Today, The Beat is pleased to present an interview between Arely Guzmán, Assistant Editor at Levine Querido, and translator King.

ARELY GUZMÁN: This is the kind of book where Taiwan is its own character. Having grown up in Taiwan during a very different time period from Kun-lin’s, what parts of Taiwanese culture were at the front of your mind when working on this translation?

LIN KING: I grew up in Taiwan in the 1990s and 2000s; martial law in Taiwan lifted in 1987, meaning I’m part of the first generation to not have lived under martial law at all. Taiwan in my mind has always been an open and liberal society where people are free to say whatever they want—a “beacon of democracy” and first government to legalize same-sex marriage in Asia.

But, unbeknownst to me, certain taboos were still in place even without official censorship laws, and I wasn’t taught in school about White Terror or the war with the Chinese Communist Party. It was only through family that I heard about Taiwan’s modern history: my maternal great-grandmother was a “Qing” woman who had bound feet; my maternal grandparents grew up as Japanese citizens; my mom was educated in the Kuomintang (KMT) system. The thing about Taiwan at the front of my mind when working on this translation was the fact these complete national, cultural, and linguistic overhauls all took place within the past century. I felt both awed and scared by how quickly things have changed and can change for Taiwan’s identity.

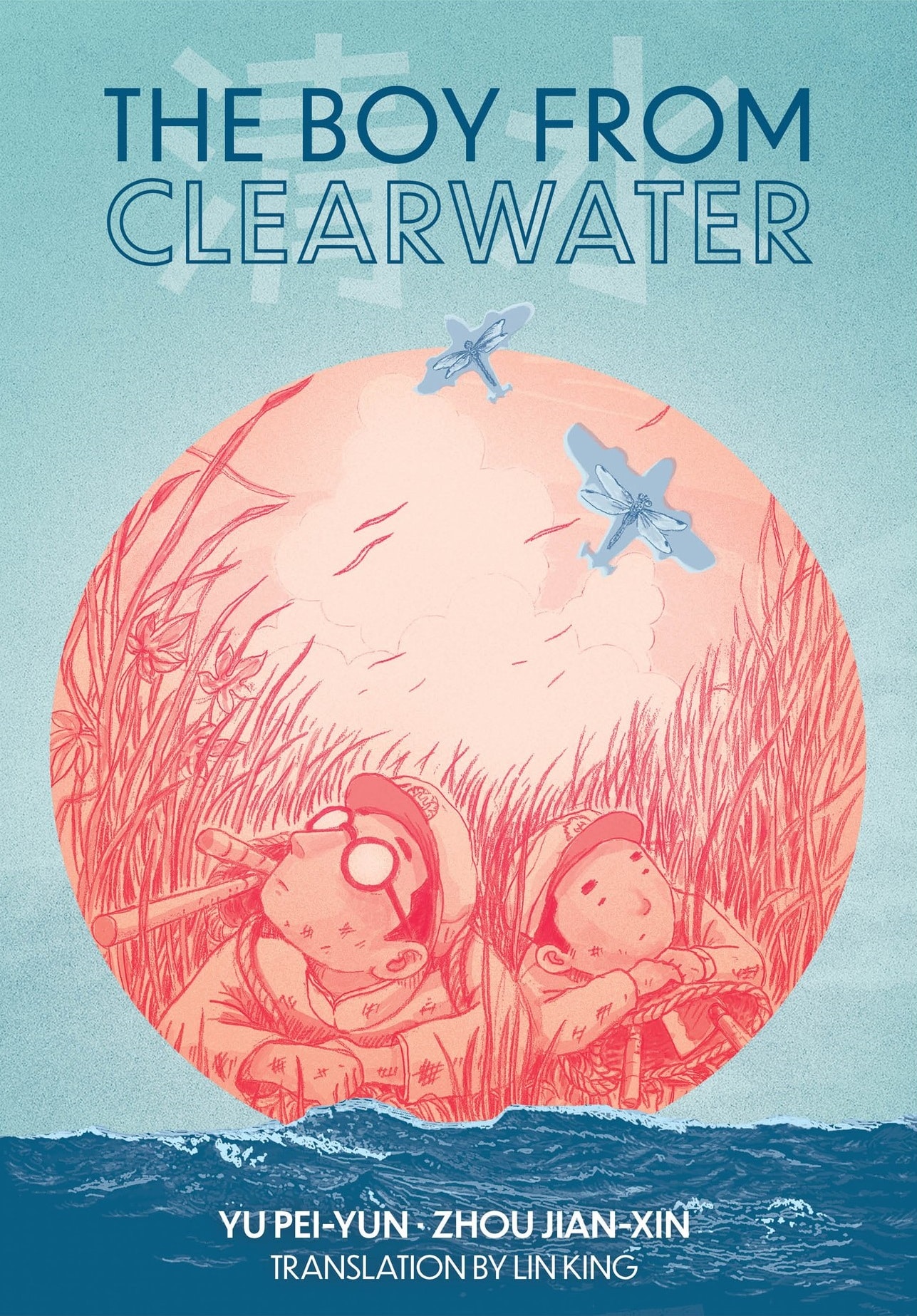

GUZMÁN: And what was it about The Boy from Clearwater that resonated with you? Why did you decide to––luckily for us–– take on this project?

KING: I didn’t know about the original book series until Levine Querido approached me with the project. I was amazed by the story of Mr. Tsai’s tumultuous and illustrious life—he was still living when I started on the project in fall 2022 and only passed away in fall 2023—and feel that his story is an incredible microcosm of Taiwan’s story over the past 90 years. The story is a heavy and complex one, but the striking artwork and carefully constructed text make it more accessible for a wider English audience.

GUZMÁN: You translated The Boy from Clearwater from not one, but three different languages––Hoklo Taiwanese, Mandarin Chinese, and Japanese! What was that experience like and how did you decide what to highlight from the different languages?

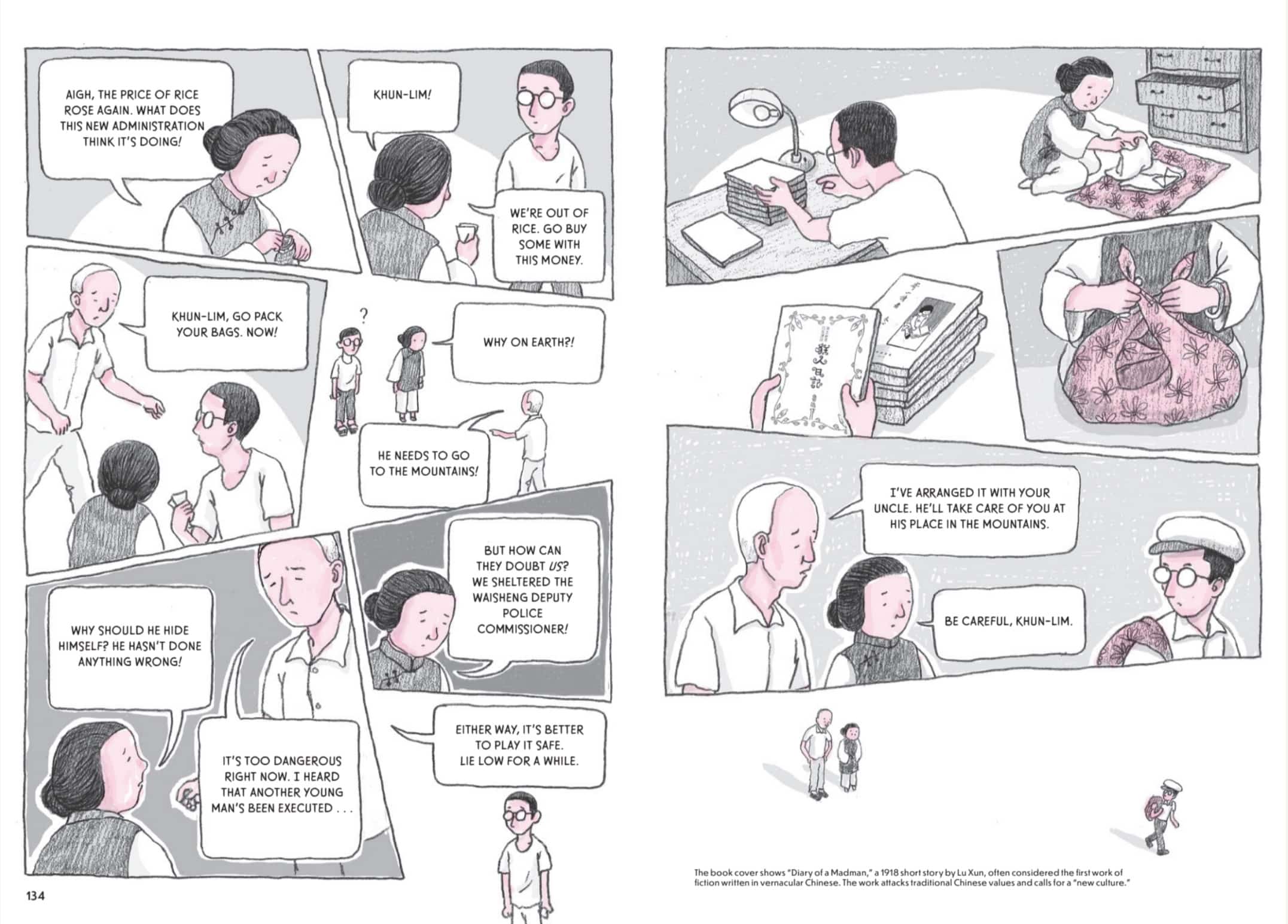

KING: Dr. Yu’s original text has Mandarin Chinese translations of both the Taiwanese and Japanese printed side-by-side whenever those languages were used. But I do know these languages, and so tried to translate directly from the “original” and showcase the differences between these languages when possible. For instance, there’s one part in Part 2 where Kun-lin and a fellow prisoner discusses the Japanese versus Chinese lyrics of a song, and I tried to highlight the subtle differences between the two to show how these overlapping layers of languages and ideas existed in Taiwan during this transitional period.

GUZMÁN: In your translator’s note, you mention that you chose the romanization systems according to the time periods and regions. Can you tell us a little bit more about how they informed these choices?

KING: As the note explains, while Mandarin, Japanese, and Taiwanese all share Han characters, they are pronounced very differently. In transliterating these words into English, I had to choose whether to stick to one romanization and make things easier for English readers (e.g. always using “Tsai Kun-lin” instead of also including his Taiwanese name “Tshua Khun-lim”), or to use Taiwanese pronunciation when characters are speaking Taiwanese, Japanese pronunciation when they’re speaking Japanese, and so on. The Levine Querido team and I ended up choosing the more complicated and more authentic option.

Romanization of Mandarin Chinese is a whole story in itself. It’s a bit of a pet peeve for me—I think, as a translator, I take it more personally than some other Taiwanese people. In summary, there have been many different systems of transliterating Mandarin Chinese into the Roman alphabet used over the years. The Hanyu Pinyin system, developed in China in the 1950s, is now the dominant system internationally, and even Taiwan officially adopted Hanyu Pinyin in the late 2000s. But many remnants of Taiwan’s earlier systems like the Wade-Giles are still in use, such as “Taipei” (instead of “Taibei” in Hanyu Pinyin) or President “Tsai Ing-wen” (instead of “Cai Yingwen”). Changing existing romanization for the sake of standardization is to me a form of erasure, and so I insisted on using “Chingshui” instead of “Qingshui,” among other proper nouns.

GUZMÁN: Your translation of Taiwan Travelogue is forthcoming, and from what I remember, you were working on both of these projects simultaneously. How was translating a graphic novel different from translating a prose novel?

KING: For both projects, I had to make a lot of similar decisions about transliteration. But Taiwan Travelogue is in some ways less complicated because it deals almost exclusively with the Japanese colonial period of Taiwanese history, whereas Clearwater is all about transitioning from one period to the next and to the next. Also, Taiwan Travelogue’s prose format meant that I could “stealth gloss” more, which is translation jargon for adding more contextual information around a term, e.g. “chawanmushi egg custard.” Clearwater’s graphic novel format meant that I had to consider whether the text would fit inside specific bubbles, which was another constraint and challenge.

GUZMÁN: Were there any unexpected challenges to working on this particular project? And how did you handle them?

KING: I spent quite a bit of time digging through historical English materials. If possible, I wanted to use existing translations of the various detention centers and laws for the sake of historical accuracy and English-language consistency. Some were really easy to find, and others took ages. I owe a lot to Levine Querido copyeditors, Columbia University’s C.V. Starr East Asian Library, and the National Human Rights Museum in Taiwan.

GUZMÁN: Something I remember having lots of back and forth conversations about were footnotes: which ones to leave, which ones to take out, which ones to add, and when to use them for in-art text. What was the process of making those choices like for you?

KING: All translation requires thinking about what information the reader will or won’t need, but the particular challenge of a graphic novel is trying to minimize the amount of “distracting” information on a page to avoid interfering with the visual effect of the amazing art. In that sense, I think you and I tried to be minimal with the footnotes, though with the mutual understanding that we didn’t want to sacrifice critical nuance. I don’t think we removed that many of the original footnotes—the one example that stands out is a footnote explaining what tap dancing is, which we agreed that English readers wouldn’t need.

GUZMÁN: While this story takes place decades ago, you are translating for a society that is currently experiencing book banning and censorship. How did this shape your translation?

KING: I think the societal context of book banning and censorship in the US and elsewhere made me a lot less willing to compromise on the linguistic and historical complexity of these books. There’s no direct cause-and-effect, but knowing that there are people out there trying to reduce the world into “simpler” strokes made me want to highlight how complicated the world is.

GUZMÁN: In Clearwater, you are immersing a largely monolingual audience into a multilingual society, but the everydayness of speaking multiple languages will be familiar to many American immigrant families. How did you envision talking to these different audiences?

KING: Speaking as a multilingual person who sometimes turns away from stories set in cultural environments that are unfamiliar to me because I feel too tired in the moment to do the mental labor, I can empathize with Americans—monolingual or multilingual—who might not want to deal with all these complexities while reading a comic. I hope the color-coding of different languages is a way to make readers constantly aware of these linguistic layers without forcing them to, say, check a glossary. Meanwhile, the different romanizations for the same names are a way to more explicitly challenge the readers and remind them of Taiwan’s specific languages.

GUZMÁN: Finally, what do you hope readers will be able to get from your translation of this text?

KING: I really hope readers will walk away with a better understanding of Taiwanese identity as something multilayered and multifaceted. The word “Taiwanese” encompasses being indigenous, or living under Japanese rule, or migrating from China after WWII, or pushing against an authoritarian regime in favor of a multi-party democracy, or so many other histories. Seeing all this, maybe readers would better understand why so many of us refuse to be identified by any word other than “Taiwanese.”

Something else that I think will resonate with a lot of English readers is how much work it takes to build and to sustain a democracy. This will be especially relevant in Volume 2, forthcoming in spring 2024. I think US and other readers will really be able to see the parallels of the effort that democracy requires, and how it’s worth the effort even given its flaws and fragility.

The Boy from Clearwater will be available from Levine Querido beginning on November 21.