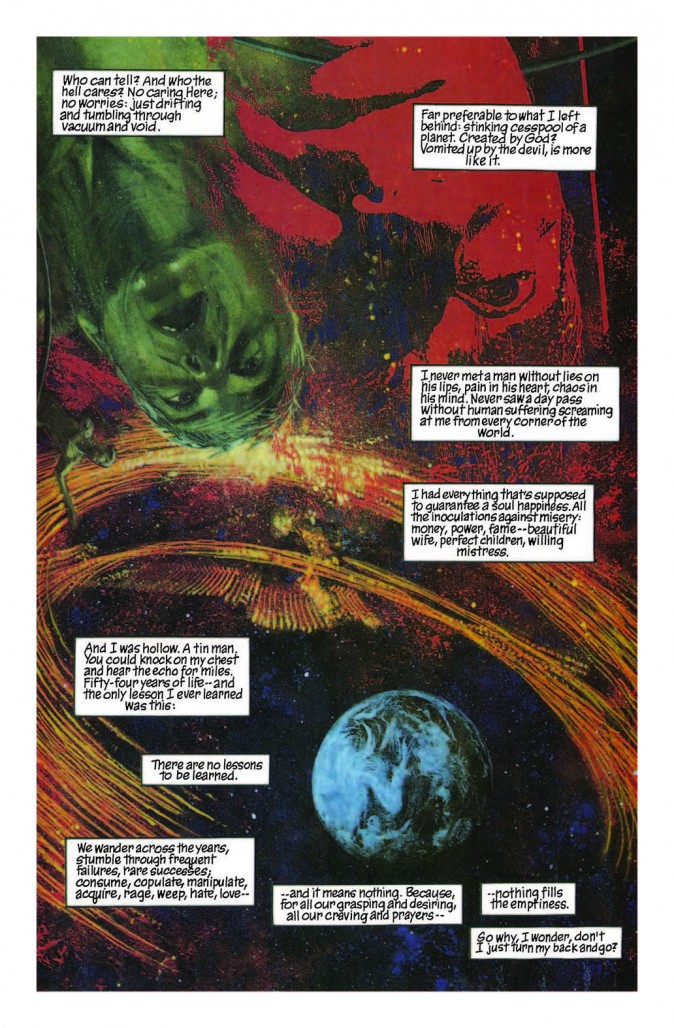

Johnson: Marc was great, he gave me as much space as possible to do my thing. I really enjoy the classic Marvel approach where the writer provides the outline and the artist creates the graphics. The writer may have a very clear idea about what they want on the page, but comics work best as a collaborative affair. As an artist, I wanted to be free to play around with the way the story was being told in order to put the emotional accents in the right place — slow it down here, speed it up there, etc. Exploring ways to express the narrative was key for me. I didn’t want to have panel after panel of waist-up figures with huge word balloons above them!

There was quite an explosion in storytelling techniques in American comics at that time. Will Eisner had pushed the art form to its limit in The Spirit in the Forties, but a lot of his techniques had fallen by the wayside. Artists in the Eighties and Nineties became very interested in picking up those techniques again to support the emotional content of their stories.

Dueben: You mentioned that this is one of your favorite projects. What made it so special for you?

Johnson: I had become enamored with European comics and a bit disenchanted with American strips. As a result I tended to work on projects that were on the edge of mainstream comics. Even the Aliens project I did for Dark Horse, Alien Sacrifice, was unusual as you hardly saw the monster in the entire strip! Mercy was a chance to move away from the typical projects I was doing at the time. I was being offered a lot of horror projects, which I found easy to do but I didn’t particularly enjoy. I wanted something positive, something that spoke about joy, understanding, and compassion. And along came Mercy.

Dueben: You went to art school, and I’m curious about the influence of fine art and the influence of comics on your art and how you try to merge the schools in your work.

Johnson: I started copying comic book art when I was 13 —mostly Marvel characters, actually, from the artists I admired like Jack Kirby, Gil Kane, Barry Smith, Paul Gulacy — and decided I really wanted to draw comics for a living. Now of course that wasn’t a career opportunity then – virtually nobody did that kind of thing for a living. It certainly wasn’t the big business that it has become now!

When I finished school I did a one year foundation art course. I had assumed that after that I would go on the study graphic design, but to be honest I found those classes really dull, whereas I found the fine art drawing and painting classes really inspiring. So when I chose a degree to do, I chose fine art. I really threw myself into my studies at that point. I still drew some comics to amuse myself (and try and make some money!) but the two sides of my art were very separate then. After graduating from college I bummed around in various jobs and ended up in an art studio producing training material.

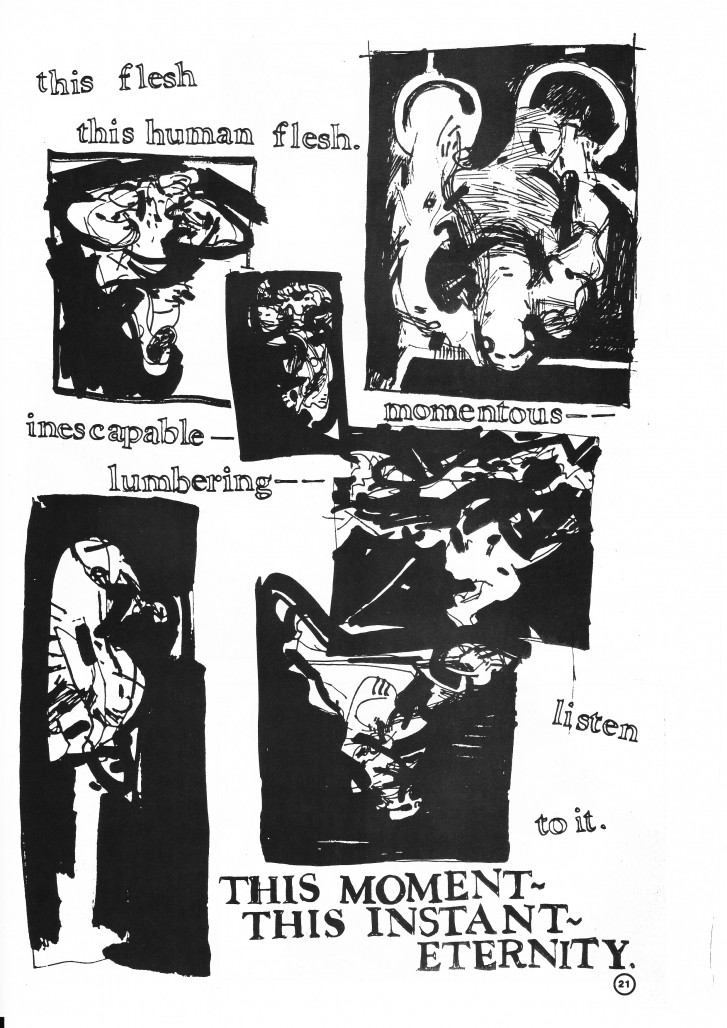

It was during this time that I started to mix ideas about comics and contemporary art. I started to play with storytelling formats and experiment with different illustrational techniques. I produced strips where the images were manipulated and distorted by repeating photocopying. I drew four foot high comics in charcoal. I drew Marvel-style punch-ups between abstracted cubist characters. I layered images from different stories over each other so that as you read the strip you were moving between different (yet linked) concepts. Raw had started in 1980 and showed that comics could be liberated from a constrained format. I started to look at the experimental comics produced in Europe and started to self-publish my strips and sell them through art galleries such as the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London.

I wasn’t really thinking about working for DC or Marvel, although I could see that artists like Bill Sienkiewicz and John J Muth were happily mixing lots of different techniques and styles in their comics. I knew James Robinson at that time, and he was desperate to break into comics so we started work on the project that became London’s Dark after seeing Gaiman and McKean’s Violent Cases. I sent some work off to Archie Goodwin, who was working at the Marvel Epic imprint at that time, and he offered me work on a relaunched version of Hudnall and Lloyd’s Espers called Interface. At that point, full-colour printing was becoming much cheaper and comics companies were looking for people who could produce fully painted artwork. I happened to be in the right place at the right time!

My comic painting technique and style drew on a wide range of influences from fine artists such as Rembrandt, Degas and Francis Bacon to classic American illustrators such as Howard Pyle and N.C. Wyeth. When I started working professionally on comic strips I really wanted to keep myself engaged with different techniques whilst still telling an intelligible story. Unfortunately, some of the painters moving into comics at that time would produce exquisite images at the expense of the story. You wouldn’t have a clue what was going on!

Dueben: I am curious what it was like back in the Eighties and Nineties as you were starting out and painting these comics. Was there a lot of energy and enthusiasm for this new approach to comics? What was it like?

Johnson: The Eighties and Nineties were an exciting time in comics generally. To understand this you need to appreciate what the scene was like in the Sixties and Seventies. Comics were dominated by the big two, D.C. and Marvel. Certainly in the UK, where I live, it was hard to get any American comics by other companies. When Heavy Metal came out in 1977, it was a revelation. Most of the strips were reprints from the French magazine Métal Hurlant and showed that comics could escape the superhero genre and cover all manner of subjects. The advent of the specialist comic book specialty store and the direct marketing of comics from publishers to retailers meant that companies like Eclipse, Pacific, and First were able to experiment with content and format in the late Seventies and early Eighties. It was a really exciting time and all the rules of comic books were there to be broken!

Alan Moore and Frank Miller pushed the envelope for mainstream comics, and this lead to much more off-the-wall material like Moore’s own (uncompleted) Big Numbers and Bill Sienkiewicz’s Stray Toasters. Suddenly it seemed like anything was possible! High quality printing was becoming cheaper and the idea of the graphic novel was being taken seriously. Creators and consumers were very open to a wide range of influences at the time, although of course there was some resistance from traditionalists such as Marvel Editor-in Chief Tom de Falco and his famously fruity outburst about Bill Sienkiewicz’s output (“I’m not going to print any more of this painted shit!”).

For a time, it really seemed like anything was possible in comics. To a large extent the mainstream comics were starting to dabble in what previously would have been in the independent or self-published market, something that the DC Vertigo imprint embodied in its early days.

Dueben: You mentioned that Violent Cases really prompted you and Robinson to make London’s Dark. What was it about Violent Cases that made such an impact?

Johnson: Really? You need to ask? I think it came out shortly after Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns. Those two projects has pushed the envelope for comic book heroes, but had essentially stayed within the genre, as had Electra: Assassin.

Violent Cases tore the envelope up with its storytelling. No lycra-clad heroes here. In fact, no heroes at all as I remember! Just an interesting narrative exploring perception and memory with exquisite art that showed there was so many ways to tell a story. You need to remember that this was a new way of working at the time. For me as a young British artist trying to get into comics, it was a Ground Zero event: everything before it was flattened, it was time to start again. I really hadn’t intended going into mainstream comics but that little book helped breathe life back into my enthusiasm. So when James Robinson and I started to discuss working on a project together we wanted to make sure we did something that didn’t fit neatly into any preset genre.

Dueben: You mentioned that you sent Archie Goodwin samples after you were working on London’s Dark and I assume you worked with him on LOTDK. Why did you target him and what was working with him like?

Johnson: It wasn’t so much that I targeted Archie but that he was in charge of sourcing the kind of work I wanted to do. He was Editor at the Epic imprint of Marvel at the time —although when I got to work with him he was already on his way out of the door to go to DC, so we didn’t do a lot together at that point. Epic was Marvel’s stab at the adult market, and they were using painted artwork. That’s where I wanted to be!

Archie really was such a gent. I cannot imagine anyone ever having a bad word to say about him. He was an astute character —intelligent, witty, dependable, honest – the perfect mentor. I think that pretty much everyone who worked for him saw him that way. When I delivered art for the first issue of Interface I was so disappointed by what I had done. Having to produce so much artwork in such a short space of time was a bit daunting. I felt that maybe I had let him down – that some of it could have been better. Archie was very straightforward – it wasn’t the best artwork he’d ever seen, but I was a professional and I would learn on the job. And he was right – each issue got easier to do and the artwork got better.

I remember the first time we met at a comic convention in the UK — he had seen samples I’d sent him — several fully-painted short stories on various adventure and science fiction themes. When I first introduced myself he was somewhat taken aback – I was in my late twenties whereas he had assumed I had been in the business for years and that the samples I had sent him had been of published work!

We got on very well. He was an honorary Brit really, spending a lot of time in the bar at conventions, always the last to go to bed, full of interesting conversation and wit. I remember him going to collect an award at one convention where he took a tumble on the stage – the audience gasped until they saw him leap back into the air. They hadn’t realized it was a gag!

I think it was Archie’s idea to use myself with James Robinson on LOTDK. James had already done a couple of projects with Archie and was getting great reviews. By that stage James was living in America, so the collaboration was all phone-calls and Fedex packages. It was great fun to do, but I always thought that my painted artwork was better than my black and white line- work.

Archie was a Zelig-type character, always there in the background. He had a fabulous career! His early work was drawn by legendary artists like Roy Krenkel and Al Williamson. He wrote all those great stories for Warren’s Creepy magazine and did editorial work on their other titles like Vampirella. He scripted the long running newspaper strip Secret Agent X-9. His Manhunter collaboration with Walt Simonson was a knockout at the time. He worked on Star Wars, Iron Man, The Fantastic Four, The Tomb of Dracula… he even created Luke Cage, the first African American superhero. He oversaw the American translation of Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira and much of Moebius’ work. Plus, he gave so much to the Batman mythology both as a writer and an editor.

I was shocked when I first saw Gary Oldman’s portrayal of Commissioner Gordon in the Batman movies. he looked so much like Archie! I wonder if anyone has ever told him that – that he looks like a writer/ editor so closely associated with that character? Archie died in 1988. He was only 60. What a loss.

Dueben: I did want to ask about two other Vertigo books you worked on. One is Books of Magic.

Johnson: Oh yes. That was my first project for DC. It was always envisaged as a four-part mini-series with each part drawn by a different artist. There was some revolving doors on the line-up. I think Dave McKean was down to do one issue, and a couple of other people. A lot of the British artists used to meet up at what was known as the SSI – the Society of Strip Illustrators – once a month. Neil and I had met previously so once again I happened to be at the right place at the right time and got offered the final instalment. How could I say no?

Neil wrote a well crafted script – tight enough to keep me on track but loose enough to let me play – just the way I like it. I’ve no idea if Neil liked the artwork or not – he was always a tough cookie to read. And he’s gone on to produce such great stuff!

I didn’t really fit in with the soon-to-be Vertigo mold of artist. I was crushingly shy —I had a terrible stammer in my childhood and dreaded any kind of public appearance so I didn’t do signings and didn’t really promote my work. Artists like Shaun Philips loved the limelight, they were very happy in front of a crowd. That was my worst nightmare. There was a Vertigo launch event at UKCAC (UK Comic Art Convention) where all the English artists working for the imprint got up on stage to answer questions. I stayed in the audience! Really, I never had any faith in my work, all I could see were its flaws.I always cringed when my comics came out —even stuff like Books Of Magic. I loved doing all those great double-page spreads and researching all of the old characters. I knew some of them from my childhood but some of them, like Mister E, were quite obscure.

It was a shame when the Books of Magic hardback edition came out because I still had some of the development artwork form my section knocking around. They used some of my really basic breakdowns when they could have printed some of my painted sketches.

Dueben: The other is The Invisibles, where you drew a couple issues. You had worked with Grant Morrison previously,right?

Johnson: Yes, I’d already collaborated with Grant Morrison on a Janus: PSI Division story for 2000AD. Grant often wrote stuff that was like lucid dreaming, and that was right up my street. Dream-like images, hauntings, telepathy, astral travelling, stuff that was fun to tackle. As I keep saying, I wasn’t really a mainstream artist. Although I did a Judge Dredd three-partner to tie in with the release of the Stallone movie, Janus was much more up my street.

So when The Invisibles came along it was easy to slot in to. There were some great moments in the issues I drew – I loved the touching scenes between Dane (Jack Frost) and his mum as much as the alien abduction scenes. Personally I think the second series of the book was by far the best.

I think we were all gutted when The Matrix came out. It has become clear now that many of the designers thought that the Wachowski brothers had the rights to The Invisibles as they were given copies of the comic and encouraged to base their ideas on it. Morpheus in the movies is such a ringer for King Mob! The BBC was developing a TV show based on The Invisibles but of course that got canned when the movie came out.

Work at Vertigo dried up for me at this point because Editor in Chief Karen Berger didn’t really like my illustrational style. I had some difficult conversations with editors telling me that they loved my work and they wanted to use me but they weren’t allowed to unless I changed the way I drew.

I went on to do some other Janus stories with Grant and then with Mark Millar, too, who was just starting out. All fully painted, all as whacky as hell!

Dueben: You did a number of stories for 2000 AD with various writers. Besides Morrison and Millar, you also worked with Pat Mills and Dan Abnett. Do you have a favorite among those?

Johnson: I am unusual amongst the UK artists who broke into the American scene in the Eighties in that I produced work for DC, Marvel, and Dark Horse before working for the home-grown market. 2000AD was a hotbed of creativity at that time, so I got to work with an amazing range of writers including Dan Abnett, Pat Mills, Steve Moore, Grant Morrison, Mark Millar, Pete Milligan, etc.

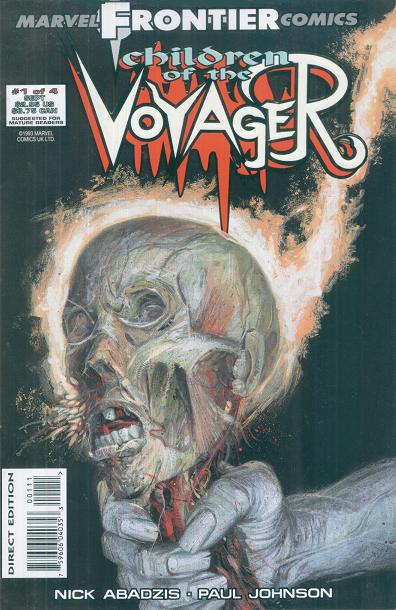

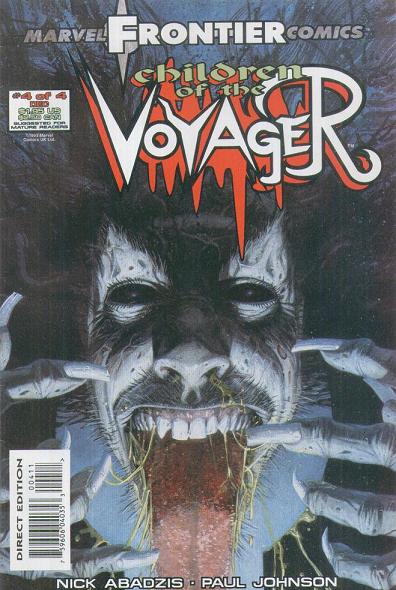

To be honest, my favourite collaborations were always with Nick Abadzis. I tended to stay away from the mainstream 2000AD characters and did a number of short stories. Nick Abadzis always wrote the most wonderfully outlandish strips that were a delight to illustrate! We also went on to create a four issue mini-series for Marvel UK called Children of the Voyager, which I would also dearly love to be made available again. Nick went on to win an Eisner in 2008 for Laika.

Dueben: Could you talk a little about working with Nick Abadzis. I know a lot of his work and a lot of your work, but I have to admit that I don’t know Children of the Voyager.

Johnson: Children of the Voyager was a four issue mini-series for Marvel UK. When we planned the thing we thought we were creating something that was going to be copyrighted to us, but it ended up belonging to them. Alongside Mercy it is the project I am most proud of. It was a four color comic with black and white artwork from me and the script and colors from Nick. I think it had the best line work I produced, atmospheric and edgy. The best I ever did. Nick wrote the story for me, so there were plenty of out of body experiences, witchcraft, supernatural beings and general mindfuck.

The basic premise of the story is that there are only a limited number of souls in existence, and as mankind has multiplied we’ve all ended up sharing bits of the same souls. The Voyager is a character who is rounding up these shards of souls when he meets Sam Wantling, a cheesy horror story writer who also happens to have part of a very powerful old soul that defies being hoovered up. Once again, it was an offbeat story, not really falling into any mainstream genres. It’s a story about fear, faith and redemption, about being willing to face up to your personal demons. I got to mess around with all kinds of panel layouts and textures in a way that you didn’t see in other Marvel UK comics.

It looks like it may see the light again at the beginning of 2016 as part of Marvel Frontier Comics: The Complete Collection TPB. Nothing has yet been confirmed, but I guess it will be appearing alongside all of the other titles that came out in that line. It will be nice to see it back in print, but it will be sandwiched between a load of superhero titles. I hope it doesn’t get lost — again!!

Dueben: Why did you end up leaving comics?

Johnson: To be honest, the explosion of possibilities I mentioned above seemed to dry up. The mainstream companies had their own properties and that’s what they wanted to sell. This era also saw the advent of cross-marketing of comics with computer games, movies, toys, etc. I had come into mainstream comics sideways, but I was still a bit of an outsider — too mainstream for the experimental comics and too experimental for mainstream comics. I had a great time drawing and painting comics when I did them, but I sensed the writing was on the wall and it was time for a change. I didn’t want to spend my time chasing and executing comics that I really wasn’t that buzzed about.

Dueben: Do you still paint?

Johnson: No, not really. I re-trained as an acupuncturist and herbalist and I now spend my time treating people from my private clinic or teaching in a London acupuncture college. I’m simply too busy to devote time to serious artwork besides the occasional hand-drawn Christmas or birthday card. I used to draw for my two sons but to be honest they weren’t that interested unless they had a friend round, and then it might be, “Dad, can you draw a samurai, can you draw a robot, can you draw a wizard?” in order to show off!

I fantasize that when I am older and have more time on my hands I may be able to devote myself to painting again. As far as comics go, I would only consider doing something if I thought it was going to be unique. I don’t know if I have that in me anymore!!

This guy was a terrific artist. I always wondered what happened to him. MERCY was a beautiful book and so was LONDON’S DARK. Now I have to track down that CHILDREN OF THE VOYAGER comic, as well. It’s a shame that he’s no longer drawing and that the business loses so many truly talented folks because they’re not adequately supported by the bean counters. Regardless, Paul seems like a very cool guy and it’s lovely that he’s had a second successful career as an acupuncturist/herbalist. Great interview.

Comments are closed.