By Bryan Hill

I met Joseph Illidge in 2002, before I wrote my first comic book. That year was a lot of me listening to his experience as a writer, filmmaker and comic book editor — and a few arguments about which Frank Miller work was the best, who would you rather have a pint with, Moore or Morrison, and the unbearable importance of Batman.

In 2015, I’m now writing several comics, as is Joseph, and diversity is one of the preeminent issues in the business of entertainment. Joseph, through his weekly column “The Mission” for CBR, stands defiant at the forefront of some difficult, but much needed conversations. Our back and forth tweeting around these issues seemed to urge us to do a formal interview. This is what happened.

Neither one of us held much back.

Bryan Hill: Origin stories matter so what’s yours? What drew you to storytelling? Was it an acute experience or a slow developing process? When were you certain you were going to dedicate your life to it?

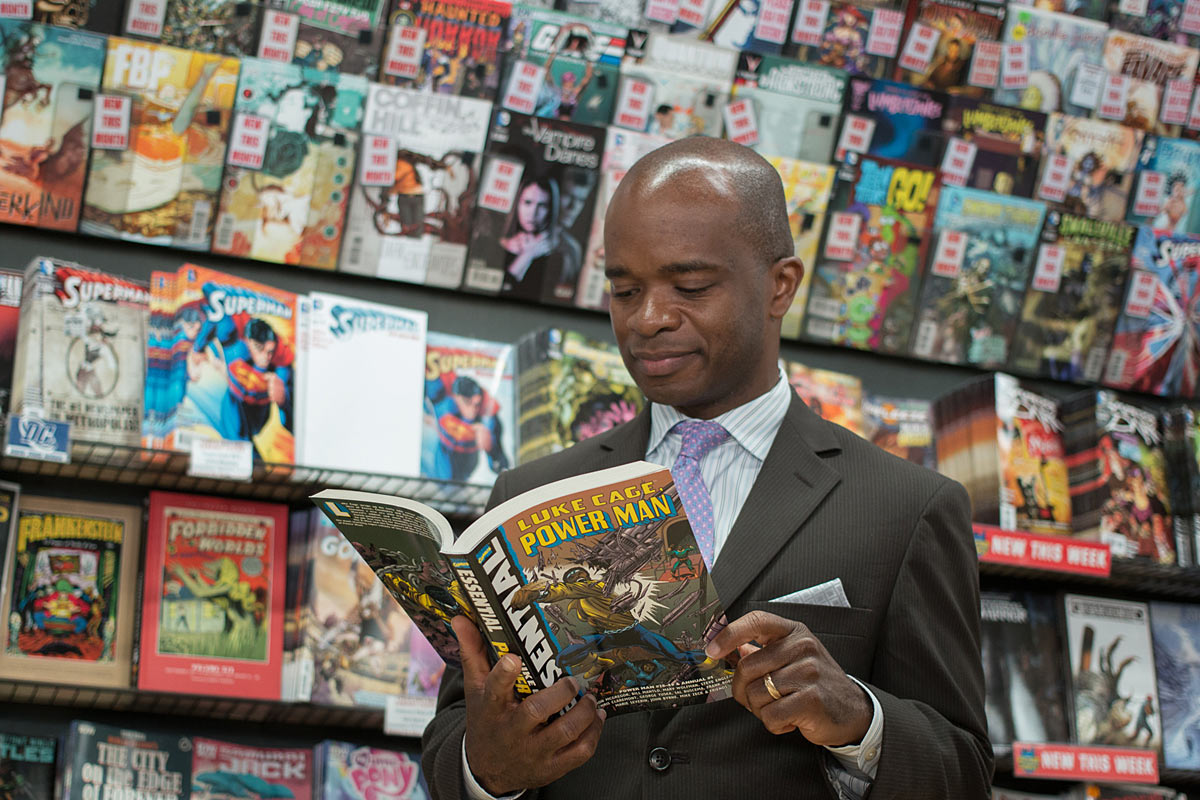

Joseph Illidge: I’ve always been an avid reader, and my mother encouraged it. Between taking me to buy comic books every Friday evening when I was in the second and third grade, to buying me an Encyclopedia Britannica set when I was in the fourth grade, she made sure my young brain was not starving for content.

I was also a nerd way before it was socially acceptable by the mainstream, so fiction, at times, was a more constant companion than peers, especially peers who were cooler than me.

Seeing as how I was more attracted to team books like Uncanny X-Men and Legion of Super-Heroes from the beginning, I think the idea of teamwork and family were themes that attracted me to comic books and stories in general. The idea that great things could be accomplished by enough good people with the same ultimate goal.

The day I started working for Milestone Media, the first Black-owned mainstream comic book company to have a publishing deal with an industry giant like DC Comics, was the day I knew I wanted to tell stories for the rest of my life.

Hill: Someone once told me “Don’t be a black intellectual because they kill those first.” You’re a black man and an intellectual. You survived where many haven’t. How?

Illidge: In addition to having a great support structure of mentors and friends to enrich my life, I realized the importance of diplomacy and communication with precision. You can throw your opinion around like gasoline and light a match, in which case you’re going for a scorched earth effect, or you can wield your thoughts like a crossbow with a set of arrows. Know your message, aim with focus, pull back the arrow, then let it go. Hopefully, your ideas will connect with the audience.

I want to provoke conversations and debates, but in a fair way that maintains mutual respect between parties. I’ve criticized Marvel Comics in various ways, but I’ve known Axel Alonso, Marvel Comics’ Editor-in-chief, for almost twenty years, and he and I are still as cool as ever.

My reputation throughout the industry is solid because people know my intentions are genuine, my message is authentic, and my efforts toward a better comic book industry and medium speak to my love for the artform of comic books and art, in general.

So because people know where I’m coming from, I think that transparency has helped me meet and become friends with like-minded people.

When we support each other in common goals, “killing” the intellectual, Black, female, or otherwise, becomes a harder proposition for the opposition, because that intellectual is not alone.

Hill: You work across disciplines. How has working in different disciplines affected your understanding of them and art in general?

Illidge: Having a background in art from my college years at New York City’s School of Visual Arts helped make me a better editor, because I speak to illustrators in their language and vocabulary of terms.

Being an editor has helped make me a better writer, because the idea that the story is always the first and last thing, the most important thing, gives me a safe distance from my ego. I can be in love with every draft of every script I write, but understanding the editor is my ally and being prepared to jettison ideas helps me get to the better draft in a way that spares me a certain amount of agita.

My writing helps me understand the virtues of various different story forms, so when I write a comic book or graphic novel, I don’t have to strive to imitate cinema because I’m working to exploit the unique aspects of the graphic novel format for telling a story.

Hill: Before I met you, I didn’t know there were editors of color in mainstream comics, or at least that editors of color were working on “white” comics like BATMAN. I was encouraged when I met you. It showed me that we didn’t have to play negro league baseball. We could just play baseball. What’s more important, a person of color initiative like MILESTONE, or people of color getting to play in traditionally “white” sandboxes?

Illidge: The ownership of intellectual properties and creation of companies by people of color is the more important of the two.

Granted, playing in a well-known mainstream sandbox like Marvel Comics or DC Entertainment helps give creators of color notoriety, good pay rates, and an audience, all of which can and should inform and fortify that creator’s individual, self-owned or co-owned, projects.

However, the future will require more creators of color getting together with businesspersons to create formidable companies. It’s the most direct way to become part of the architecture of innovation, product creation, and the potential rewards for profit and empowerment.

Getting to draw or write Superman is not the summit, it’s the illusion of the summit when someone is in a mental desert starving for a form of nourishment the gatekeepers told them was needed to live and thrive.

Intellectual properties owned by corporations should not be the salvation for a creator of color looking to make a long-lasting impact.

Hill: I have to ask this, and it’s gonna piss some people off. Cassandra Cain was more interesting than Barbara Gordon. Damion Scott’s work was amazing. Cassandra Cain makes much more sense as Batgirl than Barbara Gordon. Did DC just “villain” her and then bury her because she’s brown?

My guess is that while Cassandra Cain as Batgirl was making a certain amount of money, she was “tolerated”, but once that changed, they didn’t know what to do with her.

Kill off the Asian girl? That wouldn’t look good.

Making her a villain was the next best option.

Unfortunately, Cassandra Cain was a victim of the mentality that fans don’t want change, and that intellectual properties cannot withstand change.

It’s a shame, because when you look at how DC Entertainment has embraced racebending, and Marvel Comics has really pushed a non-White Ms. Marvel, Cassandra Cain as Batgirl was certainly ahead of the curve by almost fifteen years, and DC Entertainment could have owned that prescience.

At this point, “Batman” writer Scott Snyder has made it clear that major developments are in the works for Cassandra, and writer Gail Simone helped keep the character somewhat visible, but really it feels like a corporate backpedal to me, now.

That said, I look forward to seeing what they do with the great character creators Kelley Puckett and Damion Scott brought to life.

Hill: What was the best experience you had being an editor, and why was it so rewarding?

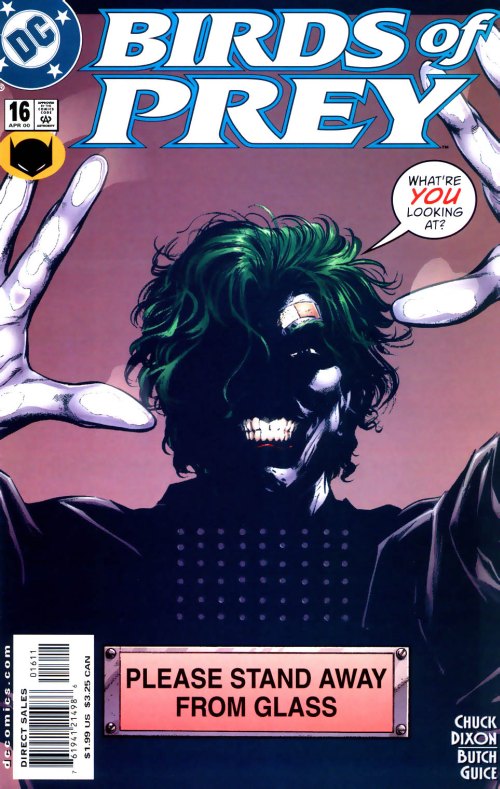

Illidge: While working as a Batman editor for DC Comics, I received a call out of the blue from Dick Giordano. He called to compliment me on Birds of Prey #16, which had Barbara Gordon, The Oracle, face The Joker for the first time in a “Silence of the Lambs” type story by writer Chuck Dixon, illustrator Butch Guice, colorist Gloria Vasquez, and letterer Albert Deguzman. It’s still one of my favorite comics from my editorial career, and Dick was gentlemanly enough to call and tell me he considered it a great comic book.

The man, God rest his soul, was a great guy and is a legend in the business, so that’s about as good as it gets.

Hill: What was your worst experience as an editor (without naming names) and why does it have that distinction?

Illidge: Fortunately, I’ve had very few bad experience in my editorial career thus far.

The worst experience would probably be my last day at Milestone. It was bittersweet, because I wrapped up my last book, but I said goodbye to the first company that gave me a chance, to the men that gave me an opportunity.

I lost faith, and honestly, there was a part of me that felt guilty for working at DC Comics afterwards, due to the complicated relationship between them and Milestone in those days.

The good things I did for creators and comics at DC Comics got me past that guilt, and the returns (plural) of Milestone through the years helped teach me to never lose faith in the power of positive action and impact.

Hill: What is something that creators don’t know about editors that they should?

Illidge: Editors are subject to the trickle-down of corporate manure, and they take more bullets for creators than the public will ever know.

Hill: You explore the role of both race and racism in popular culture. When did you decide you were going to do that exploration and has your perspective changed along that journey?

Illidge: When Jonah Weiland, the Executive Producer of Comic Book Resources, offered me the opportunity to write and manage “The Color Barrier,” my first series of columns for the site, I knew I had an opportunity and responsibility to explore both, without flinching.

My perspective has changed in the sense that I’m more aware of the progress of parallel struggles for diversity in comics, by women, LGBT persons, disabled persons, and so even though the comic book industry has miles to walk, still, to address diversity in a universal manner, I’m more hopeful every day. Setbacks and slights against people in the aforementioned groups do not affect the inertia of my hope in the slightest.

Hill: Why do you think comic book companies are very willing to create and promote characters that suffer prejudice because of their diversity, but they seem to not want diverse creators to tell stories about those characters? Is it just fear and if so, of what?

Illidge: Creating diverse characters is easy, especially when the industry assigns most of their creation to the mostly non-POC writers pool of their companies.

Promoting them is easy because the apparatus for such is already in place, and it makes the publishers look impressively progressive.

It’s apparently more difficult because of a lack of desire to expand beyond the paths of least resistance, expand beyond the more publicized writers. That takes effort, it takes work, and people can always use looming deadlines and heavy workloads as excuses to not investigate outside of familiar territory when it comes to discovering writers of color.

Also, I suspect the publishers are afraid of being seen as caving in to public outcry, because, really, what profitable organization wants to give people the impression that their unfavorable criticisms carry weight?

Additionally, when it comes to Black writers, the general assumption that agenda comes with skill. A Black writer, given an opportunity to write The Punisher won’t automatically turn it into a polemic on violence against young Black people in America.

Interesting that a Black writer has never been given the opportunity to write a monthly X-Men series, considering how the premise of that franchise dovetails with racism.

Hill: I feel the existence of a double-standard in comics, but I can’t define it as more than that. Do you feel that way and if so, what do you think is the nature of that double standard?

Illidge: Black people are respected as consumers, but not as writers, in general, by the major publishers. Full stop.

Hill: What do you believe is the most underserved market in the world of popular culture, comics and beyond?

Illidge: Disabled persons.

Hill: In your CBR column, THE MISSION, you often reach the conclusion that attention to diversity is transient, a strategic reaction to social pressure, but rarely does it persist beyond a news cycle. How can that change?

Illidge: Two ways, at the least.

People from the groups not benefitting from equality can band together in unified efforts. Join up and create companies that create formidable product. Carve out new territories and command some market share. When success is achieved without the aid of popular companies, their attention turns to you. They seek you out.

That’s when the real discussion and negotiations can begin.

In addition, we cannot let up on the gatekeepers. Remain vigilant, give credit where it’s due, and honest examination always. Consistent, intelligent discourse combined with action can chip away at walls of corporate indifference.

When cereal companies make commercials targeted at interracial couples, when DC Comics announced two female-centric lines inside of two months…these things confirm an understanding of our financial power, and our capacity to spend our money on their competitors.

Hill: I know a bit about one of your current projects, a graphic novel about the Harlem Renaissance, but I don’t know much more than that. What is it and what should readers expect?

Illidge: The graphic novel is called The Ren, a 200-plus page story about a romance between Black teenage artists, one from Georgia and the other from Harlem, during the Harlem Renaissance years. In the midst of a crime war, the couple try to make their way, while doing a little growing up at the same time. The story was created by myself and co-writer Shawn Martinbrough, the artist on Image Comics’ “Thief of Thieves” series, along with illustrator Grey Williamson. I consider it a love letter to creative artists of all ages everywhere, who struggle within a world getting more complicated day by day.

The Ren will be published by First Second Books, the house behind critically-acclaimed graphic novels such as This One Summer and American-Born Chinese.

Hill: Many writers I know have rituals for working, music they choose, a place they like to work? What is your creation ritual?

Illidge: Put on some comfortable clothes, eat some food, do something active for ten minutes, sit at the chair, choose a Pandora station, and hit the keyboard. Rinse, repeat.

Keep two Google windows open for research and fact-checking.

Stop when my thoughts take on the consistency of molasses.

Hill: Did you have mentors, and if so, can you name some of them and what you learned (and likely continue to learn) from them?

Illidge: My mentors of past and present are Derek T. Dingle, Dwayne McDuffie, Michael Davis, and Denys Cowan, four of the five founders of Milestone Media, Inc. Dennis O’Neil, former Batman Group Editor, co-creator of Ra’s Al Ghul, and critically-acclaimed writer of many a Batman story, Richard Dragon, Kung-Fu Fighter, The Question, and many other books by DC Comics. Steven Barnes, novelist, martial artist, and lifestyle guru/advisor. I have a new mentor, helping me with my global goals.

In general, what I learn from them is professionalism, patience, control of the message, and balance.

Hill: Do you think that the business synergy between comics and film, while certainly lucrative for both spheres, has negatively affected the quality of comic books? It’s not a loaded question. I honestly am not sure most of the time and I’m curious about what you think.

Illidge: I think the quality of comic books overall has never been better, and there are certainly more opportunities for comic book creators to receive well-deserved visibility and profit due to the synergy between comic books and Hollywood.

Unfortunately, the synergy has led to greater corporate oversight, which has stifled creativity in various instances. It’s no coincidence that more high-profile creators have more creator-owned projects in monthly publication than ever. That’s the result of ennui and the exhaustion of navigating around story for reasons connected with profit.

Hill: Many people reading this are creators looking to become professional with their work. I’m sure you have a multitude of perspectives to share, but if you don’t mind boiling it down into three things all creators should keep in mind during the transition into professional work, what would those three things be?

Illidge: Find allies and advisors who will tell you the truth, in order for you to become better at your craft.

Aspire to create work as good as the works you admire, on schedule.

Develop a mental callouses, because criticism is inevitable and you will have to make many changes on the way to good work.

Hill: Miles or Peter? And why?

Illidge: Peter.

He lost his uncle to a criminal, his first love to a villain, his first wife to a deal with The Devil, faces pain and suffering with humor and hope, and never, ever gives up.

Bryan Hill is a comic author and screenwriter. Currently he is writing POSTAL for Top Cow/Image. He lives and works in Los Angeles.

Great interview.

One of the most impressive and inspiring Q&As with a comics industry professional that I’ve ever read; kudos to both interviewer and subject.

Comments are closed.