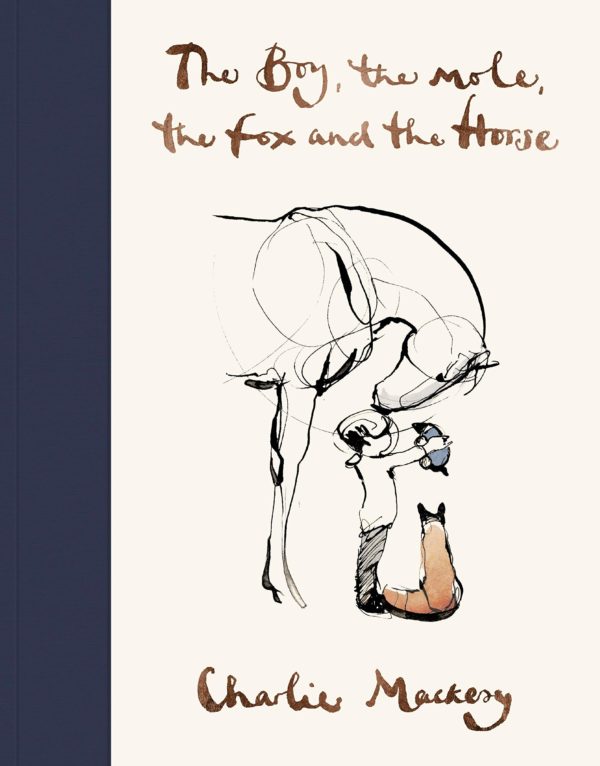

The Boy, The Mole, The Fox, and The Horse

By Charlie Mackesy

HarperOne

It’s been a hell of a year in some unprecedented ways, and so it seemed appropriate that The Boy, The Mole, The Fox, and The Horse should not only make its way into my life as a Christmas gift from a lovely friend of ours but should speak in some strange way to the hell of a year as an antidote to it, and therefore compel me to review it.

I know there have been worse years in modern history and 2019 pales in comparison to, say, 1918 or 1942, both blood-drenched years, or stretching further back, 1492 or 1619. In some ways, the awfulness 2019 is manifested at its fullest strength in existential terms, personified in physical form by our elected president, whose continual brutality in the form of words creates people devoted to the only kind of effective resistance positive, short of an actual armed revolution — a barrier of kindness.

I am struck by something that newspaper cartoonist and artist Charlie Mackesy writes midway through The Boy, The Mole, The Fox, and The Horse, his first book. The Mole says to the Boy, as they sit face to face with each other, “One of our greatest freedoms is how we react to things.”

This is the ultimate truth as I have understood it in my aging years. You actually can’t control what other people think about anything, from comics to the worth of other human beings. You can try to convince them otherwise, but you can’t control them. The only thing you have any dominance over is yourself. The only thing that you can possibly utilize in navigating the awfulness contained in the world — or unleashed by it — is what you think of it. Your reaction, which sets into motion what you do or don’t do, is your power.

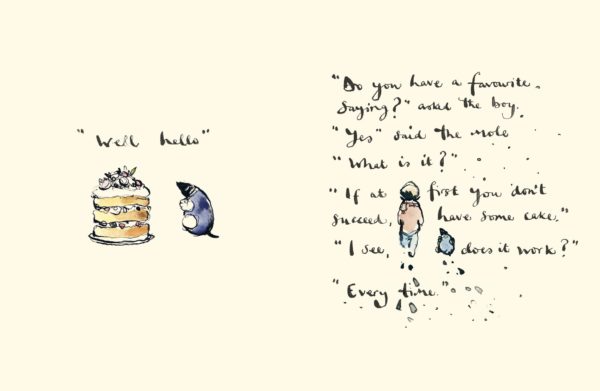

That’s the essence of what The Boy, The Mole, The Fox, and The Horse is about. There’s very little within it that could be qualified as a story beyond “a group of creatures meet in the wild, wander around together and have a meaningful conversation about self while the Mole reveals an obsession with cake.” But it could also be described as “a group of creatures meet in the wild and exercise their greatest freedom.”

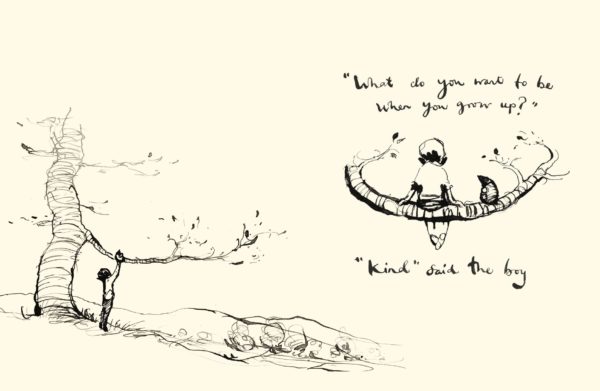

What unfolds is something more akin to a zen journey than anything else, where the characters talk with each other about learning to position themselves calmly in the world in such a way that kindness becomes their guiding principle, with others and especially with themselves.

While this takes the form of vanquishing guilt in the visible dialogue, the characters also take the time to reveal little bits about themselves and take these quiet revelations as ways to formalize their commitment to kindness and to affirm their own worth to themselves as supported by the other creatures going on this journey of emotional evolution. As these moments build, there’s another central message that unfolds, the idea of support, of making yourself available to other people and accepting what other people wish to offer you.

The conversations that Mackesy presents here all unfold in a Winnie the Pooh way — not the Disney stuff, but the elegant, insightful, philosophical, and witty original writings of A.A. Milne. And as the words demand this comparison, the art itself doesn’t really do anything to move that in another direction. Mackesy’s drawings are beautiful and evoke the work of Pooh illustrator E.H. Shepard.

The real challenge of kindness, though, is the choice of who you direct it toward. I would suggest that the most meaningful kindness as being the most difficult to show. It’s easy to show kindness to those you love. It’s harder to do so to someone who makes you feel threatened. But that’s exactly what Mackesy endorses here with the presence of the Fox, who is introduced as an aggressor to the Mole, who decides to approach the Fox in a gracious way, offering help. The Mole, so often portrayed in the book as a goofy cake obsessive that still has plenty to learn, actually proves early on the willingness to do the hardest work of all.

Look across the chasm that divides you from your perceived enemy, stare directly at your bully or your oppressor, directly at whoever who challenges your prejudices, your stereotypes, your views of the universe, your commitment to the idea that might makes right or that some transgressions make someone less than human or those wielding power don’t deserve kindness, and realize that’s the person Mackesy is challenging you to be kind to.

It’s a radical suggestion, far more so than any revolution or act of resistance, one that doesn’t automatically forgo justice or equality, but rather points to a different way of achieving — and the effort to embrace kindness as your chief tool in conflict says a lot more about you than about the other person and that, I think, is a goal befitting the Mole, which is something worth striving for.