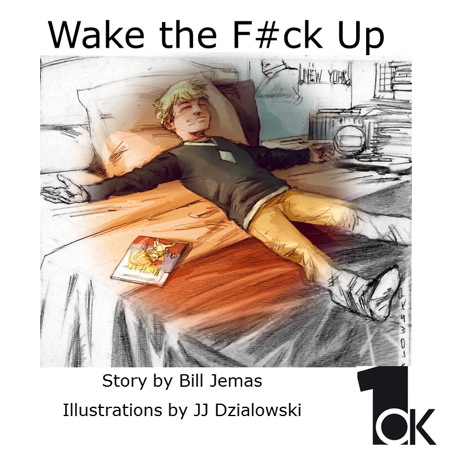

[You can’t run a comics company without making some waves, and the name Bill Jemas still conjures up strong reactions from many who were around when he ran Marvel from 2000-2004. Jemas, along with Joe Quesada, oversaw a period of revolution and rebirth for Marvel as they started the Ultimates line and made many other business changes. Controversial at the time, Ultimization and other bold moves definitely put Marvel back in the game and provided a blueprint for future company-wide changes—as well as making Brian Michael Bendis, Mark Millar and J. Michael Straczynski household names in households where comics are read.Since leaving Marvel, Jemas has run his own licensing company, 360eps, and engaged in some rather unusual projects, such as a translation of the Bible from Hebrew. He’s also on the board of Alloy Marketing, which specializes in reaching teenaged girls. While Jemas has been dabbling at the edges of comics, he’s coming back in a bigger way with two new projects: Wake The F#ck Up, a comic for tgeens and their exasperated parents Zenescope, and The Transverse Universe, a new superhero universe with an environmental/hopeful message for the future. With his wide knowled of publishing and licensing, we’re always interested in hearing what Jemas thinks of today’s comics market…and where it might be going.]

THE BEAT: What is the origin of Wake the F#ck Up? It’s a bit of a surprising project for you…

JEMAS: I really love Go the F#ck to Sleep. Like half the US population, I saw the Samuel L. Jackson videa and thought it was good and got hold of the book at the bookstore, although more people bought it through Amazon. It was an Amazon bestseller before it ever hit the bookstore. But as a parent of teens, the issue is just the opposite. It isn’t go to bed or go to sleep, it’s get off the couch and get the door. I think parents really wish for their kids to do it, but it’s not so easy anymore. The book is not so much personal experience with my kids, who like to be active and like to get out. But it’s an obsession with the teen world and teen market in general. Do you want your kid to get a job? Teen employment is the highest since WWII. There just aren’t really any jobs for teens. And as the economic situation gets worse and worse, employers are hiring older laborers. We all know if you don’t get a job early you don’t do as well later on. And teen outdoor time is, some surveys say, 10 or 15 minutes a day and we all know it’s very unhealthy and it’s a bad lifestyle. We haven’t given kids the same opportunities to get up and get out and get a job. So part of the book is the parents ranting—which you can read online. The other part, which is in the print part, is the kids’ take on it, and the relatively crappy world our generation is leaving for them.

THE BEAT: You did the video for Wake the F#ck Up. Did you develop the music for it also?

JEMAS: There’s a kid who works for me who only likes to be called Killgore. I asked him to look at the Samuel L. Jackson video and just do a digital storyboard. We were thinking we’d find somebody semi-famous to do the voiceover. He disappeared for two weeks and came back with the rap. I thought it was wonderful. He worked with a friend on the music. I think he’s a very good rapper, and I think it’s actually better than the book. There’s no better feeling as someone who lives in and around the creative community that some thought that you had, and some idea and funding and networking, you think you know what you’re doing and someone like Brian Bendis comes back with a beautiful script, or Mark Millar comes back with a spectacular universe, there’s no better feeling it’s so much better than relying on your own fingers.

THE BEAT: Why did you decide to go with Zenescope? It’s not an obvious choice.

JEMAS: Actually, it started with me talking to a traditional book publisher, talking about a traditional gift book. But I like comics, the book works pretty well as a comic with a comic trim, and they go into comic shops. Most bookstores, the ones that are left, have a place to put a comic book and if they don’t we’ll fork a little money over for display. I thought a comic book, on balance, would be better than a story book. I’ve been a fan of Zenescope from the start, both in terms of their approach to artwork and their writing style. I like what they’ve done, especially with things like Shark Week and on a custom basis. They did that really well. And I like Joe [Brusha, Zenescope president] personally so I called him up and said I could do a comic book or storybook and asked if he would be interested in working with me. I drove down to Pennsylvania and we shook hands. A lot of their work is T&A and I’m not necessarily a T&A guy, but a lot is very well written, and I admire that part of it.

THE BEAT: You mentioned the Shark Week stuff and that was an impressive deal for them. I think the last time I saw you, you were talking about getting back into comics, or dabbling. You toyed with the idea, for a while. What have you seen, what are the pros and cons of getting back in?

JEMAS: There are plenty of pros. There’s an exploding online readership, and this particular comic, Wake the F#ck Up, will be available for free through a digital player. I spent a little bit of money and some time with a bright developer in the UK who’s developed an open source plug-in for WordPress, and to give the guy credit, it’s as good or better as any other comic book player that you can get for free or pay in the marketplace. So I think the readership is strong. New technology, both mobile technology and PC technology, will make them easy to read. To get audience online is easier than ever. And the community is really good at judging what’s good and bad and the feedback is immediate—sometimes it’s rough—but it’s immediate and available. I like that part. I’ve always liked that. I like comic books that are good and succeed and comics that fail that you can learn from.

We had a creative explosion back in the day at Marvel, and a lot of that was because we let creators create, and we let them fail, and just kept at it until the stuff became really really good. I don’t know if I’ve talked about it very much, but the early Ultimates comics, we had dozens and dozens of horrible script, bad artwork. Lots and lots of fails until Brian [Michael Bendis] and Mark [Millar] came along and did scripts, and the Kuberts [Adam and Andy] and Mark Bagley did some beautiful art for us.

So I like that chunk of comics. You can be more creative for less money and less time with better feedback with comics than in any medium I’ve ever been around.

The downside is, it’s awfully hard to make a living. [The Beat laughs.] The state of the beast on the print side…I’ve heard good things about a little resurgence in the past six months that people attribute to DC’s wonderful relaunch. But not withstanding, it’s hard to make a living. The shops are going out of business and can’t afford to order as many comics as they should. I’d like to be part of the group of people who help figure out how to keep the print industry healthy and sustained.

THE BEAT: Ultimization was 11 years ago and there have been many iterations of events and relaunches since then. Do you follow the industry?

JEMAS: I visit comic stores once or twice a month talk, to the owner and find out what’s going on with their particular business, but not an exhaustive study of what’s going on. You just sort of look around and see more and more stores closing and not enough opening to make up for it.

THE BEAT: To ask a more specific question, when you and Joe Quesada were doing the Ultimate line, what was the situation that was facing the industry at that point that made you think you had to take fairly drastic action?

JEMAS: At the time I had just taken the job and sort of shoehorned myself in, they brought me in to be a licensing guy, and I kind of forced myself into the digital side and the publishing side. I spent the first month walking from office to office, retailer to retailer, licensee to licensee and the consensus was we didn’t have teen fans. Teens weren’t reading our comics, they weren’t buying our products. Teens didn’t know or care about superheroes and collectively we felt without the teen market we were doomed.

So Ultimates was intended to be the content at the hub of the wheel and the spokes would be every aspect inside and outside the business. Every department was going to do Ultimates, all the licensees were going to do the Ultimates, and ironically, the movie and TV guys came along last, but when they came along they came along with a vengeance. The idea was to pull ourselves up by our bootstraps by focusing on the teen market.

THE BEAT: Well, it definitely rewrote the rules at the time. You have such wide portfolio of things that you have worked so I am fascinated by your observations on all the aspects of business. Do you still run 360ep, your licensing company?

JEMAS: We ran it for 8 years which is a good run for a small business and then after that point, we were making less money and having less fun. It was too hard for a small player to survive in licensing. Not to complain, because the world changes and you have to change with it, but when there were a lot of regional retail chains, small properties could get a foothold in a region and expand nationally. Small licensing agencies could make a living helping that small property get a foothold. As retail became more and more concentrated, retailers can’t fool around with little, they need the next big, or more accurately, they need what’s big already. There isn’t much of a place for a small licensing agency. You’re either the biggest and the best or you have to step aside. I didn’t have the fire in my belly for more t-shirts or video games. I was happy to see it go, I think I helped everybody who was with me get a decent job and I took a more fun spot on the board of a more fun company called Alloy Media. And that’s where I am now.

THE BEAT: You’re absolutely right in that everything has gotten very big, but it seems there are many opportunities in digital now. Do you think digital is where newer and fresher ideas are coming from?

JEMAS: Yes—but. There’s just not enough money in digital for creators to make a living. So it’s difficult right now. There’s no solid financial model that’s going to apply to a big enough creative base. So for the most, people who subsidized by parents and family and friends. The transition needs to happen and ought to happen, but I don’t see any clear path for it to happen. For comic books, theoretically, I’m starting to launch a new universe, the stuff is in play. The idea is to drive audience through digital distribution and then to start to generate revenues through comic publishing and niche publishing and then hold our breath until we get a TV or movie deal. And that’s okay but on an unsubsidized basis that would be awfully hard to do. I can’t imagine a couple of independent creators trying to pay for their food and rent operating that way.

THE BEAT: And yet people are trying it. Kickstarter has become a new paradigm. A webcomic just yesterday just raised $700,000. [Edit: it’s now up to $1.2 million.]

JEMAS: What was that?

THE BEAT: It’s something called Homestuck and people our age don’t get it but the kids love it. [Brief discussion trying to explain Homestuck from scratch.]

JEMAS: There’s a half a dozen of these things out there show some light at the end of the tunnel. But what’s interesting is a lot of it is preselling and the kind of merchandize that comic stores should be selling. Hopefully this will have an overall good effect on the industry.

THE BEAT: I guess it’s creating more goods than services. Any other advice for the comics industry? [general laughter]

JEMAS: I thought the Ultimates was a very good blueprint. Lots of free distribution, lots of comic book sampling, very aggressive marketing and using partners. You’ve heard me tell the Ultimates story before, but we asked nicely but firmly that the companies who wanted to be in business with us for Spider-man licensing buy ads in the comic books to help keep the prices low. And we asked them to sample roughly 10 million copies and hand them out to kids and teens. There’s a formula out there that did work and ought to work now. It would nice to see publishers do that.

THE BEAT: What are you looking forward to? You are putting out this book, are you going to be doing publishing?

JEMAS: I’m working on a universe now. It’s going slowly but surely. I like the way the content is coming out. It’s not ready for prime time, but it’s ready to show other creators who might be interested in participating. The idea of the universe is to present visions of a brighter future, which is surprisingly unique in our creative community. A fist fight is exciting, a gunfight is more exiting, and firing rockets at people is even more exciting. But that sort of ignores the deep down human need for hope. The niche for the Transverse Universe is a non apocalyptic universe. The work is in development. Over time, you realize your limitations the older you get. I’m not trying to write dialog or do a complete comic book, just work with artists on individual images, and show them through digital storyboard player and hope to find a real round of real writers who are interested in writing narrative stories set in the universe.

THE BEAT: What’s the motivation for the Transverse Universe for you?

JEMAS: It started with a sense of responsibility—not to get too dramatic, but we really haven’t much in the way of opportunities for the next generation of workers. We haven’t created much by way of an environmental prospects for the next generation of kids. I sort of have always been interested in environmental science. I started reading as much as I could by people who had a vision for an environmentally sustainable future. One of the best books is called Plan B by Lester R. Brown. I read that books and dozen others like it, and I thought that comic book artists, especially, could feel the freedom to draw wonderful visions of the future. So I started to script out stories, I wouldn’t call them utopian, but brighter visions of the future.

It started with that, but the more we worked on it, the more fun stories became, the more the characters came to life, and I think with a little bit of luck and hard work and some investment funding, we’ll get to the point where the stories are publishable, and the guys who are working on them can start to make a living.

By the end of the year there’ll be plenty of Transverse. The site is an invitation for writers and artists who are working on this kind of content with me to work out deals together.

[Wake The F#ck Up comes out October 24th.]

The opening line of the article is “You can’t run a comics company without making some waves”

I don’t recall dennis kitchen, chris oliveros, alvin beauniventura, or chris staros (among others) ever “making some waves”.

At least not in the way Jemas did.

Jacob — at least two of the people you name have definitely made waves. I’ll leave those in the know to figure it out.

When Jemas was at Marvel there was an explosion of great new writers, great new (and unique) artists, and most of all, NEW IDEAS. When Jemas left we got House of M and from there it was a pretty quick shift back to formulaic super-hero storytelling, house style art, and the new ideas became few and far between.

Coincidence?

@Johnny, I am going to agree with you for a good part if your statement.

But his ego got the best of him. Hell, just asked Mark Waid.

OOPS!! I ment OF**your statement

;)

Dennis Kitchen didn’t make waves?

That’s definitely a new one…

I meant Denis. D’oh!

Ah! I spelled his name wrong.

(and probably shouldn’t have included him)

I find his objective to be overly ambitious. The problem of full employment is a very serious problem for which there are no real remedies. Even if everyone had the “right” education, it would not translate into full employment or employment at a living wage.

I’m going to quote someone who posted a reply in the discussion area of an article on the Economist website.

rdsg writes “I have run a small business for 30 years. I went from a high of 50 employees to our present 16. Those jobs were replaced by Automation and off shore. It is a Dental Laboratory and these are technical manufacturing jobs.

I do not see how, with or without education, we will replace all of these jobs. We just don’t need the head count. We were able to move from Agro to manufacturing because of the industrial revolution. There is no new endeaver that will replace all of those positions. We can no longer support this population. It is a disturbing reality. We can talk all we want about training and education but please enlighten me on what we should train for considering the size of the unemployed work force and the continuing advances in technology. I am already seeing work in my industry that was outsourced to China coming back because cad cam systems are replacing foreign labor. It’s a small percentage now but bound to increase. That may create one new job to replace the ten lost.

The future as I see it is a smaller population. How we get to that is a question that has many frightening possibilities.”

This point of view suggests is probably the most pessimistic or realistic, depending one someone’s belief system.

Next, is the traditional conservative critique of youth unemployment; “The major issue with America is that kids are encouraged to study what they want, not to learn job skills there is a real demand for that they can pay the bills with. Liberals arts degrees are mostly worthless investments. There are 10 people with poli-sci or psychology degrees for every 1 in math or science fields, but for the same 10 people in lib. arts there are at most 3 jobs.”

However he fails to state how many jobs are for every computer scientist and what “qualifies” mean. Getting a B.S. in Computer Science doesn’t qualify someone to work in areas with high security, especially if that job is not an entry-level job, meaning it is only open to experienced professionals.

The conservative critque of unemployment is expanded upon and it blames higher living standards

and high wages for unemployment.

chubasco says”. We just need to repeal a few laws around here, and put people’s expectations back in line with those they are competing against in the BRIC’s. ”

The reality in BRICS, most people live on a dollar a day, live in shantytowns, live in homes where eight to ten people live in very crowded living units. S

With all these points of view, it’s difficult to know who is correct.

If Bill Jemas has a genuine point to make , that no one else had addressed, or has actually reached a conclusion that is hopeful, he has his work cut out for him.

Comments are closed.