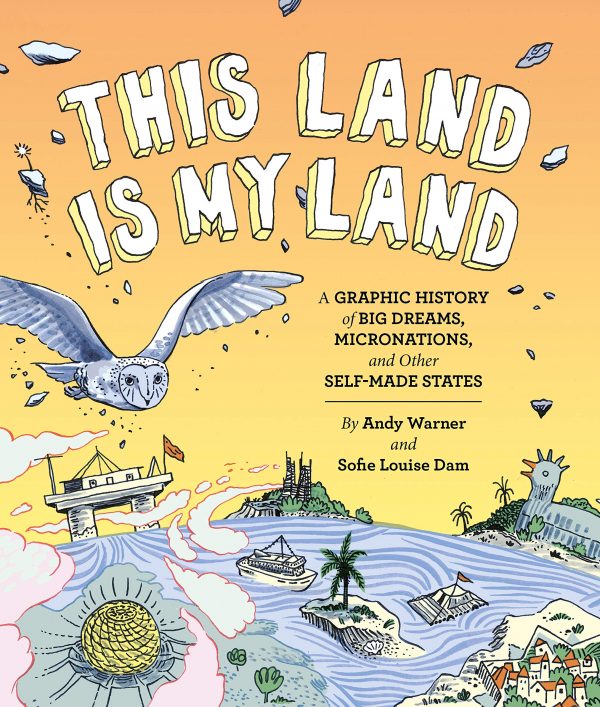

This Land Is My Land

Written by Andy Warner

Illustrated by Sofie Louise Dam

Chronicle Books

If I said that I was a supporter of New England secession, that might be strong, but it’s fair to say I’m a sympathizer, and I’ve had plenty of moments where my passion for it rises — at least in my own mind or on ineffective Facebook status updates. What sets me apart from the people in This Land Is My Land — and this is no doubt the same for plenty of others as well — is that if I even get to the point where I’m laying out in my head the actual plan of how it would work and what it would be like, I remember that each seemingly perfect solution creates a number of other problems that you didn’t predict.

In secession, though, you are at least seizing something that already exists and just moving it apart from the thing it originally existed within. In its focus on entirely new nations, This Land Is My Land maps out efforts to create something from nothing — typically no systems, no resources, and no sustainable connection between the people involved in fashioning out these independent states. And yet you have to admire those mad people who set out to make them work. Well, not all of them, but at least some of them, because while it doesn’t happen often and it doesn’t happen cleanly, those are the types of people who spark change and originality in the world. Outsider nation builders don’t often see victory, but they make life more interesting.

This Land Is My Land divides into five basic types, and sets about recounting several examples of each throughout history, including some more recent versions. And some of them can actually be counted as a success, but spoiler: the ones that work are typically the least complicated efforts.

This Land Is Your Land is a compendium of dreamers, though some of them are obviously scalawags. Warner and Dam do a good job at embracing the eccentricities of these people without making that aspect a negative. In fact, for many of these folks, their offbeat behavior and beliefs, and their place on the margins of whatever society they live in, are their strongest traits. And some of their oddness does lead to a larger positive for that society, often resulting in the person not being required to remain on the margins — though sometimes they choose to because that is not only how they’ve been made to live, but how they choose to live.

But it’s in being able to transition from existing merely as a fringe group to one that is able to formalize and interpret the appeal of its utopian vision to outsiders that seems to lead to success most often. For instance, in the Intentional Communities section, I notice that one requirement of devising and building such dominions is an already well-established embrace of being an outsider. This means well-established life choices, like those of the pirates of Libertatia or the particularly fascinating traveling Lesbians of the Van Dykes, for which is pointed out that a gay person being “out” was more than sexuality, it was a radical act.

But any outsider stance can be qualified as a radical act, not just sexuality, and groups like the Van Dykes, or Freetown Christiana in Denmark, a converted military base which still exists, could ever progress past the radical and into a realm that encouraged diversity and debate.

That’s also the case for Oneida, NY, which still exists but was once the vision of John Humphrey Noyes, a Christian heretic who believed it was possible to build a paradise on Earth. It turned into an incredibly relegated community, famed for its silverware manufacturing, which became its focus instead of spirituality and paradise following Noyes’ departure. The silverware was probably a better bet.

Chaos seems to be the inevitable end to many of these efforts and Sealand was in a constant state of chaos. It was birthed in the 1960s from enterprising pirate radio dee-jays who commandeered the abandoned HMS Fort Roughs in England in order to counter BBC programming with rock and roll. It turned into a war between two dee-jays, resulting in one promptly proclaiming a principality. Spoiler alert: The story doesn’t get any saner after that, provoking an international incident.

But sometimes things do work out, like in Auroville in India, which is situated around a giant golden orb and the legacy of guru Sri Aurobindo and his French wife Mirra Alfassa, who became known as the Mother and was the visionary behind the city. The citizens of Auroville post-Mother were even more visionary in that they gave the city a fighting chance by seeking government assistance in its management, establishing a fringe society with official approval, a rare thing indeed. The Temples of Humankind, an intricate underground complex built into the foothills of the Italian Alps, also allows tourists and, like Auroville, enjoys official recognition.

The Divine Kingdom of Sukrani is an incredible success story. A massive rock garden in India, it was built by Nek Chand, a Pakistani refugee and former road inspector. Fashioned in a forgotten gorge from reusable garbage he collected, his project of 18 years not only survived government threats once it was discovered and embraced by the community, it became a sanctioned public park that he was paid to maintain and expand until his death in 2015. Sometimes things do go right.

Oyotungi African Village in South Carolina is a bit more curious, though it did survive somehow. A relic of the Black Nationalism movement, it still exists. In some ways, it’s like an Afro-Futurist version of Plimoth Plantation, with the village’s culture borrowing from the Nigerian Oyo Empire presenting more of an immersive recreation that allows tourists.

The Principality of Hutt River is a mixed success. It was established in Australia in 1970 by five families of farmers in protest of government regulations of wheat farming. The central figure, Leonard Casley, proclaimed himself monarch of the principality in order to take advantage of a loophole in the law. The principality still exists but as a disputed territory. And Palmanova, which began construction at the end of the 16th Century, a project by the Republic of Venice to create a utopian city-fort specially designed for harmonious living and effective military defense, still exists. It’s not a utopia, though. It’s just an oddly built city.

There are plenty of one-man disasters in the book, singular visions by massive egos that are fated to fail, often spectacularly. Henry Ford might be the most notable person to fall victim to this problem. He was obviously very successful with many of his ventures and transformed American manufacturing. But his success hinged on his ability to call the shots without dissent. He applied this method to his vigorous push of Anti-Semitism and also his creation of Fordlandia in Brazil, partly as an attempt to bring American values to a created community in South America, partly to get cheaper rubber for tires. The dream fell apart amidst rebellion, but there are still Brazilians living in Fordlandia. Ford’s historical legacy, meanwhile, has been notably tarnished thanks to all the Anti-Semitism.

Other tycoons tried to create their own versions, but never even got as far as Ford. Razor magnate King Camp Gillette had plan for a self-contained city in Upstate New York called Metropolis, but never got it going and spent most his money on a crazy mansion in Santa Monica. And Peter Thiel was part of the Seasteading Institute, which didn’t really go anywhere. Rose Island was an attempt by a rich Italian architect to create a tax dodge by declaring his offshore home to be an independent country. That lasted about a year.

Ernest Hemingway, whatever else you might consider him, was a big thinker, but so was his brother Leicester, who tried hard at a literary career but failed … until Ernest shot himself in the head and Leicester wrote a memoir about him. That earned Leicester a ton of money to found his own country and one of the more fascinating historical oddities in the book, New Atlantis, on a 240 square-foot bamboo raft in international waters off the coast of Jamaica, which highlights the fact that micronations require capital — and even with it, the ending of a micronation and its founder can be tragic. No spoilers here.

There’s also the story of Operation Atlantis, which centers around Ayn Rand fan Werner Stiefel. He bought a motel in Saugerties, NY, in 1968 and offered it as a free place to live for Libertarians who would help build a ship destined for the Caribbean in order to create a “stateless utopia.” A series of calamities ensued.

And then there’s the weird guy from Virginia who tried to make his daughter a princess by claiming possession of legally independent land between Sudan and Egypt. He wasn’t very organized, though. Similar is Liberland, a disputed piece of land between Serbia and Croatia that a guy named Vit Jedlicka has declared a free republic. Jedlicka’s tried to enter the country with followers, though Croatian border patrol has so far prevented that from happening.

It’s rather gracious to refer to Tama-Re as a utopia, failed or not. The land in Georgia was populated by a group led by a Muslim heretic with several names who preached about aliens, claimed ancestry to Native American tribes, built pyramids and attempted to run casinos there, and was generally a con man. I guess it was a utopia to him.

At least there is the still existing North Dumpling Island is ruled by Segway inventor Dean Kamen, a.k.a. Lord Dumpling, who seems like he has a sense of humor at least.

Many of these efforts revolve around artwork, often massive visions that could never be contained in any gallery or museum since they typically require significant alteration to the landscape. In the United States, there’s Frank Van Zant’s Thunder Mountain Monument, a massive work commemorating the Native American genocide. It was briefly a hippie commune, but mostly the lonely haunt of a sad man.

More inspiring is Ra Paulette, who focused his creativity on digging out caves in sandstone inspired by Mexican teenagers doing the same. Paulette’s created numerous caves with intricately beautiful carving work on their walls and continues to do so well into his 70s and despite accidents.

Some very touching examples appear in Asia. Xieng Khuan and Sala Keoku are tributes to human perseverance and survival, sitting on each side of the Mekong River, one in Laos and one in Thailand. They are the work of Bunleau Sulilat who began work on the Laos sculpture during a communist insurgency. Fleeing to the other side of the river, he set about on a companion sculpture garden that he worked on for 20 years, until his death. There is also Song Peilun’s Yelang Valley project, a sprawling and still-in-progress sculpture tribute to the Guizhou culture which has disappeared since China has modernized.

Swedish artist Lars Vilks has a more difficult situation, having created the micronation of Ladonia in order to save his massive outdoor artwork from the Swedish government, but now boasts over 20,000 citizens, which any of us can feel free to become one of.

The Gay and Lesbian Kingdom of the Coral Sea Islands amounted to a hilarious and glorious piece of performance art. It was a protest against the Australian government’s refusal to legalize same-sex marriage that saw a group of protesters sailing on the Gayflower to an atoll off the Australian coast. Proclaiming an emperor and automatically making every LBGTQ person in the world a citizen, it existed for 10 years.

The Arizona Mystery Castle is aligned with this art designation, but only just. It was built from one man’s vision in tribute to his daughter, but mostly exists as an oddity rather than for any high-minded purpose but the story about it is fascinating and dark. The exact opposite of dark is Gereja Ayam in Java, better known as the Chicken Church. It’s supposed to be a dove, but locals didn’t think so, and the venture is more a farce than a tragedy, a huge, strange clump of outsider art.

If there’s one completely inspirational story in the book, it’s that of Freedom Cove, or more specifically artists Catherine King and Wayne Adams, who built a floating art studio that, once they began to live in it, was expanded beyond your wildest imagination, but not theirs. Its a sweet story of the possibilities created from love, artistry, and pluck. One of the differences between it and all the other stories and the one that makes the project seem healthy is that it is the effort of two people on equal standing, with equal goals, realistic and slightly humble demands of the world, and a devotion to the other person, not just themselves. And perhaps that’s the lesson in the best way to build a workable utopia.

What Warner and Dam layout in This Land Is My Land is a rich, amusing, and pretty thorough survey of people who take the idea of carving out a niche for themselves much further than the majority of us ever go. In some cases motivational, in others preventative, it’s a good example of what history comics can do — amuse and inform grown-ups, and for kids, maybe help build a workable bullshit meter to avoid disaster and swindle, but also maybe instill the sense that they don’t necessarily have to do things like society suggests. There are other paths.