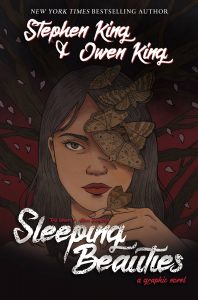

In the novel Sleeping Beauties by Stephen King and Owen King, a small Appalachian town is thrown into chaos when the women who inhabit it begin to become cocooned in mysterious gauze as they sleep… and waking them becomes a deadly proposition. Now, the novel has been adapted to the comics page by Rio Youers, Alison Sampson, Triona Farrell, Christa Miesner, and Valerie Lopez, with the first collected volume (which includes issues 1 through 5) to be published by IDW Publishing on Tuesday, April 20th, 2021.

The Beat caught up with Youers and Sampson over email to find out more about the process of adapting the 700-page novel, what challenges the COVID-19 pandemic created in the making of the comic, and why it was essential to include trans people in the narrative.

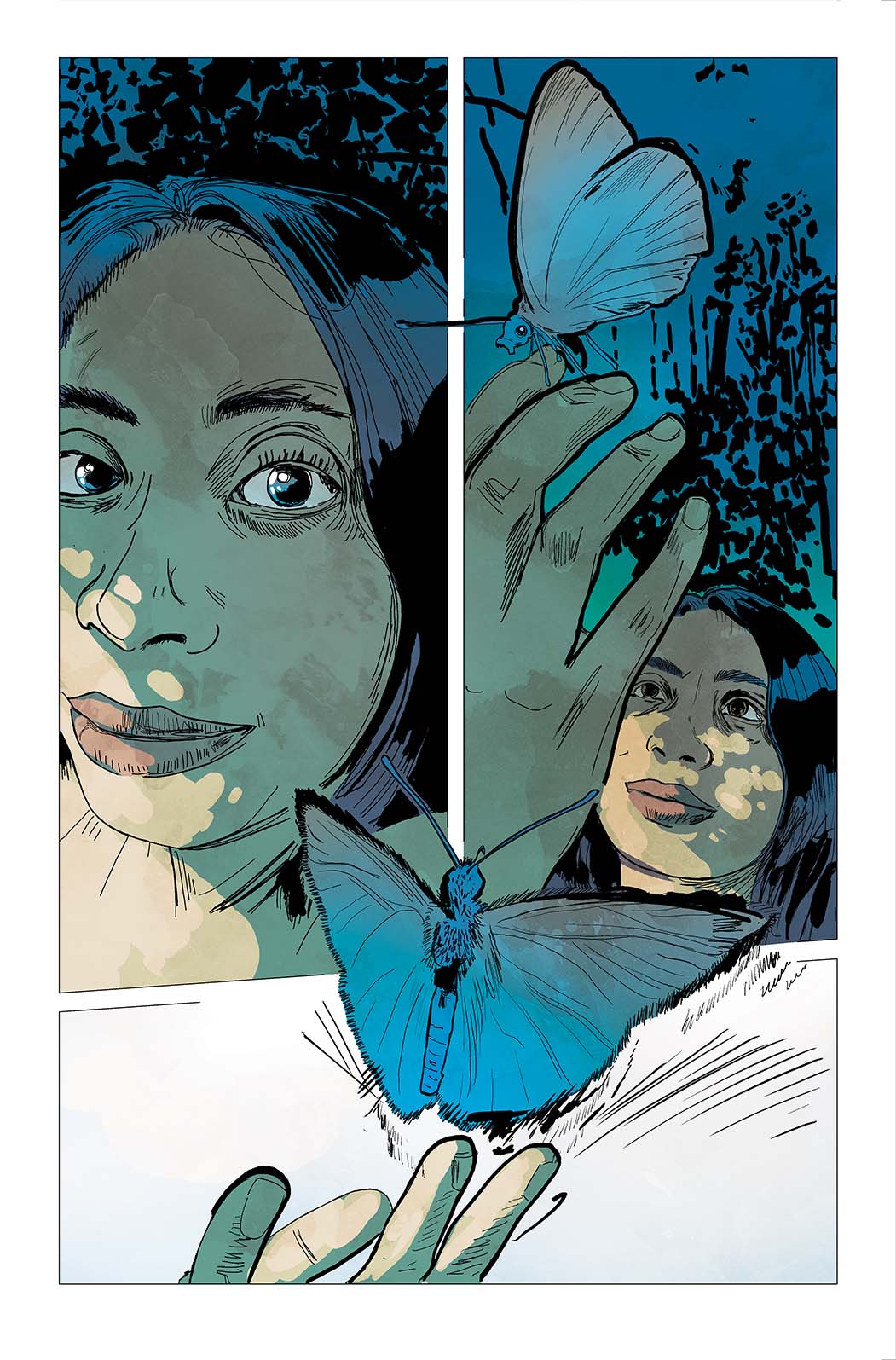

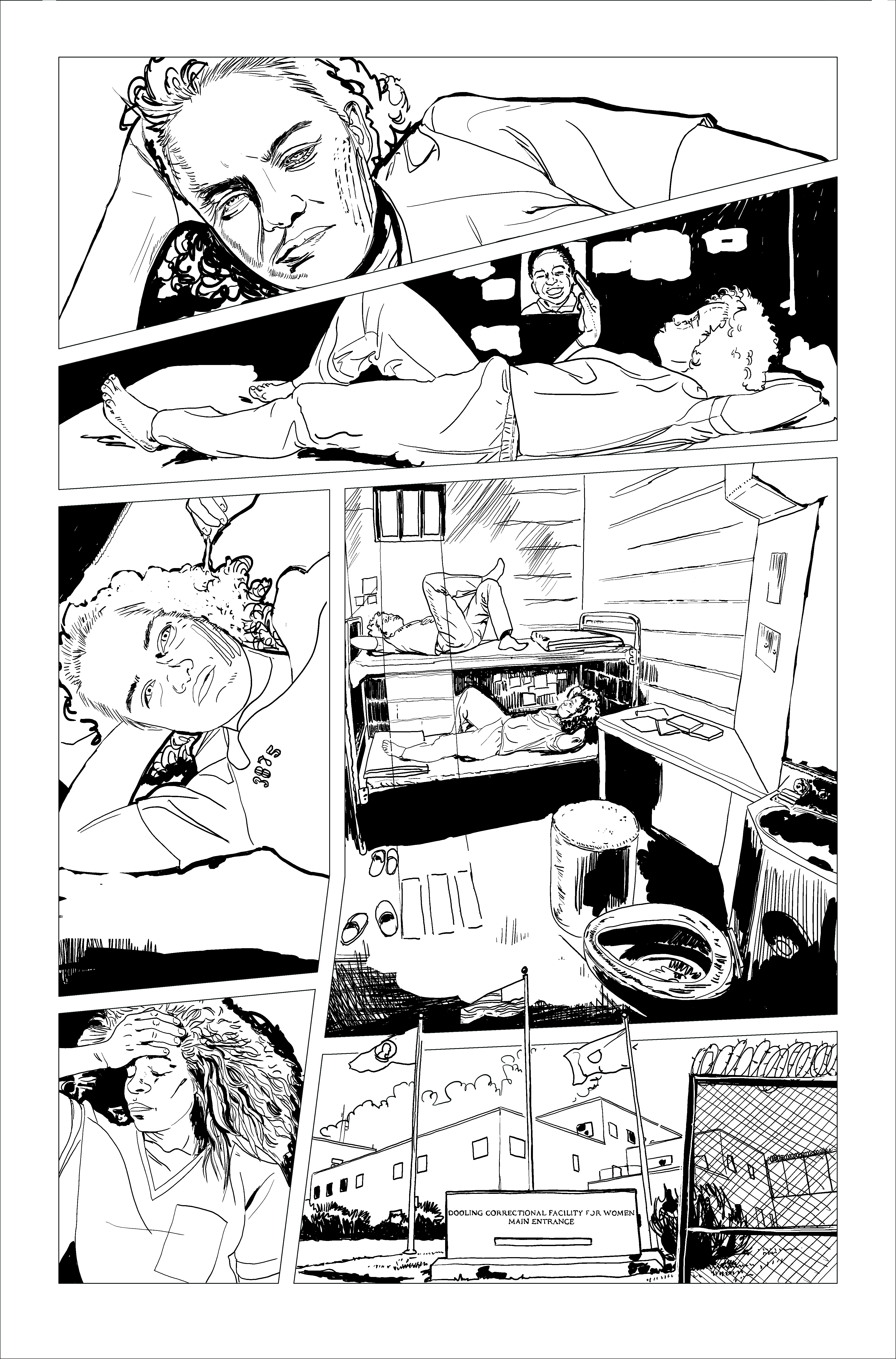

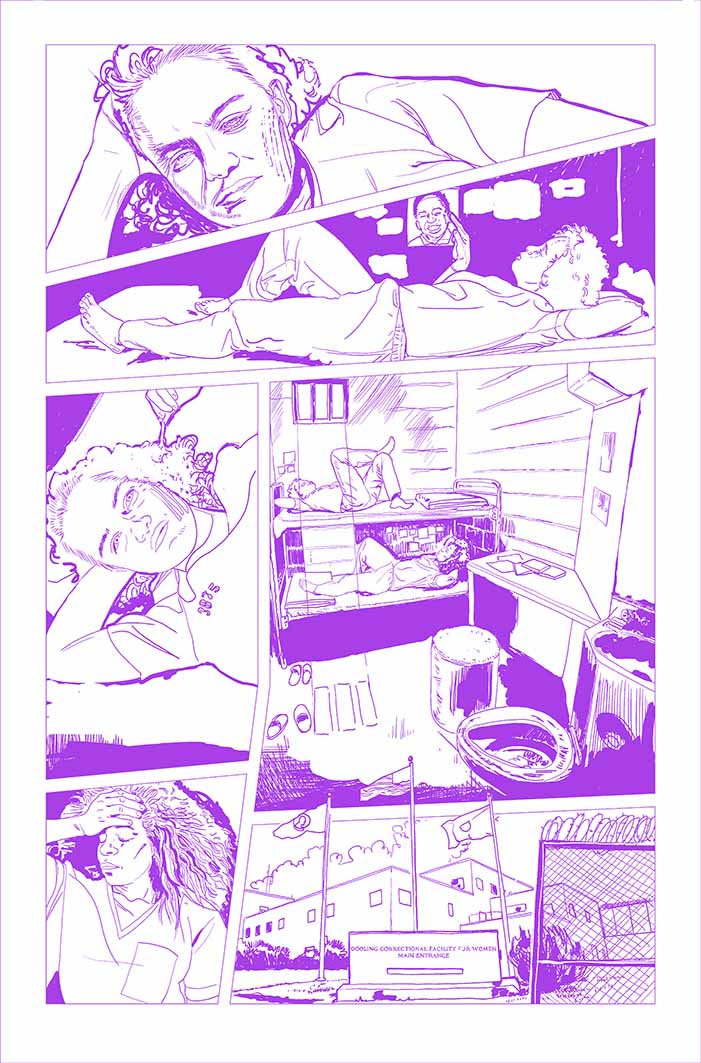

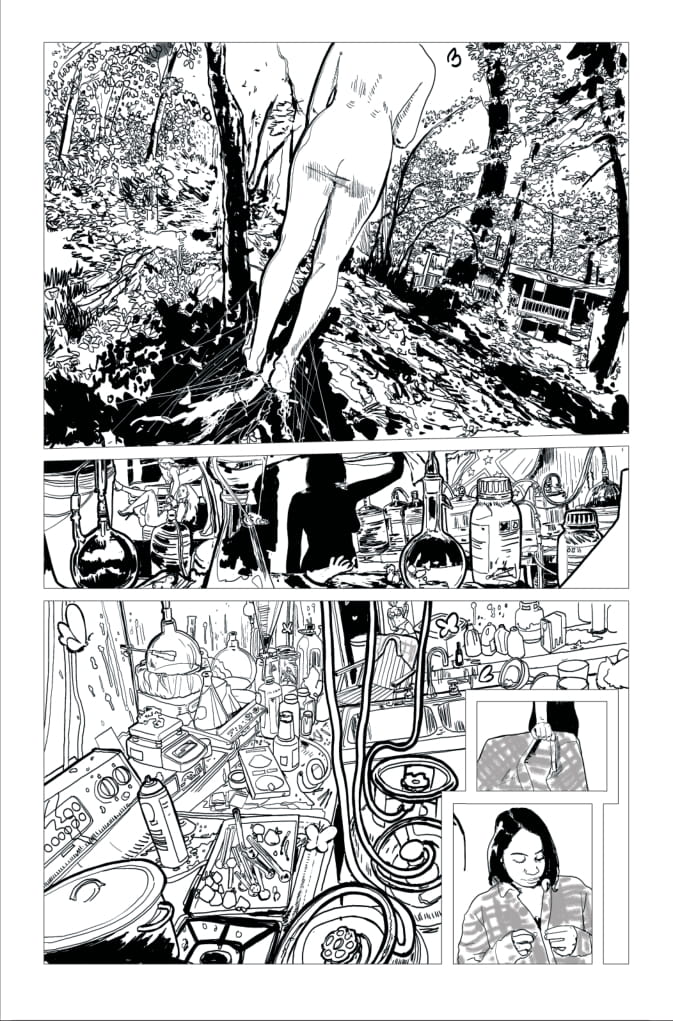

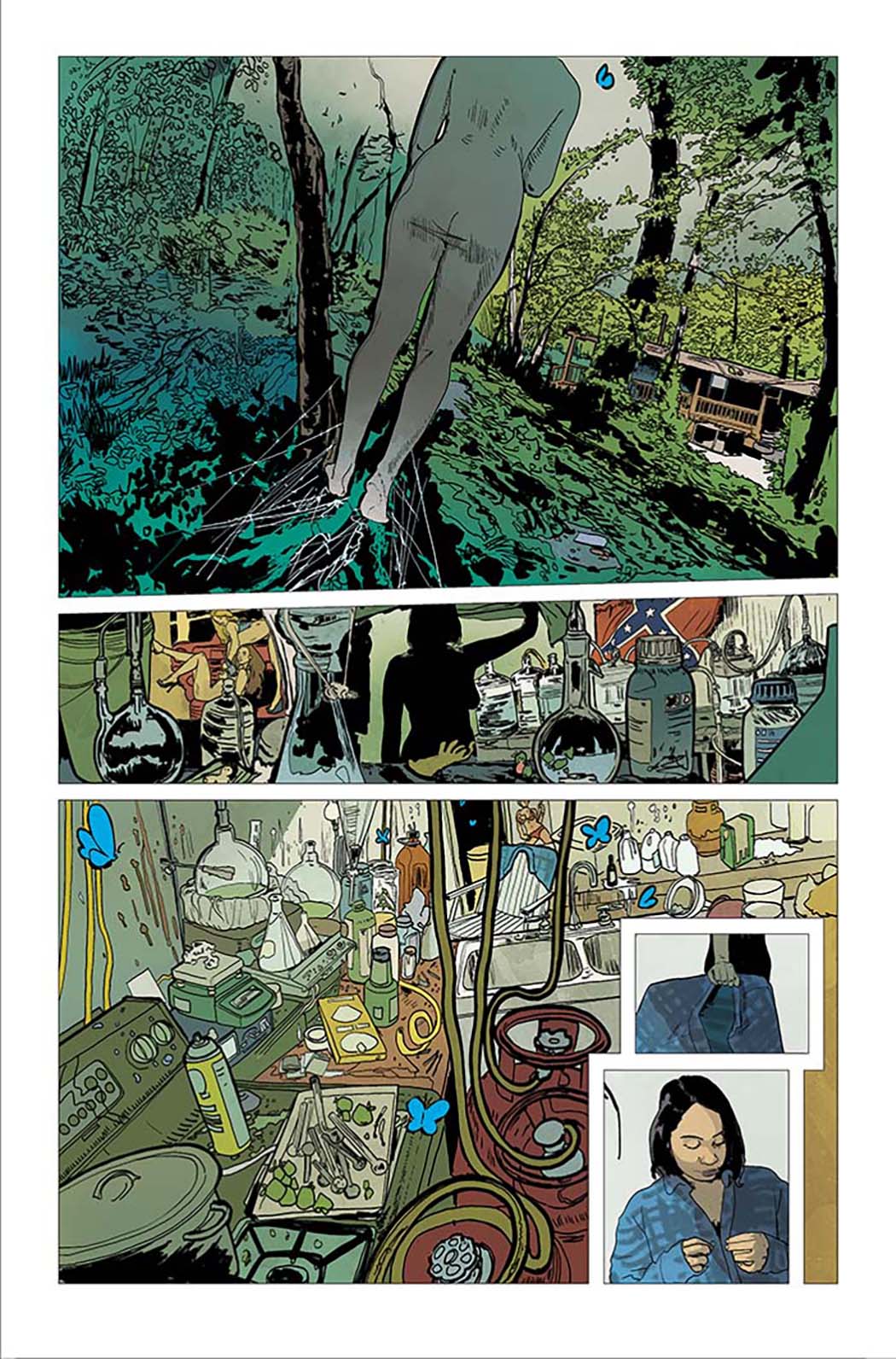

PLUS, The Beat is pleased to present an exclusive glimpse at the creative process behind this adaptation of Sleeping Beauties. First, check out this script of four pages from the Sleeping Beauties graphic novel adaptation. Then, see how the pages are drawn and colored over the course of the interview!

AVERY KAPLAN: When the novel Sleeping Beauties by Stephen King and Owen King was first published in 2017, the story of a global pandemic played differently than it does today. Did the COVID-19 pandemic affect your perspective on the story?

RIO YOUERS: I think I’d handed in seven or eight issues before COVID swept the world, so I’d already written a majority of the material that dealt with the pandemic. So no, it didn’t really affect my perspective in regard to the writing, but I remember reading through those early issues once we had art and letters, and thinking how haunting it all was. Don’t get me wrong, COVID and Aurora are different in so many ways, but there’s certainly some crossover in regard to the confusion, the mixed messaging, the fear, and how it will all resolve.

ALISON SAMPSON: Not really, although it is fair to think it might have. I drew issue 2, which covers the pandemic most closely, actually before the quarantine started, or even before the pandemic was world news. I was completing issue 3 as we went into lockdown and our food supply cut off, and we could not leave the house. So, the pandemic was more a distraction than an influence, as our experience was much different to that of people in the book. We (here in London, UK) had isolation as opposed to a communal uprising (there were Black Lives Matter protests, but I don’t think they are relevant to this), and of course, Covid 19 could come for anybody. What was an influence was the rise of the far right in the USA, for example the Proud Boys, although again, I’d drawn some critical scenes, like the hospital blockade and the riot at the White House before the actual riot at the White House. I underestimated the level of militarisation amongst the public and law enforcement, and the level of rage that there was to be. I drew horses and I should have had tanks, and I had difficulty being able to tell how close people could get to the building, or even what it was like, or how angry they’d be (some of those people screaming in the Michigan’ governors building are really shocking). If I’d been able to be influenced by these events, if they had occurred a few months earlier, Sleeping Beauties would have been pretty hard to look at. It would have been more true to life, but as it turned out, watching America eat itself was far more frightening than anything we could have imagined. Which is truly shocking, really, given what we are talking about. When people ask me about what horror is, I often point to current events, which, to be honest, are often on another level entirely than fiction. We try and reach that level in this book, and as events unfold, my perspective on the story changes, and the events of Sleeping Beauties seem more, not less, real.

KAPLAN: Why is it that a story about gender can so easily take on horrific elements (if you feel this to be the case)?

YOUERS: Once we get beyond the terror of this mysterious pandemic, the rapid disintegration of a world without women is a particularly credible and chilling horror. I think the Kings handled it fantastically well in the novel, and I hope we replicate that in the comic.

SAMPSON: Any story can easily take on horrific elements, easily. It just takes the imagination to do it. I’d say more about this- where the horror does come from, but I feel I’m going slightly into spoilery territory, so I’ll leave that there. What I will say is there is some very extreme material in the book: infanticide, matricide, suicide, murder, rape, mutilation (etcetera) and it could be said to be gendered, but I just don’t think it is. Those crimes could be carried out by anyone, and they sometimes are.

KAPLAN: Was there any particular aspect of adapting Sleeping Beauties from prose to comics that posed a particular challenge, either narratively or visually?

YOUERS: Yeah, absolutely. Not least, the fact that’s it’s a 700-page novel that I had to strip down to a 200-page comic, while maintaining character, theme, story, and visual impact. I made a lot of cuts—I had to. I remember sending my proposed breakdown—issue-by-issue—to Chris Ryall, Stephen King, and Owen King, and being very worried about their reaction. They loved it, though, and have been enthusiastic about every issue. So yeah, I had to leave out some great scenes and characters (some of my personal favorites), but the essence of what makes Sleeping Beauties so great remains.

SAMPSON: Yes, yes there were challenges, both narratively and visually. One might think that an adaptation might be an easier thing to draw, because the story is already known, but we can’t use the story as it was. Our comic is not a 700-page novel, which is largely dialogue, but a highly visual thing. It is a bit like adapting an old building to a new use is both more expensive, difficult and complicated than building a new building- something that surprises a lot of people. This is the same, for some of the same reasons. First up: the story wasn’t written to be a comic, it wasn’t designed to be a comic, so the script is nothing short of a miracle.

Rio and Elizabeth Brei (our editor at IDW) had to work out what to keep and what to leave and how to keep the story intact whilst editing it far farther than it was originally edited as a novel. They effectively had to deconstruct the novel and put it back together again, and then I had to populate it. It is still very dense (we are packing 700 pages of novel into 200 and something pages of graphic novel), the pacing has to be reinvented, since it has been compressed so far. The compression means the panels have to all work very hard, and often I cannot fit the detail in, so it is visible, which leads me to adding panels (the script runs at about five panels a page on average). The horror is conceptualised for a novel (something you don’t actually see the content and have to imagine it) which, as it turns out, means that it is pretty extreme for a comic, There’s drawing that horror (I did not draw the abused animal, I did draw the severed penis). And, after all of that there are changes Stephen and Owen may have wished to make to the original to take on board. This is also Rio’s first comic- his background as a novelist makes the work better in my opinion, but it is still his first comic script, and there is an inevitable learning process there. On the other hand, it IS a fantasy book and it is right up my street to draw and I very much have enjoyed that challenge. Then there’s also people’s expectations, both positive and negative to deal with. They may feel they know this book already, but novels are not for everybody, and the comic opens up access for more people to read and engage the Kings’ work. It has to stand up on its own- but it is not creator owned. so that is also a challenge, to breathe life into someone else’s story.

There’s no page budget as you might have for something written as a comic- every page is maxed out in terms of content. We use quite a lot of devices to fit things in: phones, social media, tv, maps, road signs, fake polaroids, newspapers and so on. Pictures in pictures. There’s still a lot of dialogue and I have to place the lettering in the layouts to ensure a fit (the layout is LOT to do with fitting the dialogue- yet another reason to add panels). There’s an abnormally large number of characters, perhaps 24 different speaking parts on average per book, and that’s not always repeated book to book and doesn’t include crowd scenes- not very page-budget friendly. I do not get to draw (as one interviewer put it) the goblin market, or its comic equivalent, and West Virginia is real. This is a King book- there’s a lot of inescapable reality in those and it is unglamourised, but also not stereotypical. That meant quite a bit pf research to fill out the visuals. Reality also caught up with me- as per my previous answer, but a bit late to use the reference. This said, the characters are fantastic. It is much more of a diverse book that one might imagine, and we have made it more diverse again- a brown Evie (my model for the character is Trinidadian), a gender bent Van, a different West Virginia than the one most people know.

I deliberately didn’t read the novel before I drew the work, so I have been working with the script alone and that helped, to be honest. You can have too much information. If it is a mystery for them it is also a mystery for me- and that helps with the art, a lot. What this also means is that I am in the same shoes as the reader, but also it means I’m taken further from the novel and more towards something that stands on its own, a better, clearer adaptation.

KAPLAN: Was it important to include trans people in the story?

YOUERS: This was one of the earliest conversations between me, the Kings, and the editing team. Aurora is a gender-based virus, and it was important to us to show that the Mother Tree is in harmony with the gender spectrum. There’s a lovely scene between Clint and Evie in Issue #2 to this effect. It’s one of my favorite pages, and Alison’s artwork is stunning.

SAMPSON: Very much so. And they are included, trans men and trans women, as are non-binary and intersex people, and people who couldn’t put words to it, but knew how they feel and where they wanted to be. It is my job as an artist to take the agency I have and use it responsibly and being responsible is telling things how they are. Because trans men are men, and trans women are women, and gender is not a binary thing, but also, much, much more than that. To exclude people from the book is not only odd, but not telling the story we want to tell. Historically, the Sleeping Beauties novel did not include trans people. But my understanding (and Chris Ryall speaks about this on the Sleeping Beauties round table we recorded for the Thought Bubble YouTube channel) is that Stephen and Owen King asked that the comic be inclusive where the novel was not, and be written differently, and Rio Youers took that on board and wrote it into the script, and it is there. My understanding is that IDW consulted with trans writers on the script. So not only do I think it was important, it was requested. Additionally, to this, there’s so much we can do with how we depict people in popular culture, where we can help, something particularly important at this time when legislation is being drawn up to disadvantage trans people. If we get used to seeing people whose gender is fluid, or who are not (say) identifiable to a gender stereotype, or strictly male or female passing and accept them for who they are, it will be easier for those people in life. Pop culture can be a tool in that. It is proper for (say) trans men just to be seen as men, to just fit in, to just be part of the room full of men, or whatever. Who doesn’t want to be seen for what they are? So, I don’t make a thing of this, however people identify themselves. Those people are just there in the place they want to be, because this is what life is. Suffice to say, a number of real trans and non-binary people were involved in the making of the art, and the making of the book on its own allowed a fair bit of self-expression.

KAPLAN: Rio, you’ve written prose novels like Lola on Fire and The Forgotten Girl, but (I believe) adapting Sleeping Beauties is your first foray into comics. How does the process of writing a comic script compare with writing prose?

YOUERS: I’d written a Zombies Vs. Robots twelve-pager for Chris Ryall eight or nine years ago, which isn’t much, but it at least meant that I wasn’t going into Sleeping Beauties completely cold. That’s a good thing, because the process is completely different. At least it was for me.

But there are comparisons, obviously. And it all comes down to the single most important aspect, which is the story. Whether you’re doing it with paragraphs or panels, the objective is to take the reader on a journey, to have them love (or hate) your characters, to run them through the emotional sawmill, and of course to entertain them. Comics and prose may be as different as skateboards and motorcycles, but they’re both vessels for transportation.

KAPLAN: Alison, I am a huge fan of Winnebago Graveyard, which (according to my understanding) was based on your original idea. Does your process differ when working on an adaptation as compared to an original story?

SAMPSON: To clarify, how Winnebago Graveyard came around is that Steve Niles asked me if I wanted to draw Satanists in Texas or Monsters in Space, and I took the Satanists in Texas. I made some art based on Steve’s outline and that was the pitch, then, Steve and I had some conversations about what I was really interested in (ruralophobia and being paranoid in empty landscapes, outsider fear, agricultural horror, James Herbert, 1970s pulp books) and then Steve wrote the script and I drew it. So that had a particular and unique process as a creator owned book, and I have a story credit because that is correct for artists on creator owned comics and in this instance. Sleeping Beauties is not that, and for me was a fairly straightforward piece of work for hire, although as it turns out I’ve probably brought more to the table, because of the nature of the challenge. I’ve done a LOT more design work on Sleeping Beauties, and the look of the comic is very organic to what the comic is (in that form follows function).

In terms of my actual process, Sleeping Beauties has essentially been the same- read script, design layouts, draw pencils, draw inks, send off color-ready art. Plus the answers I mentioned in my answer about the (very substantial) challenges of the adaptation- for example going from perhaps four named characters to upwards of forty. I’ve assisted a bit with the lettering (mainly because I’ve needed to adapt the script a bit to fit the text in), so there’s been a bit of collaboration there with the editing side. Steve and Rio are not the same people and that has made a bit of difference, but then Steve built his script up from ideas and conversations and four pages of art and has literally decades of experience. Rio had the arguably much harder task of having a thick paperback full of dense prose to break down- and then build back up again and this is his first comic, although he has had an editor where WG did not. In short, WG was a very free book, whatever we wanted it to be, Sleeping Beauties is all about the constraints.

KAPLAN: I’m curious if there’s a particular Stephen King story that you consider to be your favorite?

YOUERS: In novels, I’d say The Stand. For me, it’s the perfect book. More an experience than a novel. The characters, the scope, the richness of a landscape beset with good and evil. It’s even more impressive when you consider that King wrote that book, what … forty years ago? Forty-five? Before computers, and long before the internet. He was a young dude at the time, and he hammered that monster out on his typewriter, one page at a time. I just love that.

In short fiction, there’ll always be a place in my heart for “Survivor Type,” and I’ve read “The End of the Whole Mess” a dozen times, I bet. Such a smart and wonderful piece of fiction. Speaking of which … I just read “Rabbit,” by Owen King, which will soon be published in the anthology Minor Characters, edited by Jaime Clarke. Owen’s contribution is dizzyingly good. He’s such a fabulous writer.

SAMPSON: I have several favorites. I like Carrie for its relatability, and sense of nostalgia (classic 1970s grossness! something we reached for with Winnebago Graveyard). I like Salem’s Lot for its paranoia. And I like The Stand because of its epic nature. It may not be the most dramatic of King’s stories, but I’ve listened to it on audiobook several times and it doesn’t fail to take you to where the story is and give you relatable characters and just that touch of fear of the unknown. You can see it. This is something all King’s books do to a greater or lesser extent, and something I tried to do with SB.

KAPLAN: Have there been any comics or books that you have especially enjoyed reading lately?

YOUERS: Well, keeping it in the King family … A Basketful of Heads by Joe Hill. Ghoulish, funny, and brilliant. I loved it.

SAMPSON: Drawing doesn’t give a lot of time for actual book reading (and like many people in these dark times I’ve dipped into a fair bit of fanfiction), but right now I’m listening to Adrian Tchaikovsky‘s Shadows of the Apt series, NK Jemisin‘s Inheritance trilogy, Talia Levin‘s Culture Warlords book. Comic-wise, it is the Department of Truth, Thor (peak Klein), whatever Ram V and Dan Watters are doing and a rediscovery of home-grown comics by people such as Lucy Sullivan, Gustaffo Vargas, John Lees and Zara Slattery. And Witch Hat Atelier is up next. I’ve also got three scripts to read, one of which I’ve solicited from a favourite writer, and it’ll be their first comic, after millions and millions of words of prose. So, you know, busy times, and a whole load of escapism while I nail down hard reality, authentic police cars and about 50,000 characters being lost and found in West Virginia.

The first volume of Sleeping Beauties will be available at your local comic shop or public library beginning on Tuesday, April 20th, 2021.