Vanni: A Family’s Struggle Through the Sri Lankan Conflict

Research and Story by Benjamin Dix

Script and Illustration by Lindsay Pollack

Pennsylvania State University Press/Graphic Medicine

When I think of works of Graphic Medicine, I tend to think about stories of specific medical conditions or memoirs of medical practitioners in certain areas of practice, but Vanni widens my perspective of what the form can offer and it does so in an almost overwhelming way, thanks to the skill that went into its creation.

Vanni begins with a casual exchange that packs an unexpected punch by the end of the book, a nonchalant example of the well-meaning ignorance that so many people endure on a daily basis. It filled me with guilt, actually, considering my own ignorance of the situation in Sri Lanka. The conversation is between a Sri Lankan cabbie and his passengers in London. When the passengers find out where the driver is from, they swoon, remembering their own visit to a resort there for a wedding, and wonder if the cabbie misses Sri Lanka and if he ever goes for a visit. The questions come from the point of view of tourists looking to a perceived sunny beach paradise. Tourism, the new colonialism.

The story then moves back 13 years, to an island in Sri Lanka, Chempiyanpattu, where we see the cabbie, Antoni Ramachandran, then a fisherman, living with his wife Rajini, his mother, and their children. The Sri Lankan government and the Tamil Tigers, a military separatist group seeking an independent homeland for the Hindus in the northeast region of the country, had clashed since the late 1970s, and Antoni’s family was severely affected by the war by the time the book begins. Antoni’s father died in 1982 during riots in the city of Colombo, the capital of Sri Lanka and his brother, Ranjan, joined the Tigers as soon as he came of age.

We also meet other residents of the neighborhood, the Chologars, Nelani and Suji, who have four children, one of whom, Jagajeet, followed Ranjan’s example and also joined the Tigers. Jagajeet drops by for a visit, enlivening the spirits of his family, and bringing the two families together for a gathering in the night. Later, as Antoni fishes under the moonlight, he basks in a rare peaceful moment that will soon become more scarce.

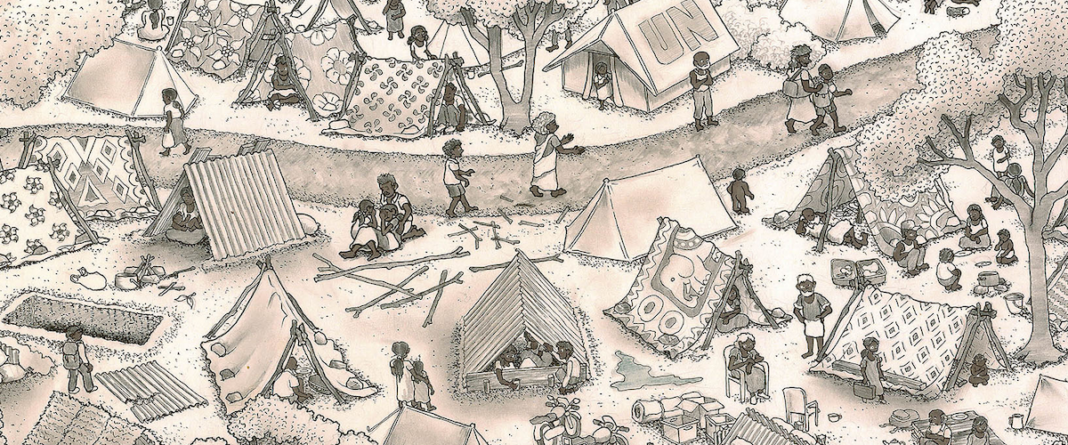

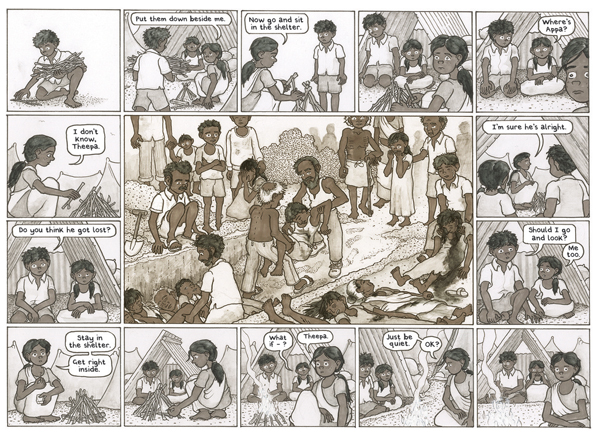

It’s three years later that, during a visit from Rajini’s sister, Priya, and the return of a wounded soldier Jagajeet, the island is hit by a devastating tsunami, which killed nearly 300,000 people and in the middle of a longterm civil war, created hell on earth for the people who survived. Chempiyanpattu is completely destroyed and the survivors find themselves living in a designated relief camp there, with hundreds of tents housing refugees.

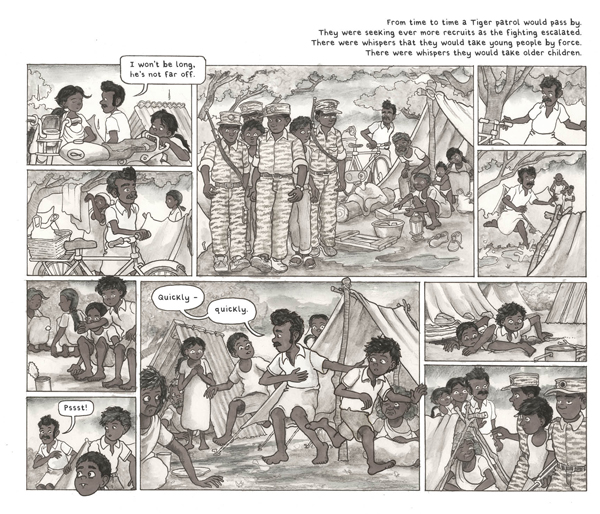

The town slowly looks to rebuild, but invigorated tensions between the government and the Tigers leads to forcible recruitment by the latter and an escalation of violence that sends the population of Chempiyanpattu fleeing. Flight and terror and trauma and violence and danger are the only constants the Ramachandrans and the Chologars are going to have in their lives for years.

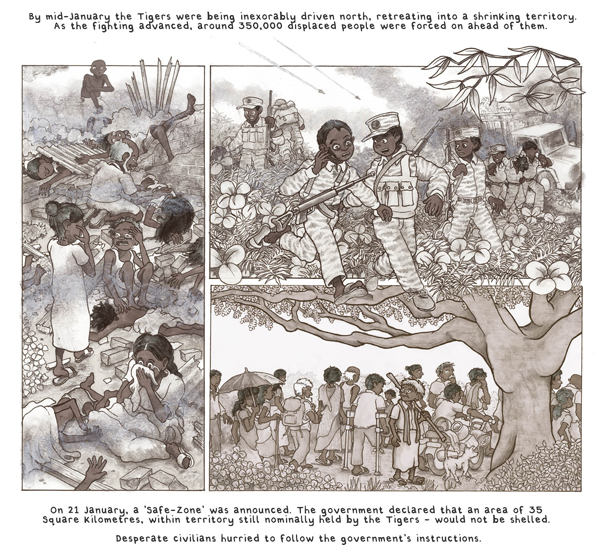

Dix and Pollock devote what follows in Vanni not just to Antoni’s journey, but to the various threads within the families that the conflict creates as people become not only displaced from their home, but from each other, and the disintegrating situation turns into one of desperate survival alongside scores of other people in the same situation. Fueled by meager food availability, living in squalor when they are allowed to get rest, and spending most of their lives on foot, fleeing from violence, the sweet scenes that dominated the beginning of the book are torn apart by a vicious war, and the love between family members proves to be not enough when facing repeated, violent blows from the strong arm that constitutes the flow of human history. It’s a piling-on of hopelessness and horror, bolstered only by the dignity of the refugees that Dix and Pollack follow in their narrative.

At the same time, it’s a testament to human dignity. Even as Vanni covers the wider vista of Sri Lanka’s horrible struggles, it takes the time for the smaller moments, both in times of happiness and terror, and it’s the link between these extremes, and the intimacy of what depicts them, that shows the strength of the survivors of these horrors.

Vanni is an immersive experience like few I’ve encountered in graphic novels. In chronicling a war, Dix and Pollack have chosen to focus on the victims, the by-standers, and examine the excruciating, nearly endless pain and terror they endure in the name of political battles. Pollack’s artwork is rich in detail of the lives these people live and the disasters that befall them, but never depicts the violence in an exploitative way, nor focuses on individual people’s personal pain in a way that seems manipulative.

Pollack also takes care to frame the drama and action to be inclusive of the community, rarely singling out one person, and always providing the context of the land. The destruction of humanity is one that benefits from connections rather than individuals. Communities are destroyed through war. Families. Pollack’s artwork is always staged to keep those threads in mind. No one is alone in the horror and that’s the most terrible thing of all — you have to watch other people go through what you are going through.

What’s impressive, though, is that if Vanni does the important work of building empathy, it doesn’t do it at the expense of actual information. Amidst the huge weight of the emotion, the circumstances of the conflict are still covered clearly, providing a definite entry point for further understanding. If you don’t know much about the hardships in Sri Lanka, this is an amazing primer in that the history imparted are not separated from personal tolls it took on those swept up in it. Altogether, Vanni is an immensely impressive, and utterly heartbreaking achievement.

Comments are closed.