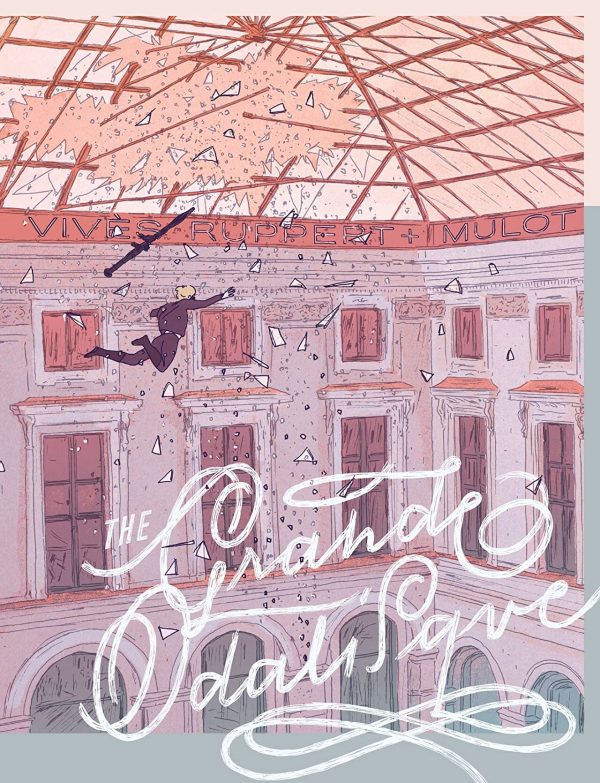

The Grande Odalisque

By Jerome Mulot, Florent Ruppert, Bastien Vives

Translated by Montana Kane

Fantagraphics

The word “badass” has become tiresome in its overuse, and yet that’s the only word available to me to describe the main characters in The Grande Odalisque. Alex and Carole, best buddies and daredevil criminals, have absorbed every meaning of that word, including the inevitable nihilistic outlook that eventually arrives in a badass lifestyle. Crime is the first step, and then transgressive, boundary-pushing crime. From there it moves onto self-destructive, spectacle-dominated crime, and then all the ways you reward yourself to excess for your exploits. Escaping the job needs over-the-top solutions and they come via drugs, sex, booze, partying, and general over-indulgence in any aspect you can think of. Next thing you know, you’ve disassociated from normal human culture. Such is the path of the badass.

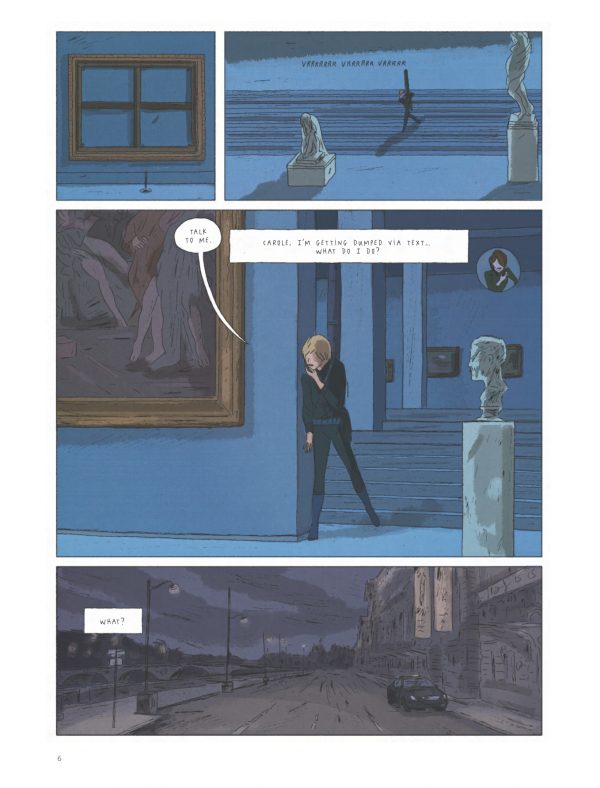

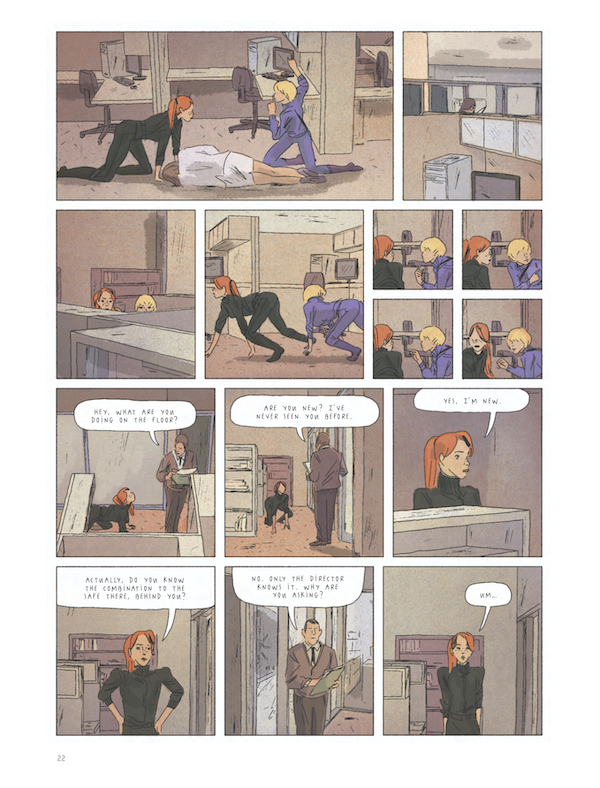

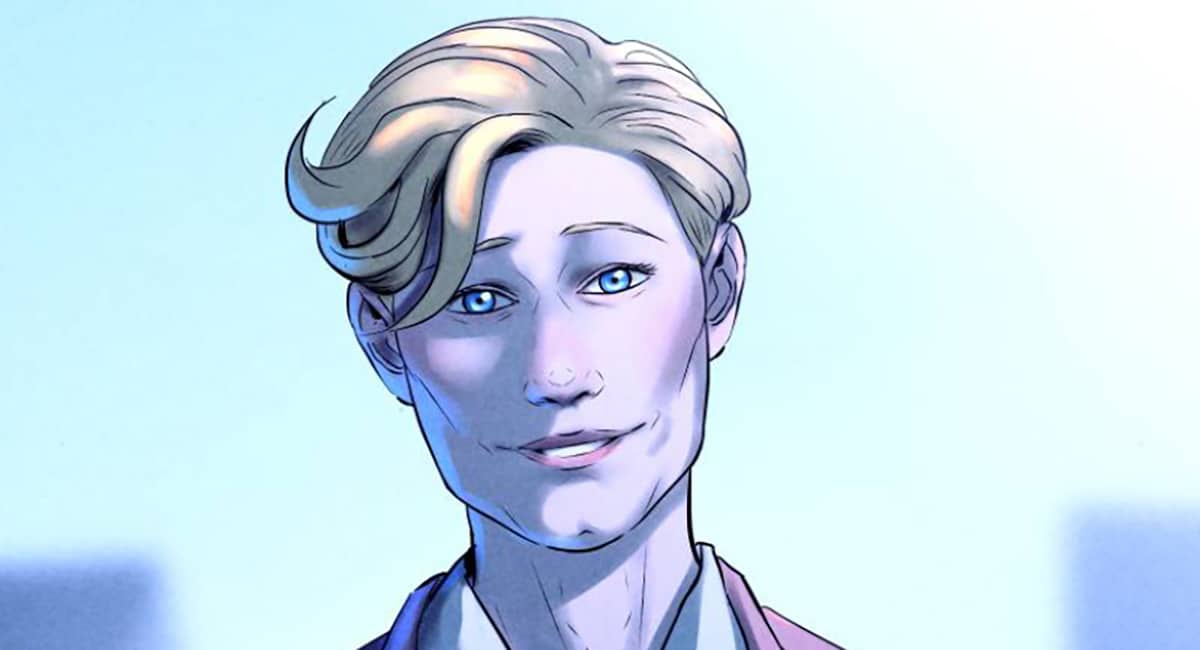

At least Alex and Carole enjoy their life together, robbing museums and playing out a gender-swapped buddy movie, but some of the professional cracks are beginning to show, including tension with a business associate who finds them clients and careless moves during jobs, especially by Alex, who gets dumped by phone in the middle of a job with nearly disastrous results. Maybe they need someone else on their team, Carole suggests. Alex, the more self-destructive of the two, isn’t thrilled with the idea, and it’s seldom that fiction presents a tight team of two that survives the arrival of a third party. As it turns out, though, it turns out less destructive than just complicated.

When self-destruction is part of the narrative mix, it’s likely that something’s going to fall apart, but the beauty of The Grande Odalisque is that the interpersonal is so clearly mixed with the characters’ profession that the overwhelming concern they need to take with getting a job done right naturally seeps into the care they take in their own friendship. That’s what sets it apart from so many male-oriented buddy adventures, an acknowledgment of the bond between the characters and its importance to multiple aspects of the story.

The effect of this clarity of emotional portrayal is that the potential clutter of other aspects of the book is also swept away in the presentation. The dialogue — I think this is the province of Jerome Mulot and Florent Ruppert — is kept uncomplicated while depicting anything but, and even in moments of information dump manages to maintain clarity and not pile on too much. It’s one of those less-is-more triumphs.

The art, which I think also involves Vives and Ruppert but is where Bastien Vives definitely enters the equation — the creative lines are blurred — manages the same feat, especially in the action scenes which offer potentially overwhelming sequences taking place in grandiose locations. The depictions are kept simple and clear and therefore are pretty exciting and quite elegant, like violent ballets.

The Ingres painting for which the book is named was controversial in 1814 for its depiction of a nude woman that takes liberties with the realities of anatomy and has been said to imply a deep inner life for its subject despite the fact that her job, concubine, is merely for the pleasure of men. That context adds an undeniable feminist edge to the book, as does the fact that this is the same painting that feminist art collective the Guerrilla Girls used for their iconic poster placing a gorilla mask on the Odalisque figure and asking, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?”

The answer, it turns out, is no. They can get in other ways, like armed robbery. And that’s the kind of conclusion that makes The Grande Odalisque as audacious as its characters.