Paul At Home

By Michel Rabagliati

Drawn and Quarterly

Quebecois cartoonist Michel Rabagliati has established a definite tone of the last couple decades that he’s produced his Paul series, but with Paul At Home, he’s disrupted this comforting aspect. We don’t know it at first as the book opens with Paul, in the same friendly art style, fumbling around a grocery store with his shopping list in hand, and buying some cereal for his daughter Rose.

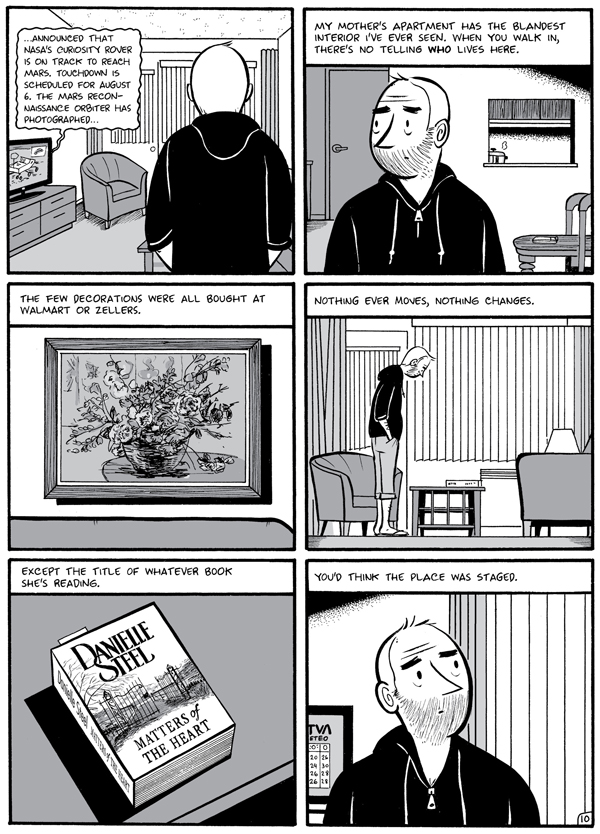

There are a few wistful moments, some angry undertones, but as Paul At Home begins, Paul is on his way to his mother’s apartment, where he goes over her life and we learn about not only her faraway past, but the more recent events, taking us through two marriages, two divorces, and a life of loneliness that has her disengaging from the world. Some hectoring from her reveals that this might be her life, but in context of Paul, it is a warning. Paul is now divorced, not dating, not hanging out with friends, barely seeing Rose. Paul is on his way to becoming his mother.

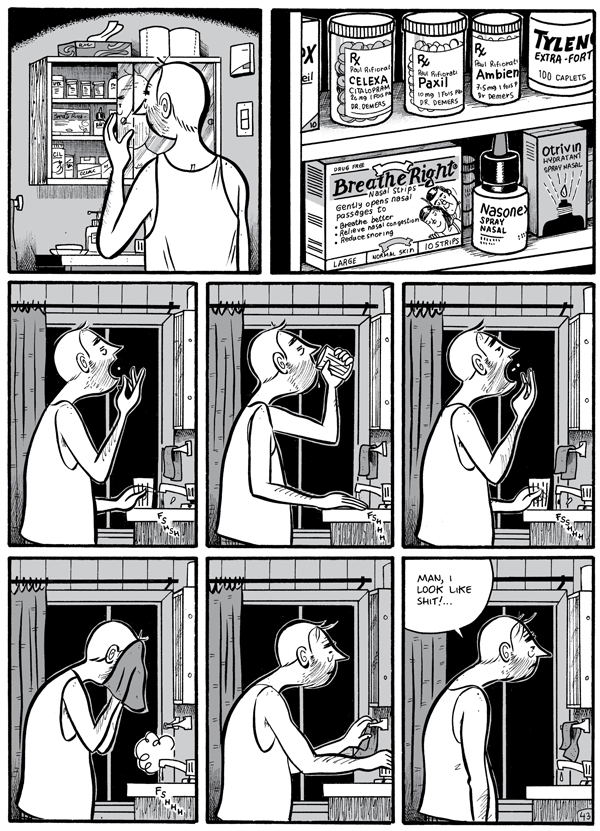

This is not a Paul that we have known previously. Not that Paul was a perfect person, but he typically tried to rise to the challenges life presented him, even if he was initially confused by them at first. But now he responds to most things with irritation, sometimes even anger. What gets him going can be boiled down to one word — change — and it comes up in literally everything, whether it’s a product, a habit, or the life trajectory of his daughter. Change means that he can’t grasp onto anything because everything is moving along while he struggles to stay afloat.

To a degree, this chapter of the Paul series feels meandering, almost directionless. Paul sulks around with nothing, in particular, driving him, nowhere to go, not much to do. He’s wandering, almost dazed, reliant on his memories of childhood and digging in his heels when it comes to change, whether it’s his daughter’s plans to move to England or the unavoidable existence of cell phones. If Paul seems lost, the book does, too.

But that’s no accident. This quality of Paul At Home reflects the reality of going somewhere without being able to see it as so many people experience it. Life can seem disjointed sometimes as you age and Paul, now in his 50s, no longer even has a partnership to cling to. He huddles in his apartment alone except for his dog, lacking anything that makes him feel like he belongs somewhere and with somebody. The book is looking for purpose because its main character is. And just as a superhero has a supervillain disrupting the order of the universe, the ordinary person has change doing the same, and it becomes more of a destructive force as aging continues.

As usual, the brilliance of Paul lies not in the exceptional quality of the life portrayed, but in the normality and therefore accessibility and familiarity. Rabagliati has a keen instinct when it comes to parsing out the key moments of human life that are common to most of us, regardless of what kind of life we are leading, and he understands the conflicts become deeper and the meaning of our responses richer as we grapple with them as older people because we’ve reached a horrible moment where the end might still be far away, but it’s definitely in sight now. That understanding of your own finality puts greater pressure on not solving all these problems necessarily but at least learning to manage them for your own happiness for the time you have left. If youth is about running away from this stuff, maturity is about accepting them and living contentedly regardless.

Paul At Home is partially about facing mortality and all that implies, but it’s also about taking stock of your life prior to the end and not letting what you haven’t accomplished overtake your understanding that there is still time left for you. It’s also a warning not to allow the most cherished parts of your old life to create a standard that feels unachievable in your present and jars you into inaction.

But Paul, like so many of us, is in the middle of his life, and he’s doing the best he can with it. That’s always been the case in the Paul books and what allows for little points of surprise, for happiness and sadness, and for regrets and moments of learning. In Paul At Home, Paul is stripped of so many things and brought down to his essence, and as many of us will find ourselves someday, in a position of finding his place in a world that seems less tangible as the years move on.