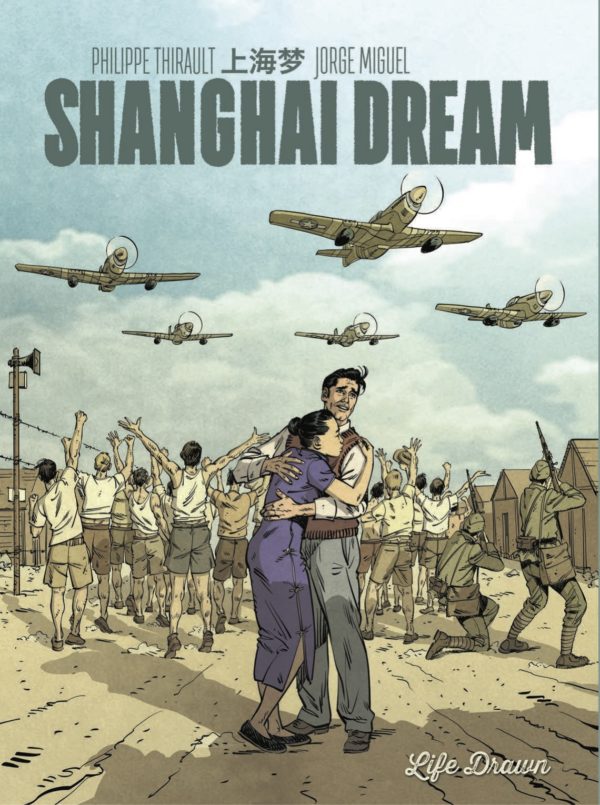

Shanghai Dream

Written by Philippe Thirault

Illustrated by Jorge Miguel

Translated by Mark Bence

Humanoids/ Life Drawn

Portrayals of the Holocaust have found their way into multiple comics forms, but almost always they focus on the Europe. One lesser known aspect of that horror happened in Shanghai, where thousands of Jews fled following Kristallnacht in Germany. In Shanghai Dream, the history of that is captured through a melodrama about filmmaking that manages to evoke the era of film that it portrays while also providing the horrific reality of the times.

Opening in 1938, Bernard Hersch is an aspiring filmmaker in Germany and his wife, Illo, works on a romantic comedy screenplay that Bernard plans to film. But the persecution of Jews escalates and not only does the couple’s dream of filming the screenplay look unlikely, so does the idea of them being able to live out their life in peace — or, in fact, live at all.

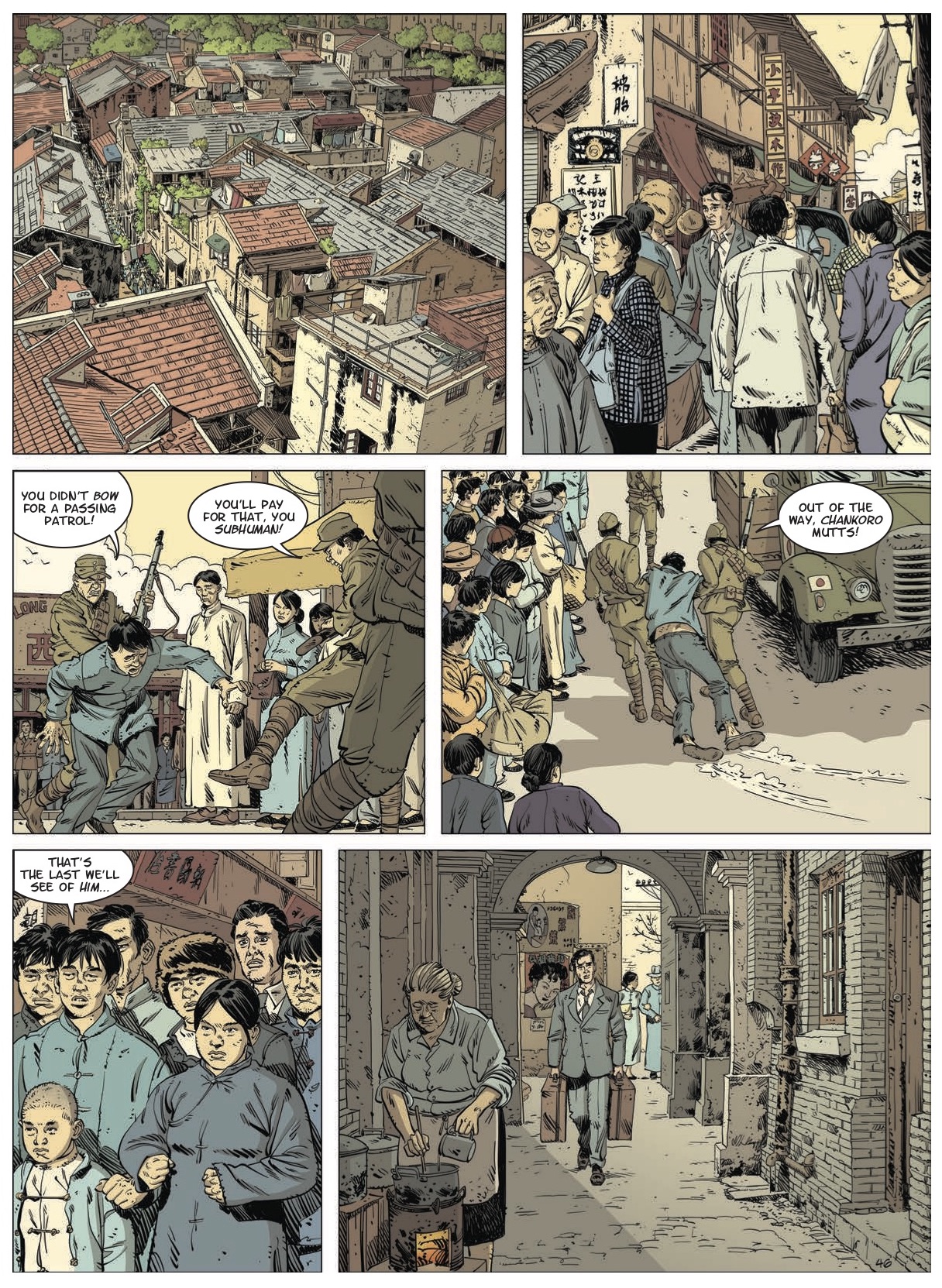

After the terror of Kristallnacht there’s a frenzy of German Jews trying to escape the country, a difficult feat, and Shanghai becomes the focus of Bernard and Illo’s escape. As the only place in the world that did Jews did not require a visa — other than the Spain, then under control of Franco — it was easier for refugees from Germany with no other recourse to flee there. But as Bernard finds out, conditions there aren’t wonderful, and Jews are shuffled into their own ghetto there, with few work options, guaranteed poverty, and occupation by Germany’s allies, Japan.

Bernard has landed in Shanghai without Illo, and much of the book revolves around his attempts to realize her dream of seeing her film on screen, but with concessions made to the situation Bernard lives in. Having to adapt the film to Chinese and reframe it within Chinese locations and culture, Bernard also has to navigate a growing anti-Semitic sentiment from the occupiers that seeks to restrict the Jewish population, thanks to pressure from their German allies.

Shanghai Dream keeps hope alive as it portrays the hardships faced by the German Jews in China, easy to do since the conditions in Shanghai were nowhere near as dire as in Europe, though you have to wonder if things were headed that way, halted by the end of the war. Regardless, the optimistic undertone it allows to flow through the story also reflects the era of film within the story, as well as the screenplay that’s at the center of it. And movie making itself, especially back then, was a pretty aspirational venture. But the book is apparently also based on an apparently unproduced screenplay by Edward Ryan and Yang Xie, and that may or may not also account for the feel-good threads.

While the story is enjoyable, it wouldn’t be half as effective without the art by Jorge Miguel, which does well by its characters but excels at portraying the world around them. Whether in a darkening Germany or a chaotic and fearful Shanghai, Miguel is amazing at the sprawl and the detail of these worlds.

If the book itself is a great way to introduce yourself with a lesser-known corner of World War II history, as well as Jewish persecution, the one frustration is provides is that by focusing on this specific slice of history, it excludes other horror and persecution that the Japanese invasion and occupation of Shanghai was fraught with. As presented, the story is very Euro-centric — no surprise, given that the author is French.

It’s too bad, because if these further aspects were explored and accentuated, there might have been added further dimensions to the story by creating the connections across the persecuted people — which in Shanghai included Americans and British, as well as the occupied Chinese. This could have explored wider truths about the terror of authoritarianism and its effect on diverse populations, and might have been even more spectacular with Miguel rendering it. As it stands, this is an enjoyable, well-realized small tale that holds back a larger, looming backdrop.

Comments are closed.