Movies with dedicated prosthetics work, costume design, props, fake blood, and manipulable monster masks and suits tend to combine all these elements to produce some of the most iconic creatures and characters ever put on film. Whenever interest peaks as to who were the people responsible for them, though, the result is usually a singular name belonging to a male visual effects creator. They include Rick Baker, Tom Savini, Greg Nicotero, Rob Botin, all legends in their field, without question. Problem is, these designers didn’t work alone. In many cases, a film’s makeup and VFX design as a whole is a collection of ideas that come from a whole team of artists, namely the people that shoulder the brunt of the hands-on work to bring child-eating clowns or ninja turtles to life in the big and the small screen. Many times, they elevate the original concept and should get the big designer credits themselves.

Women effects artists have done career and movie-defining work in these spaces, but no spotlight graces their specific roles and contributions due to antiquated male-centered attitudes towards recognition coupled with the ever-persistent presence of deeply rooted sexism in the industry (which has seen some change but is still very much a hurdle that female creators have to navigate).

This past edition of San Diego Comic Con featured a panel that injected a healthy dose of hope in righting the wrongs female VFX artists have faced in terms of having their work recognized in the film industry. In a panel titled “Forgotten Creators: The Women Behind the Monster,” effects artists R.E. Nelson and costume maker Nikki Blackwell did precisely that.

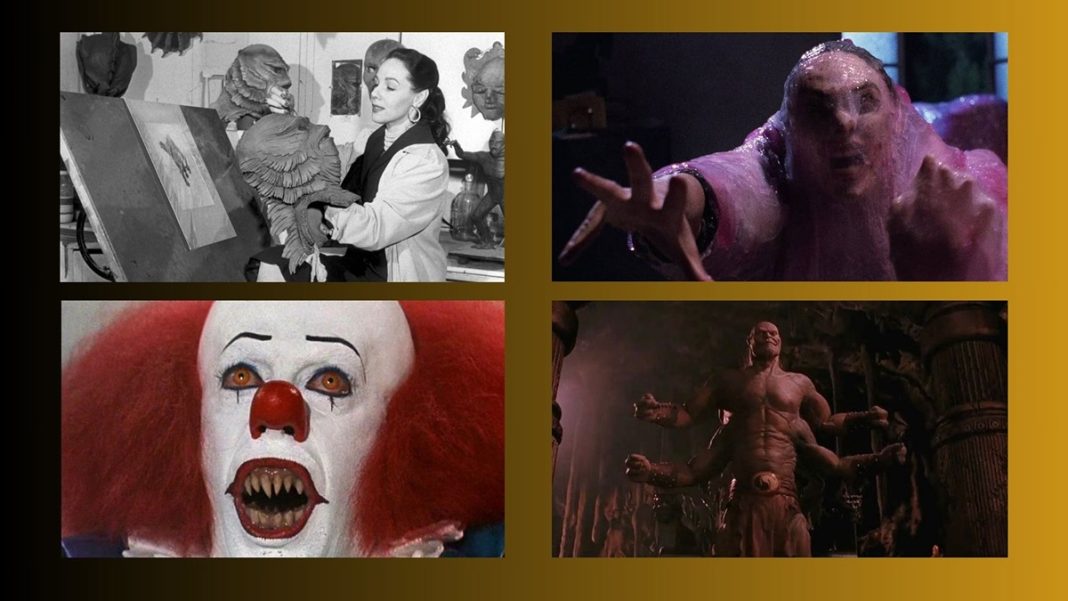

They invited three female visual effects legends whose work helped define horror, science fiction, and fantasy throughout the 1980s and 1990s to talk the inner workings of the industry and the hardships that come with building a career within it as a woman. The panelists featured were Terri Fluker (Drag Me to Hell, The Blob, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas), Tonya Ridenour Nelson (It miniseries, Army of Darkness, Gremlins 2), and Wendy Polutanovich (Mortal Kombat ’95, Star Trek: Picard, Earth Girls are Easy).

The panel was easily one of the best and most important in the convention, all while also functioning as a soft launch for a much larger project called Creative Conversations, in which Nelson and Blackwell hope to rescue more stories from creators that haven’t gotten the attention they deserve. The Beat caught up with Nelson and Blackwell to talk about what recognition looks like and what it takes to get it for women in VFX.

RICARDO SERRANO: What drove you to take on this project for female recognition in visual effects work?

RACHEL NELSON: We want to document stories from forgotten creators, plain and simple. We want an accessible collection of stories and recordings that don’t just live and die on a hard drive somewhere. I developed the idea and brought on Nikki as a consultant. We’re best friends and we’ve worked together for over a decade now.

Right now, we’re trying to find our niche. One of the things that both of us really like is providing additional types of entertainment, especially edutainment. We like making content that’s not really out there, stuff that entertains but also informs. We like thinking outside the box, which is what led us to start paneling at comic conventions. We’ve done WonderCon, and I hope to make my way to New York Comic Con in the near future.

NIKKI BLACKWELL: I actually started as a cosplayer before specializing in costuming and corset design and was mentored by Rachel’s mom (Tonya Ridenour). I went on to be mentored by many other artists and creators as well, which gave me a good sense of how difficult it can be to be a woman in this field. I’m always impressed by the amount of stories that still haven’t been told out there. Getting them down for others to hear and learn from was motivation enough.

NELSON: I just wanted to add real quick that one of the things that makes Nikki so great is that she takes her time and does things correctly. There’s so much attention to detail in her work.

BLACKWELL: Thanks! I think a lot of this is about knowing what’ll make something better for any given project. There’s a time to cut corners and there’s a time not to. Done is better than perfect, for sure. But the industry that I am in has a lot of people who are like “No, it has to be perfect and I will kill my sanity for it.” I’m not like that. There’s a time and a place. Sure, there are certain techniques where near-perfection is key, but mental and emotional health is important too. You have to know when to go hard and when to ease up. Weigh the corners that you can cut versus the corners you can’t cut. Decide what really deserves to be highlighted.

SERRANO: Doing a cursory search on female creature designers online was way more frustrating than it should’ve been given the lack of a complete or accurate list of credits for women FX artists in film. Why is this still a problem today, and what do you think is helping mitigate that?

NELSON: Social media is definitely helping to create a sense of awareness that gives creators both old and new more visibility. I think it’s important to help older generations become literate in social media, to become literate in the things that can be done online.

One of the things that keep recognition a struggle today is that there’s not a lot of people out there documenting what everyone does in a movie, down to the specific roles. We need to make sure there are people who can go and document this.

Another big problem is that the industry is still, in many ways, like an advanced boys’ club. You do have pioneers who pushed through and were able to get recognized, like Ve Neil who is one of the most decorated special effects artists out there. But what’s funny about her case is that whenever I was talking to some of her male contemporaries when I was doing effects work, I remember hearing little bits of chatter from some of them about how everyone is always mentioning her. They would roll their eyes and say “well, everyone knows about Ve Neil,” as if she wasn’t that important. They didn’t want to give her credit. But they would go on to talk about Rick Baker and Stan Winston and how they admired them. You need to include Ve Neil in there.

I think part of the reason why a lot of creators don’t show that same amount of respect to legacy creators like Neil is that they don’t know about their work because it hasn’t been as documented as well as the men’s. Now with the internet, it’s time to make sure our online portfolios are up to date and have our credits well recorded.

BLACKWELL: When I was first getting into the industry, and even now, I noticed there’s so many job positions and so many hands that go into making a piece that sometimes the delineation of jobs or even the job titles are just overwhelming. I often went like, “wait, that exists?”

Some artists just do a very small part of a larger design, which means it can be hard for somebody who is not in that industry to know what a particular job is or that it should be credited. Maybe we need people on set to keep a record of what everyone does, and whether there are multiple people to even give credit to for just one design.

Another thing that I find frustrating as a maker is that a lot of times the designer gets all the credit. Yes, that role is important, but a lot of times, in my experiences, designers can’t make for anything. It’s the makers that have to take this idealistic image and reduce it or bend it and twist it to make it reality. A lot of times, those makers don’t get credit.

SERRANO: It’s a bit like comics in that sense, where the writer and the artist get the spotlight and the inker, letterer, and colorist tend to be seen as secondary players. That’s if they’re recognized at all.

NELSON: Or like with movies where the directors and the actors get all the recognition, maybe the scriptwriter and maybe the cinematographer. Take Lord of the Rings for instance, where Weta FX is used to synthesize an entire group of people that worked to make the special effects and the look of the film come together. We love to synthesize these things too much, and we keep a lot of people in the dark because of it.

BLACKWELL: Exactly. You have to record who’s doing what. Make sure everyone in the team is accounted for in the credits. And we can’t be afraid to be specific. People might reduce us to an incomplete list of artists because the credits themselves don’t specifically say who did what. It’s a list of ten names that might not mean much to anyone. Being thorough in that helps audiences maybe get a better sense of what goes into the job.

SERRANO: Your SDCC ’24 panel, “Forgotten Creators: the women behind the monster” shed some much-needed light on both the good and the bad that women have had to go through to survive in the industry. What has surprised you about some of the stories you’ve heard from other creators?

BLACKWELL: I was pleasantly surprised any time someone talked about physical safety and finance. As somebody who has personally been on a finance journey and is learning how to navigate the industry as an artist while trying to get paid to make a living, it was wonderful to hear Wendy Polutanovich talk about having to learn personal finance and having to take care of her body as she gets older. That was something that I was like, “yes, scream it from the rooftops!” That was so comforting.

There were times I felt like it was crazy I was the person telling everyone to make sure you save money. Knowledge is power and learning those skills are just as important as learning how to do the basics of your job. Unfortunately, money makes the world go round, so hearing somebody say something that I was kind of keeping close to my heart because of how uncomfortable it is really did a lot for me.

That said, I was telling the ladies at dinner after the panel that it is both comforting and very frustrating to hear that, really, not much has changed. The same problems are still around. It’s always about needing more time and more money and more understanding from your higher ups. Only we get the added sexism to it. I’ve been told to my face, “well, your male coworker was able to do the job. Why couldn’t you?” Well, maybe I couldn’t because I was following his directions, or I did not trust my gut and needed guidance. And also, how dare you.”

NELSON: Some things have gotten a bit better, compared to what the women we had on the panel went through, but there are still a lot of problems. I am a victim of multiple sexual assaults, specifically on set. It still happens enough to make you doubt if even a bit of change has happened. Sometimes I think that what has changed is the knowledge that men can’t be blatant anymore with the things they say.

BLACKWELL: It’s subtle, little like passive things that are easy to catch. Stuff that makes you go like “come on, I know what you’re getting at.”

NELSON: There is a lack of understanding and empathy that is still there, especially for anyone with a different background, be it ethnicity, race, gender, or upbringing. Any of those different things can lead certain people to think in the worst kinds of ways.

A lot of times now, men know they can’t say something, but they don’t know why they can’t say it. They don’t want to empathize or understand it. They’ll go, “well, you can’t do that because you could get fired or we could get a sued.”

To go back to the original question, something that surprised me was something you wouldn’t have been able to see during the panel because it happened during the planning process.

I had to recast the some of the panelists, at least three times, for different reasons. Some couldn’t come because the project that they were on got extended. One had a family emergency, and one wasn’t going to be able to make it even with me trying to help with her travel expenses. She simply couldn’t afford to go. But the thing I thought was so amazing was that the minute any one of them had to drop, they immediately started calling a bunch of other people and putting me in contact with them so they could come in and be panelists. It’s not that they didn’t have a desire to do it. It was life circumstances. But they wanted to help out. They wanted me to call other people up to see if they could do it.

They were just excited that someone was going to get seen. This project has gotten a lot of traction. There’s been a lot of good feedback. It’s funny just how many effects people have reached to me and been like, hey, will you do another one, please?

Thank you so much for having us! Thank you for further highlight the struggles of artists and women alike!

Amazing!! This was such a great panel!

Comments are closed.