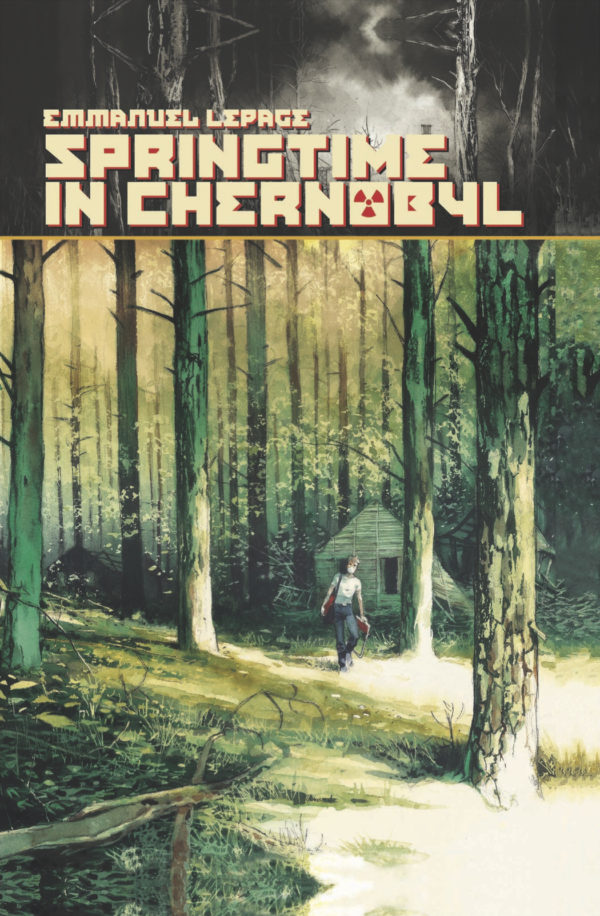

Springtime In Chernobyl

By Emmanuel Lepage

IDW

You wouldn’t expect to pick up a life-affirming book about Chernobyl, but French cartoonist Emmanuel Lepage achieves exactly that in his beautifully-rendered book Springtime In Chernobyl.

Recounting his experience as part of a Chernobyl artistic residency, Lepage goes seeking the monster of Chernobyl. Not a physical thing, but the horror that we all think of when we consider the disaster in 1986, looming in the area in some form all these years later, some proof of what we all hear about.

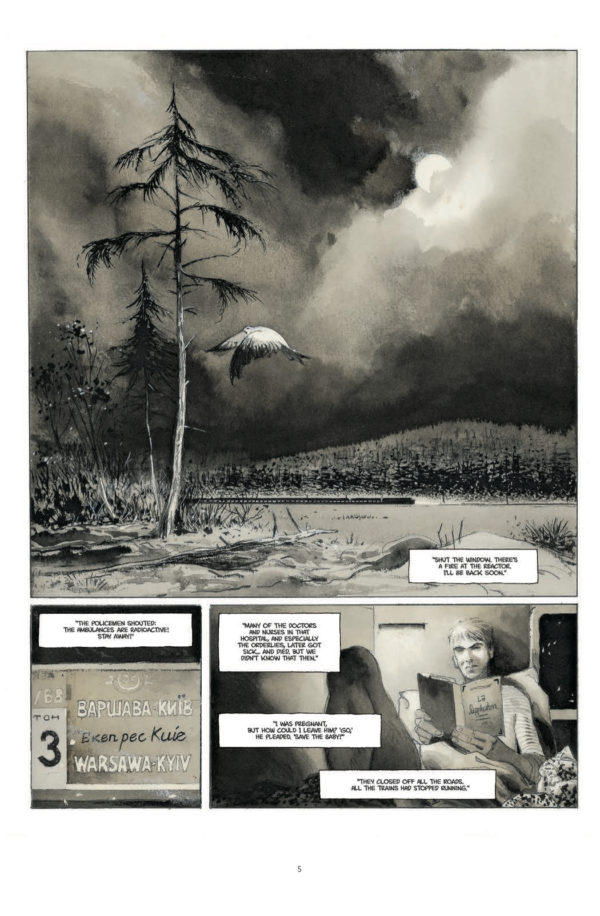

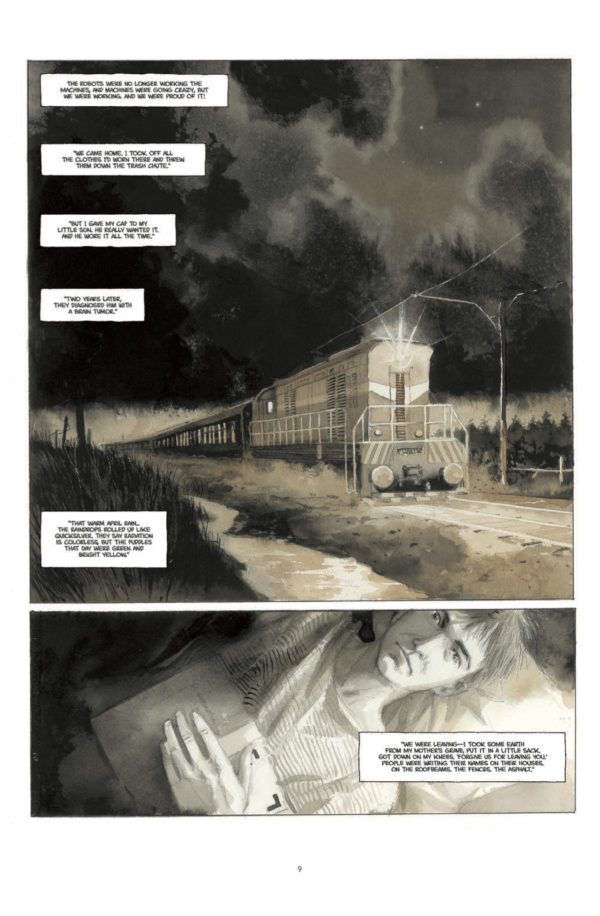

And there’s plenty of reason to expect such a thing. Lepage does a powerful job of going over what happened, both the basic events of the disaster and large toll it took on the people affected. He stages the events in personal terms by including the testimonies of people who faced personal loss because of the radiation, and places the events in also in wider terms, what it meant to the Soviet Union.

It also makes clear the horror that we all take to heart, that we know to be a fact, with dark renditions of the events, as if some shadow has been cast over the people fleeing the area for the lives. By expressing the underlying mood of what happened, Lepage is able to bring the invisible out into our world, to allow the reader to see it draped all around the world he depicts.

But for Lepage, it wasn’t that easy. At one point in the final stretch of Springtime In Chernobyl, Lepage looks around as he tours areas of Chernobyl with his sketch book and wonders to himself, “How to draw the invisible?” He’s talking about the radioactivity that looms, but he might as well be talking about the emotions that are wrapped up around the area as well. Many of them have to do with loss, mostly that of homes and possessions and certainty. Some have to do with the loss of lives, either as the disaster in Chernobyl was unfolding or as it revealed itself later thanks to the invisible poison that sat in the air. And for some, the loss is about the great communist dream itself, as the disaster in Chernobyl heralded its end.

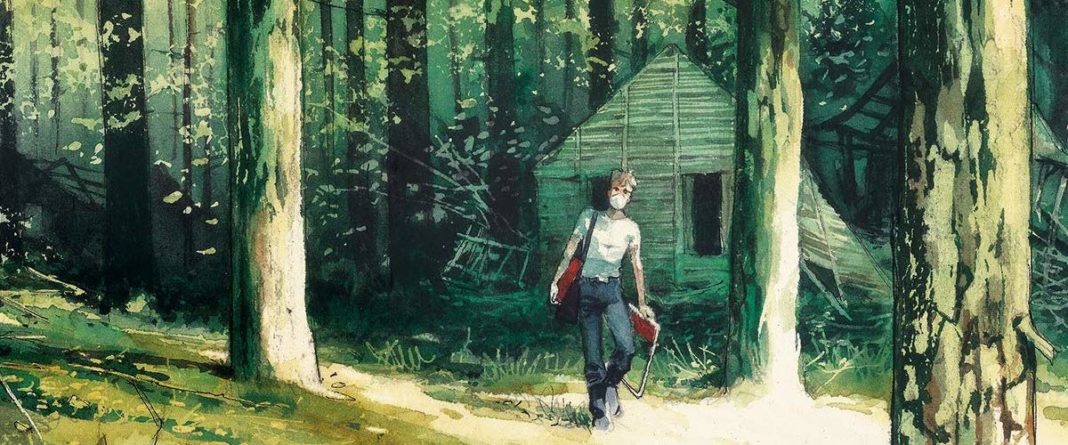

Lepage’s conundrum is also partly that there is a beauty in Chernobyl. There is beauty in the landscape as it is reborn, beauty in the detritus of mankind as it decays. There is beauty in the people they meet who huddle around the area. Within the horror of the story itself, there is beauty in the resolve of those who faced the disaster.

This beauty comes out in Lepages’s simply stunning art as color amidst the bleak, muddy darkness that most of the book lives in. Part of that color is just what he sees in nature when he’s out drawing while the geiger counter click, click, clicks, trying to add tension to the scenes he’s capturing. But Lepage isn’t there to tell lies, to fulfill our expectations of his experience. The color is there in the forests and in the souls of the people who cling onto the area’s borders.

In interacting with those people, Lepage discovers a resolve and even some joy that he didn’t expect. He’s so conflicted with this that he goes out searching for something to convince him that it’s an illusion. Only briefly does he directly confront anything remotely resembling terror, some aspect of the darkness he keeps imagining existing coming to reveal itself and force its way into the work, but again, it’s all a feeling.

Springtime In Chernobyl is superb comics journalism that covers the facts, and Lepage’s account of his residency shows what we think we know isn’t always reality. As he says in the book, he expected to be faced with a disarming bleakness, but as I read his account, I thought to myself how the history of humanity is basically a timeline of one nightmarish disaster to the next, an accuring of millions and millions of deaths in the most horrible ways, and yet here we are. Traumas may get the best of individuals, but as a species, we are resilient and routinely move on, and that is partly because survivors of traumatic events are very often able to do the same themselves. And nature, too, has its own method of reclaiming what belongs to it. In Springtime In Chernobyl, those are the realities Lepage ends up depicting.

Comments are closed.