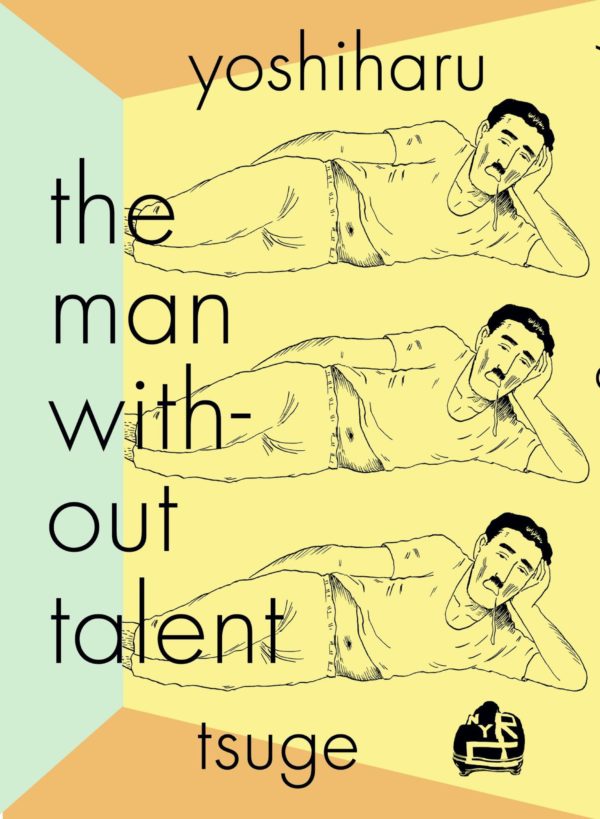

The Man Without Talent

By Yoshiharu Tsuge

Translated by Ryan Holmberg

New York Review Comics

The Man Without Talent is not exactly an autobiography, but as revealed in translator Ryan Holmberg’s essay, it contains portions of nearly exact truth mixed with other portions of mostly emotional or philosophical truth that get to the core of aspects of author Yoshiharu Tsuge’s life without being bothered by the actual details. Originally serialized in the Manga magazine Comic Baku in 1985 and 1986, The Man Without Talent captures a time in Tsuge’s life dominated by a struggle that’s hard to define, but when he was separated from his creative endeavors, possibly out of self-doubt, and given to reckless schemes in order to get by in life economically.

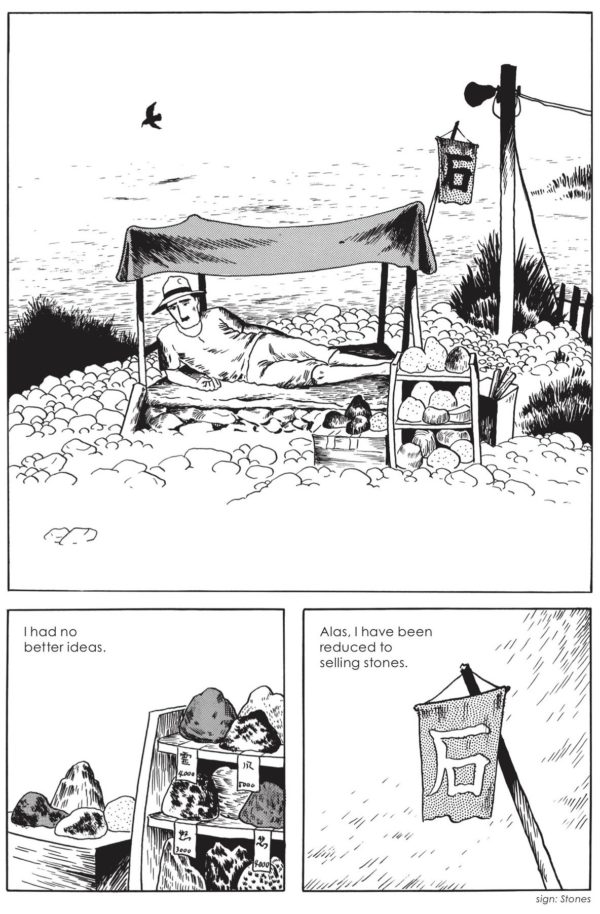

If the decision to walk away from a reliable way to sustain his family’s life represents the choice of a loser to most in the modern world, there’s something in the way Tsuge presents it that makes it feel like a philosophical choice of considerable importance. When we meet Sukezo, Tsuge’s fictional alter ego in the book, he’s selling stones on the shore of the Tama River beneath a makeshift flimsy shelter from the sun.

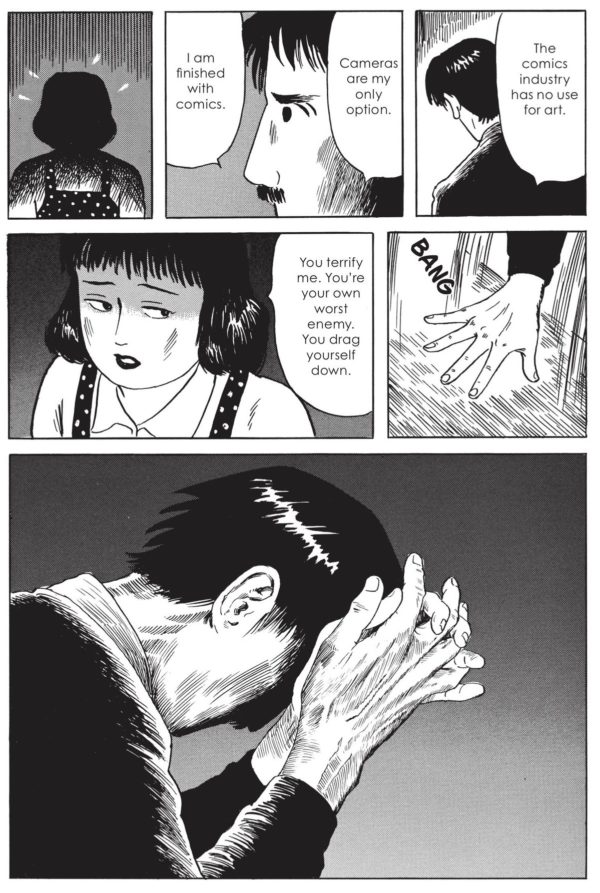

In his own words he’s been “reduced to selling stones,” lamenting that he “had no better ideas,” but as the narrative of his life unfolds, it partly seems like he doesn’t want better ideas. In the first chapter, Sukezo rattles off a list of past ventures, including his work in comics, as follies best put behind him, as he wanders through his present fog of ambitionless meandering, apparently uninterested in altering his course if only to please his wife.

But even stones prove to be too complicated, there’s so much more to it that picking them up and asking money for them. There’s a system to commandeer the lazy indulgence that dictates what you sell and how you sell it, which creates standards of demand and offers drama that Sukezo would prefer to avoid.

Sukezo interacts with other men who seem to be on similar journeys in their lives, trying to eek some living because reality demands it of them, but refusing to embrace any practical method of doing so, which leads to more drama, more dissatisfaction. But that may be the point, you realize, as Sukezo chats with the owner of the bird store that no one seems to pay attention to.

If there’s one common aspect to the stories that Tsuge tells in The Man Without Talent, it’s Sukezo’s largely unconscious insistence that his work remains separate from his family. In the rare times that he mixes the two, disaster usually unfolds, and Sukezo’s knee-jerk is to not even reveal his reasoning about work to his wife in an attempt to keep something for himself — if she’s trying to commandeer what he does for work, then he can at least keep his thought process on the subject to himself.

It all amounts to Sukezo’s attempt to maintain a sense of self as he becomes more a part of a unit where others rely on him. This becomes more apparent in the final chapter, “Evaporation,” in which Sukezo speaks with a bookseller and learns not only his personal story but more about the idea of being ignored by the world as a victory, of fading into the background as a valid goal, perhaps even noble.

At no point does Tsuge ever seem like he expects every reader to enter into the same mindset as his lead character, but he does seem to understand that Sukezo’s approach to life could possibly elicit approval and disdain, and perhaps both reactions from a single reader. That’s because The Man Without Talent is as much about what you owe yourself versus what you owe others, and how much of the world’s expectations you should allow to guide your own life, as it is about anything else. It’s easy to dismiss the character of Sukezo as selfish, but the questions asked by his life are questions that any of us ask ourselves, and Tsuge allows these conundrums to manifest within his own context, putting himself out there both as straw man and devil’s advocate so that we don’t have to do the same with our own thoughts and experience.