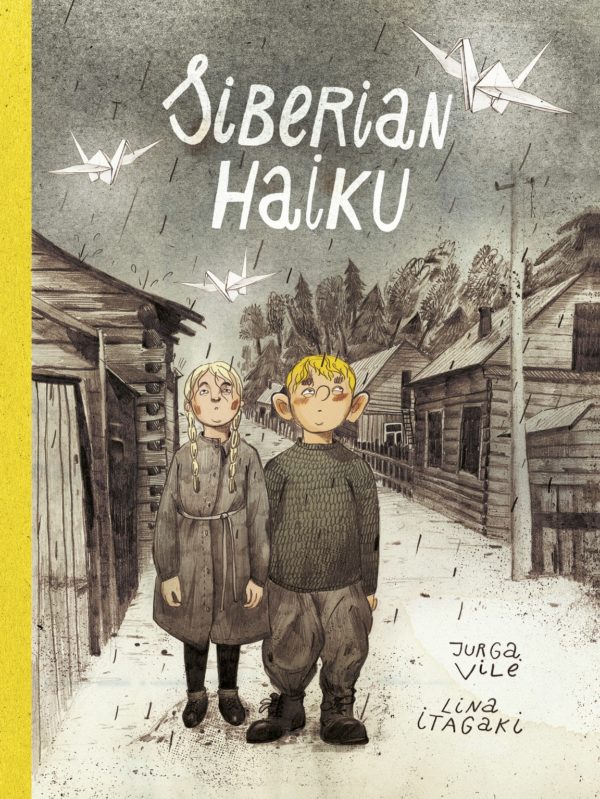

Siberian Haiku

Written by Jurga Vile

Illustrated by Lina Itagaki

SelfMadeHero

Starting in 1941, Lithuanians endured the first of nearly three dozen mass deportations by order of the Soviet government, which occupied Lithuania. Over an 11 year period 130,000 people — mostly women and children — were sent to Siberia and placed in labor camps where they provided what was essentially slave labor and suffered abuse and hardship. Targeted were, according to the Soviets, “anti-State elements agitating against the people’s government,” which included police, union members, and others.

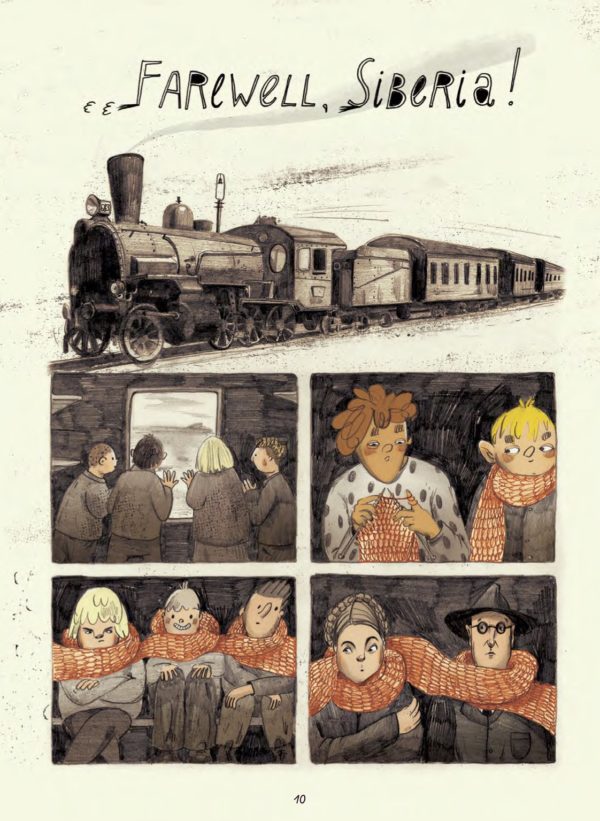

It’s into this situation that Jurga Vile and Lina Itagaki dive with Siberian Haiku, the story of Vile’s father, Algis, who was deported to Siberia with his family in 1941. The story starts at the end though, with Algis onboard “the Orphan Train,” part of an effort on the part of the USSR government to bring back Lithuanian children who had been exiled, specifically orphans though other children were included.

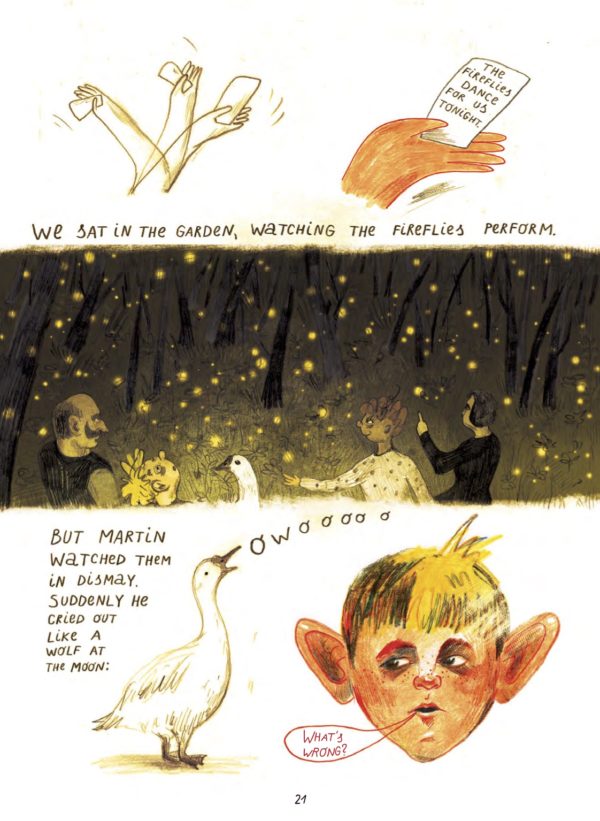

As Algis sits in a darkened train car huddling with other children and nursing his whooping cough, he begins to recount his story by introducing some of the ghosts that follow him around, the specters of those lost on the journey that we are about to experience. When the narrative shifts back to Lithuania before the forced deportments, it’s a charming, almost magical place concerned more with beekeeping and apple growing than anything else. Algis procures a pet goose and dreams about the journeys of flight they will take together, which introduces an element of magical realism that will sit comfortably within the entirety of Siberian Haiku and give it a whimsical edge throughout, though admittedly a pretty dark whimsy.

Though the events in Siberian Haiku are serious, they are through the eyes of a kid and so even when sadness registers, it’s mixed with curiosity, amazement, and sometimes even adrenaline. As the families are rounded up and sent on their way to Siberia, there is an underlying sense of adventure amidst the general trauma. As gloom and tragedy descend upon the families in the Siberian camp, from the point of view of Algis these are just the dark parts of a wider story, the inevitable peril and danger and villainy in a personal fairy tale that is embellished with appearances by the ghost of his goose.

But having that point of view also creates the opportunity for characterizations of others in the family and community that lack the solemnity that could no doubt overtake anyone in that situation. Partly that’s part of a kid’s perception of adults, and partly it’s the adults restricting the more dire moments from entering the kid’s periphery. As a result, the pantheon of townspeople, fellow deportees, and even guards that move in and out of the account are treated not always with the kind of delicacy that results in narrative agendas, but instead, raw honesty that shows that even in tragic situations people are sometimes blasé or goofy or grouchy as well as the more expected reactions.

Itagaki’s artwork is the key ingredient in bringing this world alive. With an illustrative style that is often scrappy and tattered, trading off personal sequences featuring cartoonish, stylized people with more sweeping moments that are inclusive of the larger picture and the foreboding atmosphere that lingers over everyone, as well as the cryptic and surreal sequences of magic realism, Itagaki really fashions an entire universe from Algis’ mind, a mix of the reality he faces every day and the fancies that flutter in his imagination, converging in such a way that Itagaki’s art not only heightens the meaning of the drama but also captures the way in which Algis survives.