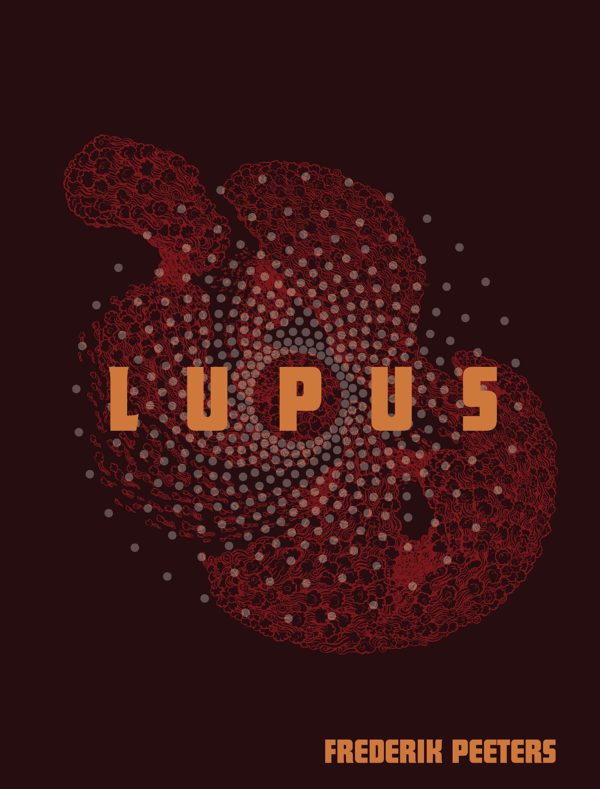

Lupus

By Frederik Peeters

Translated by Edward Gauvin

Top Shelf Productions

It’s hard to believe that is was nearly two decades ago that Swiss cartoonist Frederik Peeters made a splash with Blue Pills, a memoir about his HIV positive partner and her son, which had been released to high acclaim in Europe, but that’s probably because I didn’t read it until its 2008 English-language release. By that point, Peeters was already well-established in Europe, but for me at the time, Blue Pills set a tone for what I thought I could expect from his work. Peeters’ subsequent efforts were not quite what I foresaw, though, pursuing science fiction instead of memoir, often with a philosophical or symbolic aspect. But the qualities that were in Blue Pills — human, personal, emotional — weren’t totally missing from his work, they were just absorbed into unexpected trappings in projects like his Aama series.

Though it’s never been released in English before, Lupus is actually Peeters’ first work after Blue Pills. Originally published in three parts, Lupus makes a lot of sense as a gateway between Blue Pills and the other work of his that I read and enjoyed, but never witnessed any transition for. Lupus helps it all make sense and in doing so, puts Peeters at the top of my list as one of the world’s great graphic novelists.

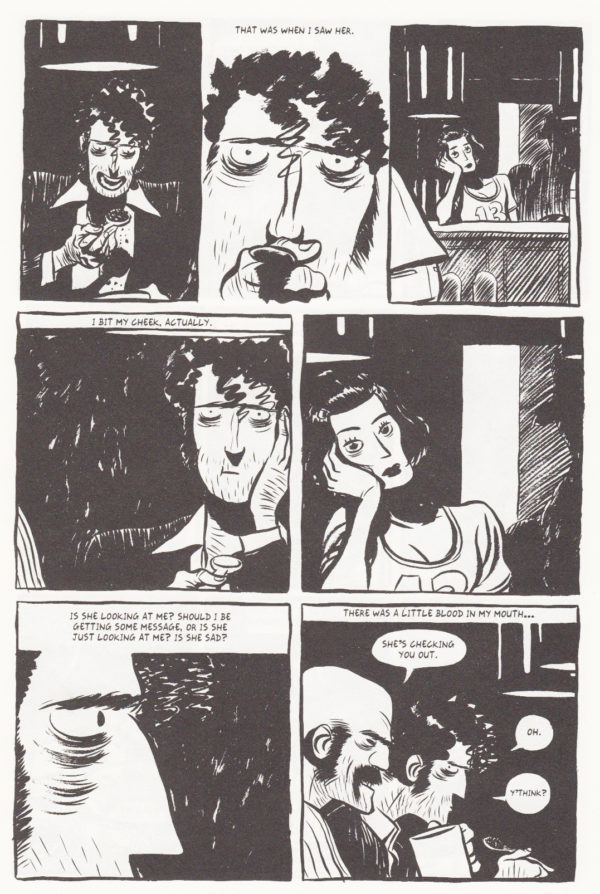

Lupus is a constantly shifting story, with the titular character on an aimless, drug-fueled intergalactic tour looking for unusual fishing spots and remaining intoxicated as consistently as possible. His travel partner, childhood friend Tony, seems like more of a loose cannon than the cautious Lupus, more coarse in his presentation and dismissive of seriousness. It’s their encounter with Sanaa, a young woman on the run from something, that changes the tone of the trip, and Peeters spends the book allowing the consequences of that meeting to unravel far beyond the intimate situation of its beginning.

As the settings change and the characters spiral in and out of the Lupus’ orbit, we see that there are two threads running throughout the story — the constant need to survive the situation the characters are in and the frequent fight for space in Lupus’ mind that the current situation has with aspects of the past that haunt Lupus. If he doesn’t always seem present in the moment, Lupus is able to rise to the occasion when most needed and what unfolds is the process by which he learns to put himself in the here and now in better, more productive ways — at least, hopefully, that’s how it will all end up.

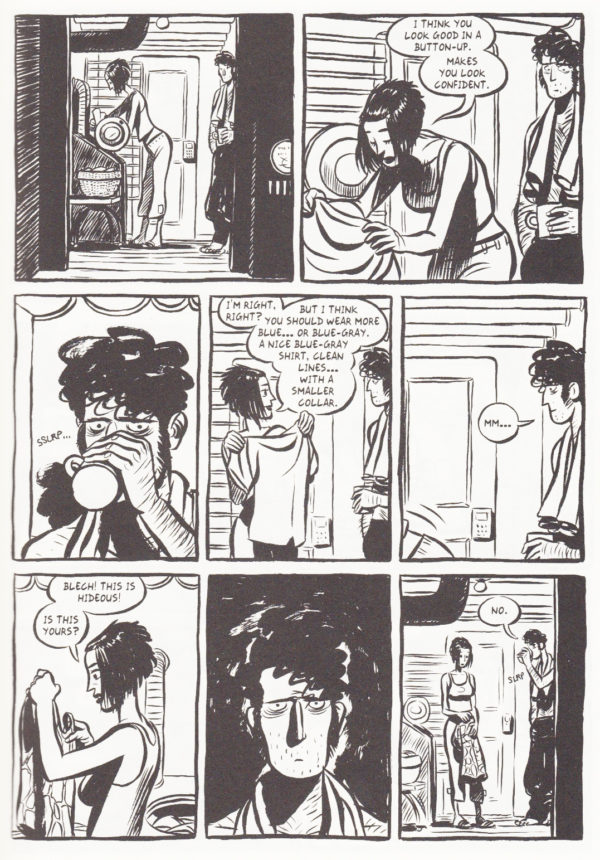

Peeters populates the story with characters who don’t express what they want to or should, and instead build relationships through hints and flirts and exasperated moments where they can’t quite bring themselves to go into any more detail about their situation than they already have. This is in contrast to a well-realized system around them that sends obstructions to focusing their concerns and meeting half-way by providing others with some reasonable understanding of each other. It also gives what is, in essence, a nuanced study of relationships a rollicking quality that allows the subtleties to trickle out in the midst of a space chase.

Peeters’ smudgy, personable black and white artwork gives the story a down-to-earth feeling that helps with the emotional familiarity that is crucial to its success. It gives personality to the characters, but he also harnesses it to expand on itself with more complexity in some sections, providing complex portraits of the locations visited as well as more abstract sections of vegetative movements through space mirroring those of Lupus, like memories made tangible and remaining on his heels.

Peeters has consistently shown that he has a great vision for the contemplative and intellectual aspects of storytelling that science fiction offers, in contrast to the action-oriented products that dominate the genre in our popular culture. With Lupus, it’s a revelation to find out that his approach was always fully-realized, with a stronger starting point than most.