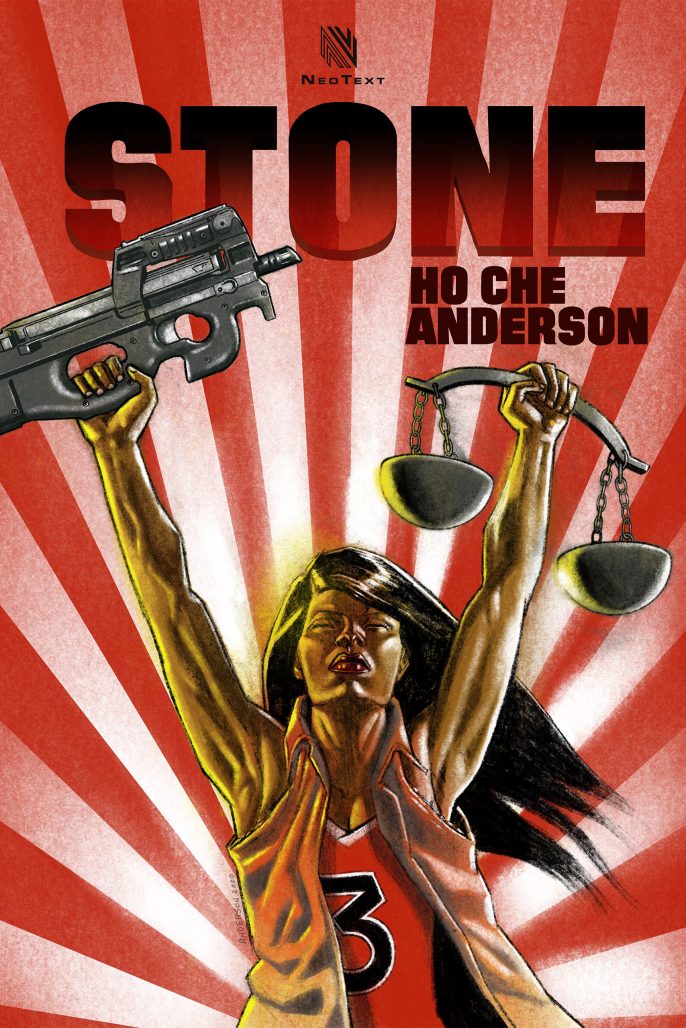

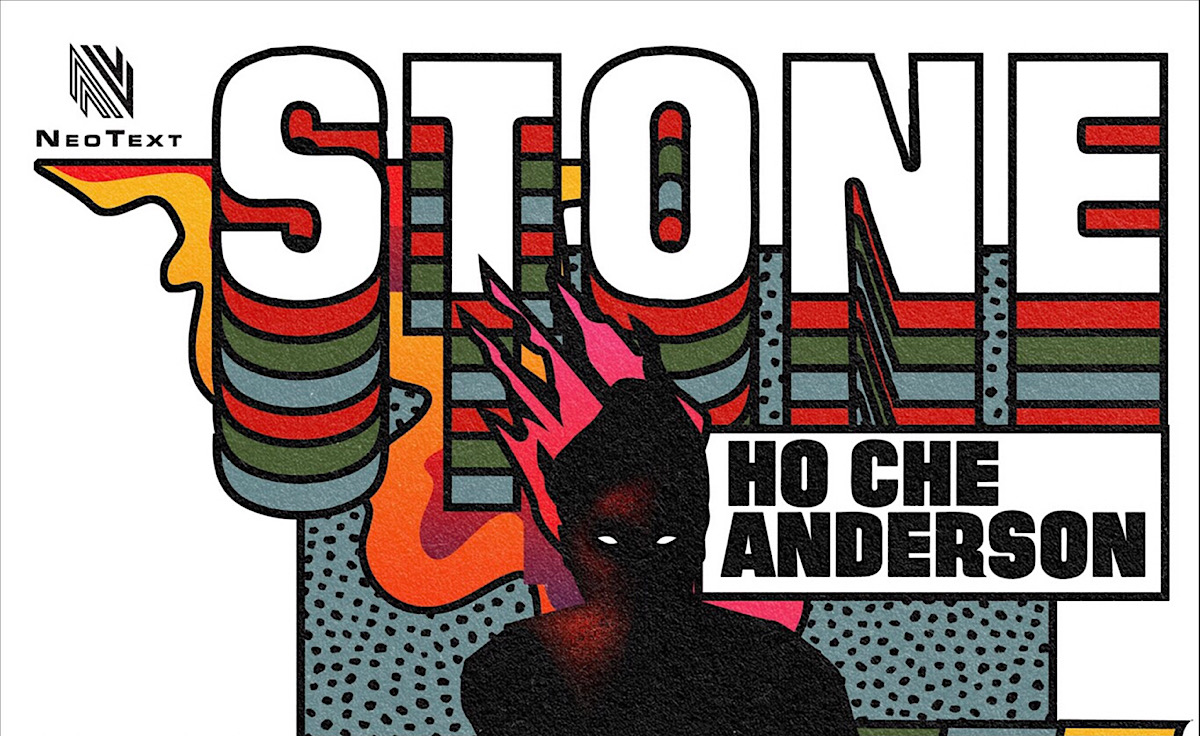

If there’s a book that captures a mood, a moment, or a movement such as Black Lives Matter, Ho Che Anderson’s Stone is it. In this action-packed, neo-noir revenge fantasy novella, Graciela “Stone” O’Leary, a smoking hot, half-black and half-Latina heroine wants to use her basketball skills and smarts to build a better life for herself and her father. The problem is the ruling elite have a status quo to maintain, and Gracie’s aspirations fall nowhere close to this caste hierarchy of preordained roles. Pigeonholed and preyed upon with nothing left to lose, the only way out is through Old Testament eye-for-eye violence.

In Stone, Anderson (Godhead, King) has created a heroine whose struggle and pain embody the darker sentiments of 2020 and whose voice resonates with hope for the inevitable sea of change to come. Anderson talked to The Beat about the divisive politics of meritocracy and his aspirations for Gracie’s future.

Nancy Powell: Are you a political junkie? I ask because “merit and order” echoes the “law and order” language happening today.

Ho Che Anderson: “Political junkie” is a bit strong. I also have a healthy pop culture appetite. I just like to know what’s going on around me, I like to know the players in the game who have the power to affect my life, and since politics is something that every single one of us has to contend with whether we want to or not, I also see it as storytelling fodder we can all relate to. Politics, like sex, are universal.

Phrases like “Law and Order” always read to me like the elite indoctrinating the proletariat into a life in which we’re happy to continue propping up our social and economic masters. Sorry to be blunt, but it’s almost always rich whites who use words like “merit”. They say things like, ‘I got to where I am through hard work and merit, and you can too if you pull up your boot straps,’ ignoring the fact that they had certain economic, sexual, and class-based advantages that made that success achievable, not just their merit. Those people who clean your homes and succumb to your immigration policies also work hard and have merit, but in their case those attributes simply don’t have the same value. It’s coded language designed to keep groups at odds and propagate a mindset that says you’re second class because you haven’t managed to achieve what I was set up from birth to achieve, and you were set up from birth to fail at.

Powell: And why meritocracy over other forms of rule? It makes sense given how corporate interests control the rule of law in the United States.

Anderson: Because on the surface, the concept of merit has the connotation that with enough intestinal fortitude anything can be achieved by anybody, which in the broadest sense I agree with, so long as we can all acknowledge the reality that it isn’t a level playing field out there, and that certain groups have certain advantages. If those in positions of power can convince the people that we all have the same advantages and that the only reason the women and the people of color haven’t achieved what they’ve achieved is because they weren’t worthy, this is a powerful method of dividing and conquering. ‘Those people over there are failing due to their own shortcomings,’ the dogma goes—it has nothing to do with the fact that we’ve designed the system from the ground up to favor us and that we keep moving the goal posts of success when they get too close. It’s because those people are lazy. It’s because they’re hysterical and emotional. It’s because they’re not as worthy.

Powell: It feels like you had a lot of fun building Graciela “Stone” O’Leary up as the kick-ass heroine. Where did the inspiration for her character come from?

Anderson: Gracie was nothing but fun from day one, I love her deeply, even at her darkest and most painful, probably because darkness and pain are where I live, for better or worse. I’m like a comedian, I love a good laugh, but those laughs always seem to come from a deep well of grief and anger. That said, she wasn’t my creation. I received a pitch from the masterminds behind NeoText in the form of a short story; I was given a character and a setting and told to transform those elements into an HCA joint and map the future of the character and her world, which I have to tell you is one of the best assignments I’ve ever had.

As soon as I started working with the material I saw it clearly in its entirety and proceeded accordingly. I think I responded so deeply to her because she’s a character I could have created but hadn’t gotten around to yet. She is born of a love of pulp storytelling, of outlaw characters who take the law into their own hands because the agents of the law don’t give a shit about their human rights or about what is right or wrong, only about serving the whims of their masters, which, sadly, is what I see when I watch the news or just look outside my window. I see the people in power concerned only with remaining in power, growing that power, consolidating that power. I see a paramilitary that tells us it is there to serve and protect but is in fact only willing to perform those functions for the class that put them in that position in the first place. Violence and vigilantism are horrifyingly negative factors in the real world. Given that, isn’t it sad that more and more I feel like we need a kick-ass heroine like Stone in the corridors of power right now?

Powell: For a prose novella, the plot has a very lyrical and cinematic quality to it. I could imagine it as a comic book as well. Did you always envision this project as a novella?

Anderson: The idea behind Stone and the series of novellas to follow was that it be prose storytelling, and I was excited by that notion because it felt to me like we were doing modern pulp storytelling. This stuff is definitely inspired to some extent by rags like Black Mask or Speakeasy Stories or Astounding Tales or whatever, magazines with, to be honest, varying degrees of quality in the storytelling. And there’s some “black experience” fiction in there as well, a kind of literary movement prevalent in the 70s. In my perfect world I’d see folks with curled up dog-eared copies of the book on their way to work.

There was a disposable quality to those magazines, a sort of, ‘get in, thrill the reader, and get out’ nature to them that I responded to when I was doing my ’30s pulp review in my teen years and continue to find inspiring, that reckless go-for-broke energy, and there was some of that quality that I wanted to get into Stone. I think I would have been less excited by the prospect if it had been a comic book series we were working on, it just came from a different storytelling tradition. That having been said, I wasn’t trying to simply ape the writing styles of old, I wanted to write something that came from that lineage but was ultimately its own animal with its own biology.

Powell: Is there a movie or particular director that influenced how you storyboarded Stone?

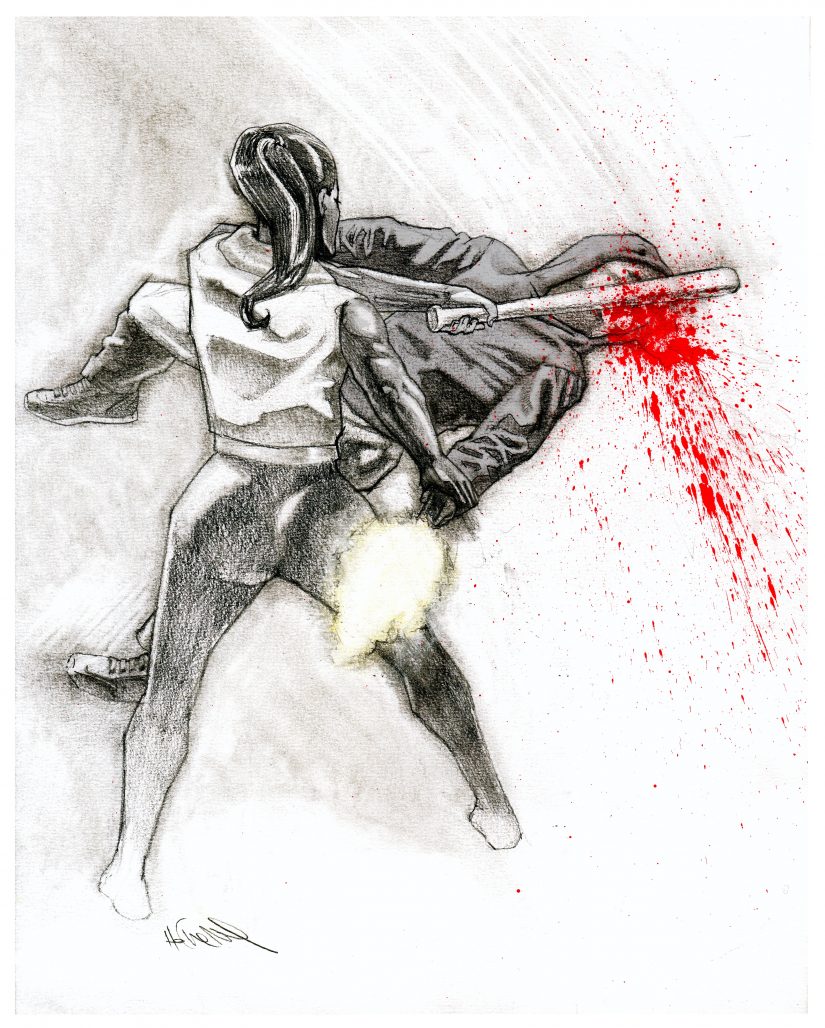

Anderson: Just so we’re on the same page, what I did for Stone was more book illustration than storyboarding, which is a different beast. There weren’t any particular directors that influenced the drawings per se, beyond the base stew of filmmakers I drew on to form the fundamentals of my style many years ago, the Scorseses and Lees and DePalmas and Carpenters of the world. But there were several illustrators I drew inspiration from, like Bob Peak, Robert McGinnis, Bill Sienkiewicz, Ludwig Holdwein, Emory Douglas, Gary Kelley, Richard Amsel, Tom Jung, folks like that.

Powell: Do you prefer writing or drawing?

Anderson: That’s easy, I prefer writing. I was a graphic artist and a designer before I was a writer. A large part of my identity when I was growing up was as an artist, I was known as one of those kids who could draw. It has always come very naturally to me. And to this day I’m extremely grateful that I was able to develop my graphic skills to as high a level as I have, it’s not something I take for granted. But there was a point in my teens when the art and craft of writing became of great interest to me. I discovered that there were things called playwrights and screenwriters and the notion really took hold of me. I started studying the work of Tennessee Williams and August Wilson and David Mamet (sorry, but it was mostly dudes who were the formative influences for better and for worse) and really became deeply enamoured of the craft. I started writing little plays and comic scripts, not even intending to draw them, just because I had a strong desire to produce scripts of one format or another. They were terrible of course but they remain some of the most fun writing I’ve ever done.

As much as I enjoyed and continue to enjoy the practice and impact of creating an image through ink or paint, I’m a storyteller before I’m anything, and the originating idea and the execution of that idea in words really took hold of me. An image is certainly more dazzling on the surface so you’d think the creation of the image would be paramount. But I really like the intellectual sport of conceiving a story and I like the diagrammatical and puzzle-like component of writing a script. As a writer/artist in comics I’m able to blend the two crafts to the point where it’s difficult to tell where one begins and the other ends. But I’m also able to separate them entirely and practice them independent of each other. Unlike most writers I hear talking about their work, I’m not intimidated by the blank page, I enjoy filling that sucker with words and then crafting them into a finished document. That intimidation factor comes with a blank sheet of paper. I sometimes look at that 11×17 board for example and wonder how I got myself into this situation, despite knowing that at some point I’m going to find some fun in the process. Drawing feels just that much more like actual work to me than writing, except for those rare moments when you get into the zone and can make no wrong moves with the image you’re working on. You’ll note I used the word, “rare”.

Powell: And what books have been your favorite to work on throughout your career?

Anderson: That’s a good question. I did a very dark psychological and supernatural horror OGN called Sand & Fury that was a lot of fun despite the sinister nature of the material. I’d made a bunch of money off another project and decided to take some time and scratch this weird itch, which was an incredible creative experience. I’ve also been having fun with my current OGN, the sci-fi action-adventure Godhead, though finding the time to finish up the last batch of pages has been difficult lately. Those boards require a lot of labour but I like the world I created and I dig the highly conceptual and world-building aspects of the material, so once I fall into those pages it’s quite a comforting place to be.

Powell: King, which is a magnificent piece of graphic literature by the way, took you about a decade to research, write and draw. How long did it take for you to conceive and write Stone?

Anderson: Thanks so much for those words about King, I appreciate them. Yeah, that thing was a beast, one I was often unsure I’d be able to successfully wrestle onto the page. I didn’t do the initial conceptual work on Stone so I couldn’t really speak to that, but I did do the writing and the mapping out of where she’s going. I came up with the game plan for where we go from here fairly quickly, the road map was there in my mind within a few days of concentrated thinking and I quickly wrote up my thoughts and plans and let my collaborators know what I wanted to do and was relieved when my ideas went over.

The writing of the book also went fairly quick. I went on vacation in Jamaica for two weeks and by the time I came home I had a finished draft. I let a lot of what was happening on the streets in Mandeville creep into the story. I tend to write quickly; I think about a project for a long time and I write a lot of notes, and when it’s time to do the formal writing I throw a lot of words on the page as fast as I can. Then I spend a lot of time cutting and rewriting. I’m lucky in that words tend to come fairly easily. It helps to enjoy what you do.

Powell: So the book ends on somewhat of an upbeat note, which I suspect will be continued in a sequel. If the political climate were to change and He Who Shall Not Be Named no longer occupies the “throne,” does the central premise on which the story is based change?

Anderson: This is a series of books, we’re building out a whole world with this property, so, yes, there will definitely be sequels if I have anything to say about it. The follow-up, Rizzo, is already in the can, and after that I have a thousand stories I want to tell with Stone O’Leary. If the world catches a break in the next US election and the evil hair piece currently invading the oval office is replaced I’m sure some readjusting will be required—and that would be a good thing. But the threat of the abuse of power is an eternal danger, one we must be constantly vigilant against, so the foundations of our story will always have real world relevance in one way or another. The central premise won’t change just because of the presence of a new POTUS, an actual POTUS. At its core this is a cautionary tale as much as it’s a badass revenge fantasy.

Powell: Finally, if Graciela could be immortalized on the big screen, who would you want to play her?

Anderson: Wow! There’s a question. Gracie is very proudly a literary creation from a long and rich tradition, part folk hero, part force of nature, part golem if you cross her or catch her in a shitty mood, and if that’s what she remains that will be enough. But—in my heart I feel she’s too big to exist solely on the page, she has to be immortalized on screen, it’s her destiny.

Who would I want to play her? By definition she’s a young character, the actress would have to be of college age and would need fierce intelligence and the quality of a warrior. And let’s be honest, looks wouldn’t hurt. Rosario Dawson or Jada Pinkett or Lisa Bonet would have been perfect if this was still the ’90s. Today I could see Zoë Kravitz or Tika Sumpter or maybe Danai Gurira. I’m also really partial to Naomi Ackie and Jurnee Smollett. I’m of course forgetting a ton of great talent that soon I’ll be kicking myself for not remembering. My real desire though would be to discover a great new performer and have this become her first great role. I guess we’ll just have to see how things play out.