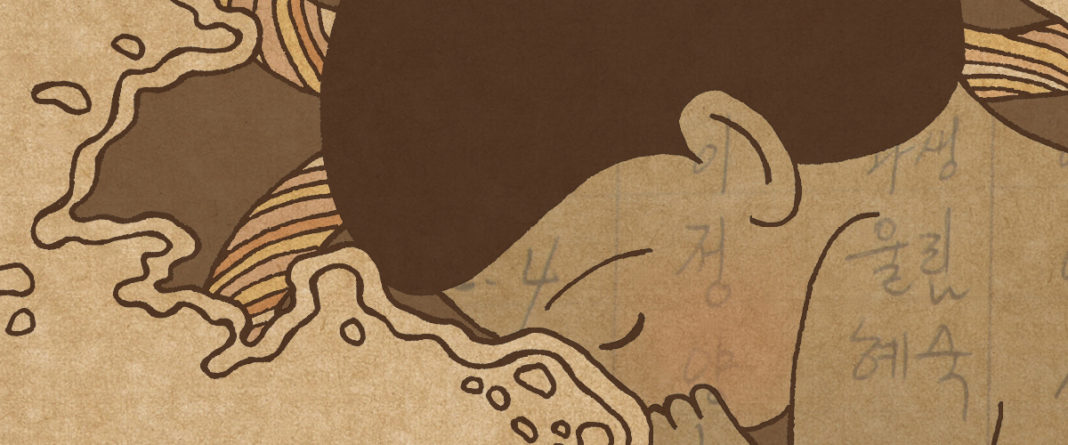

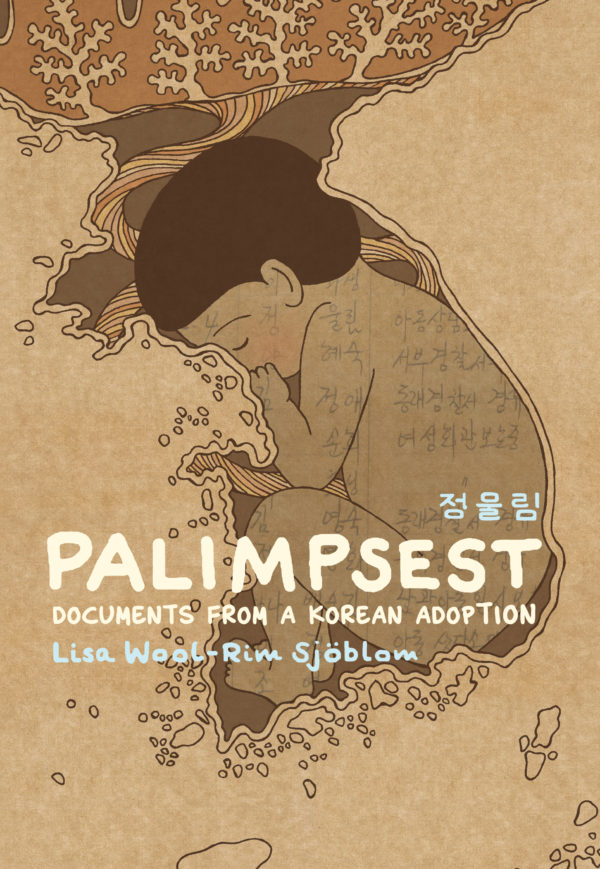

Palimpsest: Documents From a Korean Adoption

By Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom

Drawn and Quarterly

As the 21st Century progresses, multiple givens of life continue to be turned on their heads. The way society perceived certain circumstances are reversed often as the people most affected by them begin to speak up. One of those is most certainly adoption, particularly foreign adoption, in which children are taken from one country to another.

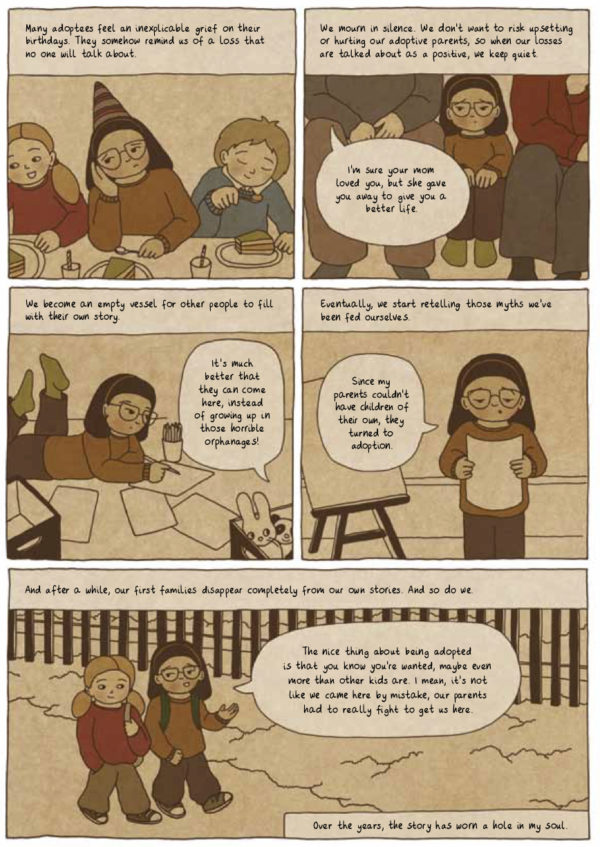

We’re taught to think that adoption is a noble choice for would-be parents to make, that there are children who need homes and families, and that we should be able to provide for the children who already live before we add more to the throng of humans using up resources. We’re taught to think that it’s a cut-and-dry transaction in which a child from a sad life without a family is given a new happy life with a family and that the complicated human psyches that we are so familiar with in other scenarios just breeze through this process into loving arms.

Guess what? It turns out that adoption is very complicated. Especially for the people who were adopted. It turns out that they are multi-faceted complex human beings who grapple with numerous emotions regarding rejection, displacement, alienation, and other psychological distress.

That’s the story that Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom tells in her memoir Palimpsest: Documents From a Korean Adoption. Alternately heart-wrenching, maddening, and thoroughly informative, Sjöblom opens up her life and her heart to an audience for an astounding record of what this new perception of adoption means in regard to the experience of real people walking in the world, building lives, and seeking answers.

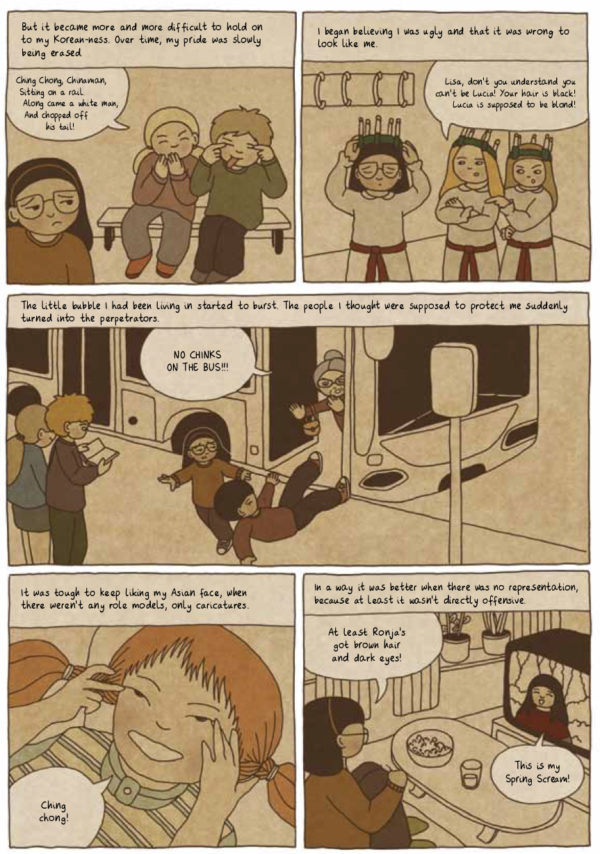

Sjöblom was adopted at the age of two from Korea, raised in Sweden and in constant struggle with a culture that she never felt she belonged in. Not that she was made to feel welcome. Sjöblom’s documentation of the casual prejudice she faced from Swedes is jarring and helpful in explaining what people from non-white cultures face in European countries and, of course, the United States. It’s hard to comprehend the piling-on of what I guess are considered micro-aggressions, a constant pricking of the skin that’s done enough with such consistency that real and permanent lesions form that keep so-called outsiders on the margins of white culture.

Part of Sjöblom’s reaction to this experience is to embrace her Korean heritage as best she can. It can be a stumbling effort for her sometimes, and often seems like an effort to stave off the demons that push her to self-destruction. That happens too, though, that’s the other part of Sjöblom’s reaction and I imagine it’s the same for many others in her position.

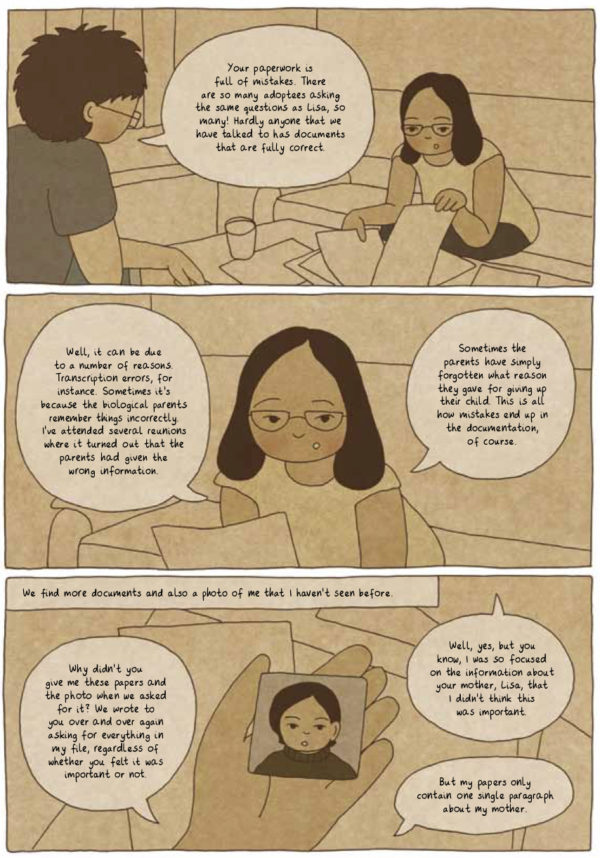

She survives that period of her life and as an adult with her own children more seriously seeks to find out about her past. That’s the point where the personal nightmare becomes an officious, bureaucratic one that at certain points resembles something out of Orwell or even Kafka. As Sjöblom and her husband begin to seek information from Korean adoption agencies, their life becomes an onslaught of clumsy misinformation and self-serving hedging on behalf of the bureaucrats that inhabit the world of international adoptions in Korea.

In Palimpsest Sjöblom documents clearly each infuriating step of her quest to find her birth-parents — every letter, every email, every phone call, every meeting. It adds up to a litany of unreliable narrators that she is forced to depend upon for the information she needs. But documents contradict each other, agency workers contradict documents and other agency workers, and lies become apparent and multiple — as if someone in Sjöblom’s position needs further distress in regard to her own biography.

The thorough and honest way that Sjöblom presents the material in Palimpsest is admirable just for the transparency, but the idea that she is doing so with her own life in order to represent the stories of others who will go untold, or at least unacknowledged by the wider world, adds a nobility to the effort that I don’t think she was thinking. But there is an anger and a despair that she is able to express whether ruminating on the implications of the unseen effects of adoption, the circumstance of her own journey outside of Korea, or the corruption and deceit that unfolds as she tries to solve the simple mystery of who she is.

Thankfully, Sjöblom is able to direct these feelings into something constructive both for herself and for others facing similar emotions and challenges, as well as those of us who just need to understand the realities of the adoptee experience in order to treat them with more dignity, compassion, and openness. Palimpsest is as much a detailed and convincing argument for change as it is a personal testament of self.