Memoirs of a Book Thief

Written by Alessandro Tota

Illustrated by Pierre Van Hove

Translated by Edward Gauvin

SelfMadeHero

I couldn’t help but think about the current interest in true crime stories as I read Memoirs of a Book Thief. Actually, the word interest makes it feel like a casual hobby when in fact our televisions — in both the streaming and broadcast areas — as well as a huge swathe of podcasting and that ever-reliable, enduring section of publishing are inundated with true crime stories. And these range from dramatic retellings to journalistic documentaries to amateur sleuthing.

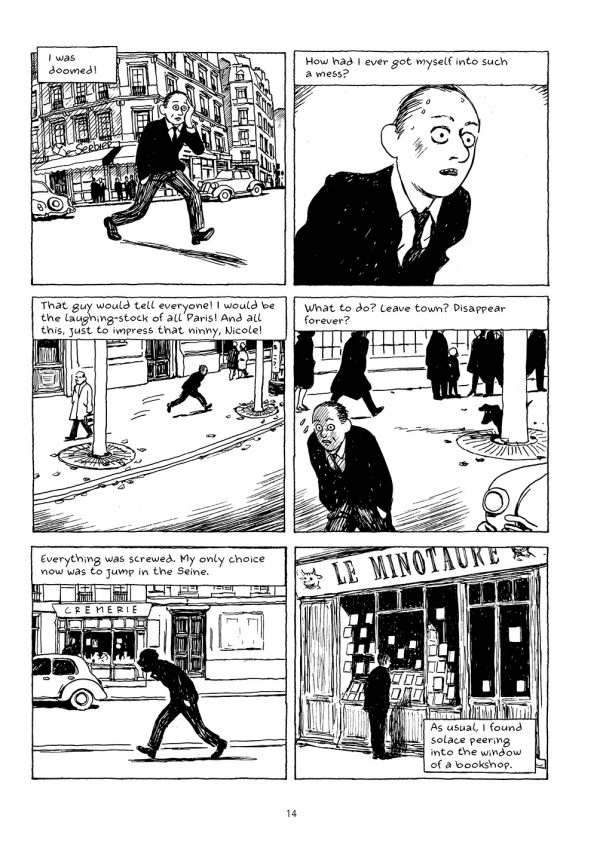

Memoirs of a Book Thief begins with a petty crime — Daniel Brodin commits his latest in a string of shoplifting efforts in bookstores in Paris in the 1950s — but the book doesn’t linger there. It instead moves onto other levels of violation, most notably plagiarism and falsification, in an effort to examine the allure of crime, especially as it relates to the creative worlds.

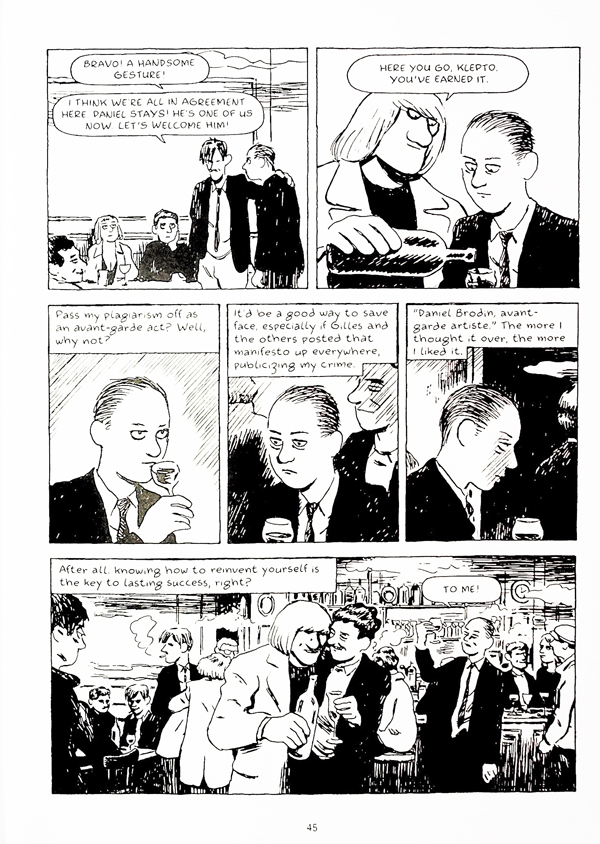

There are two notable moments for Daniel that change his life forever. In one, he crashes a poetry competition involving the elite literati of Paris and finds himself wowing the crowd with a deliberate appropriation of someone else’s work. In another, he becomes acquainted with Gilles and Linda, two so-called artists who take Daniel under their wings and introduce him to their gang of outsiders who strive to disrupt the mainstream and literary crowd by infiltrating their gatherings.

Gilles is a self-proclaimed criminal, an artist who moved onto petty crime during his travels and has translated his poor choices into a manifesto of sorts proclaiming criminal activity as a form of artistic pursuit and life as the only canvas that matters. The problem is that Daniel is a form of self-contained criminal that feeds on the genuine nature of Gilles and his revolutionary friends and tries to redirect what he gains from them into mainstream success, somehow conning both the misfits and elite to his advantage.

But Daniel finds out that it’s simply not enough to talk the talk. It’s a lesson people in arts and entertainment have had to learn over and over again, and it’s one that is forgotten each time. It’s led to a Sisyphusean situation where one person rolls the boulder up the hill, it tumbles back down, and then another person takes over, convinced that they know better the previous boulder-pusher. But it never works out.

Daniel’s story, though, unfolds in a landscape of provocation, post-war Paris when Sartre ruled the avant-garde and existentialism was its guiding principle. With a core of nihilism, an anything goes mad dash is created to distinguishing oneself from the rabble. A preoccupation with crime becomes the obvious affectation for someone who wants to seem dangerous or transgressive, like someone embracing the forbidden as acceptable in a meaningless universe. In this setting, his actions make perfect sense, but rather than seeking philosophical triumph by moving past his petty efforts, Daniel feeds off a real thug, Jean-Michel, as others in the crowd do, as if rubbing the scent off of a real criminal will transform a facade into the thing it’s pretending to be.

But Daniel proclaims at one point in the story that “a new generation is on its way” that will “take over and hasten the end of the old order.”

“I want to be a part of that at any cost,” Daniel says.

But that’s the problem with Daniel, that “any cost” part. He has no belief. He has no personal manifesto. There is no depth to him. This all makes him transgressive in a way that he doesn’t even begin to understand. Without any sense of right or wrong, he’s a psychopath that’s as ready to use anyone for his personal satiation. He has no real allegiances, no principles. He’s Trump, but much better read.

Which brings me back to all the true crime stuff, and also makes me think of the Morrissey song, “Last of the International Playboys,” in which the narrator says to British thugs the Kray Brothers, “In our lifetime those who kill / The news world hands them stardom / And these are the ways / On which I was raised.” We’ve come to acknowledge that crime and fame are linked to the point where we beg the media to not name or publicize the perpetrators of mass shootings anymore but to focus on the victims.

Meanwhile, serial killers become the focus of a million podcasts, their actions dissected like we would a Beatles song. Eventually, Dr. Hannibal Lecter becomes the main character in a TV series. We say we are fascinated by the transgressive nature of these people, by their rejection of what it means to be human, as a way of investigating exactly what it means that we are.

For all our fascination, and our justification of that fascination, we are not all psychopaths, we just want to understand them. And yet so many of us are blind to them when they appear in our life. If that were not so, Trump would not be president.

And so we, as a society, have all become that crowd of Paris existentialists, fascinated by the forbidden and embracing it as a way of making ourselves seem interesting and different. But in doing this, we’re vulnerable to our own book thieves that hover around us waiting to fulfill the destiny of a parasitic relationship that we don’t even realize exists.