The Eternaut

Written by Héctor Germán Oesterheld

Illustrated by Francisco Solano López

Translated by Erica Mena

Fantagraphics

Originally serialized from 1957 to 1959 in the Argentine magazine Hora Cero Suplemento Semanal, The Eternaut has become somewhat of a phenomenon in its home country and beyond those borders in countries such as Spain, Mexico, and Italy. It was reprinted in its own magazine in 1961, and in 1969 received a reboot from author Héctor Germán Oesterheld and new artist Alberto Breccia, and a sequel in 1975, with Francisco Solano López.

Other authors have continued the series following Oesterheld’s disappearance in 1977. Oesterheld is believed to have been held in jail by the country’s dictatorship until his death, a fate shared by his four daughters and their husbands.

Though the work became more politicized with each iteration and to an outside eye they might zoom by in this first version of the work, Oesterheld uses specific moments in the story to hearken to the unrest in the country in the late 1950s, during Juan Perón’s first ruling era in the country, followed by an overthrow and military dictatorship. Oesterheld also frames Argentina as a place cut off from the wider world, but its fate forever linked to the actions of the superpowers in domination.

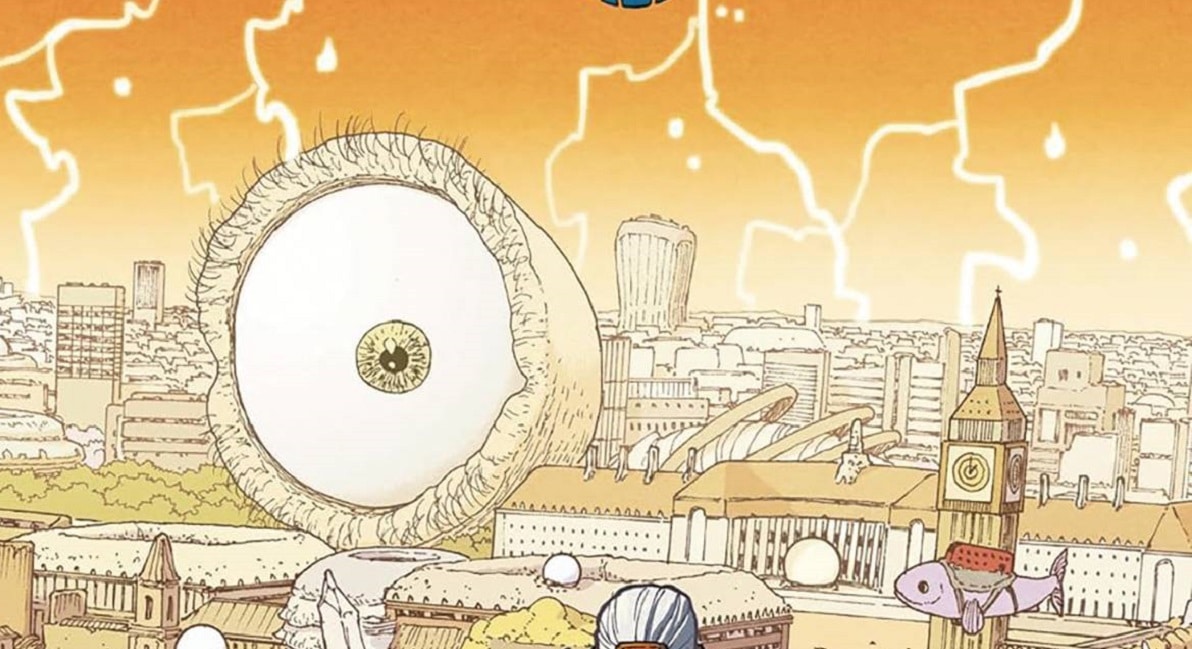

The Eternaut manages to reflect these situations, and, more importantly, the personal reactions to them on the local level, in a science fiction setting that is both heady in its presentation even as it provides some bombastic action scenes. Opening with the Eternaut’s sudden appearance in a cartoonist’s home, the book is a long explanation by the Eternaut to explain how exactly he had manifested there.

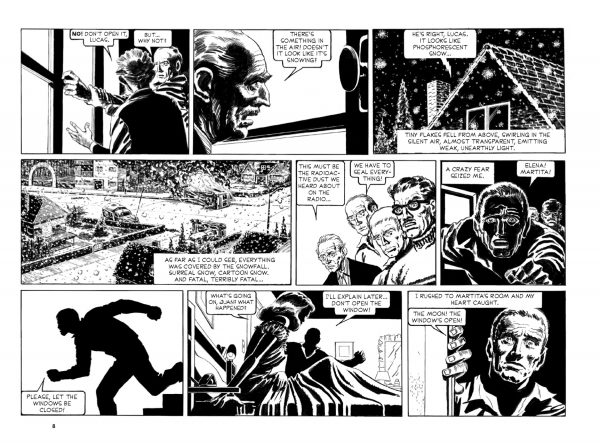

The story begins with an innocent gathering between the Eternaut — real name Juan Salvo — between friends for a card game. A strange snowstorm begins to pummel the area and observation shows that it isn’t snow out there, it’s some strange substance causing immediate death to anyone who comes into contact with it. Salvo’s wife and daughter, and his friends are trapped in the home and need to use their ingenuity in order to figure out a way to leave it and gather supplies to survive.

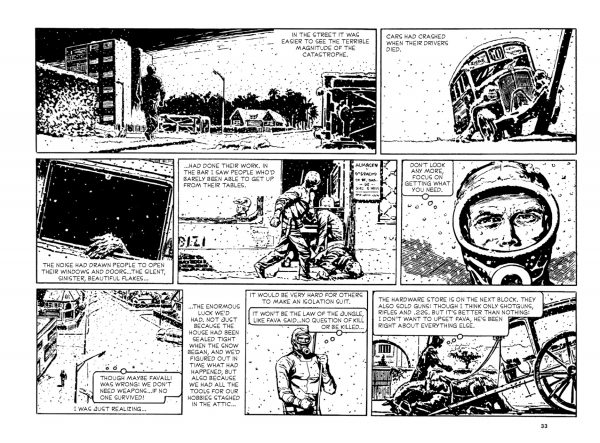

It’s a situation as isolating and unnerving as any you’ve seen in the ten million zombie apocalypse stories that have been told over the last decade or so, but the helplessness of the situation elevates the terror the characters feel. But The Eternaut is not content to stay fixated on one horror, one situation, and elongates into a fight for survival that takes into account some classic ‘50s science fiction tropes and either uses them to solid effect or warps them into bizarre absurdity even as it keeps its eye on the down-to-earth political struggles faced by plenty of common people around the world, though significantly here, the citizens of Argentina.

I won’t rattle off any further plot points, because it’s the epic quality of The Eternaut, as realized through its serial format, that is part of its appeal. So is its relentless seriousness, as well as the non-jaded approaches of the characters in solving the conundrums here. In this way, it’s like watching an old episode of Doctor Who from the 1960s, just refreshing in its tone (just like Oesterheld’s later work Mort Cinder, also published by Fantagraphics), with López’s old-style adding the charm, as well as heightened alarm. His rendering of Buenos Aires in a state of apocalypse is chilling and effective, but also fun — this is a comic strip serial after all.

The Eternaut has me intrigued and I’m hoping that English translations of the later versions of this story are in the works from Fantagraphics. Cautionary tales in response to authoritarianism are useful these days, but too often just speculative not only in their mechanics but emotion. It’s fascinating to see a political activist living through a situation of deadly political oppression translate his experience into something for ordinary people to absorb.

Some comments:

The cartoonist at the beginning, Germán, is Oesterheld himself. By 1957, when El Eternauta was written and became being published, Perón was no longer in charge. (He was overthrown in 1955.) Argentina in 1977 (when Oesterheld “disappeared”) was much different from what it was in 1957. By the time of the “first” Eternauta, Oesterheld was a “peronista”, but not really a committed activist. (By the way, he was mainly involved in the ’70s because of the involvement of his daughters.)

Comments are closed.