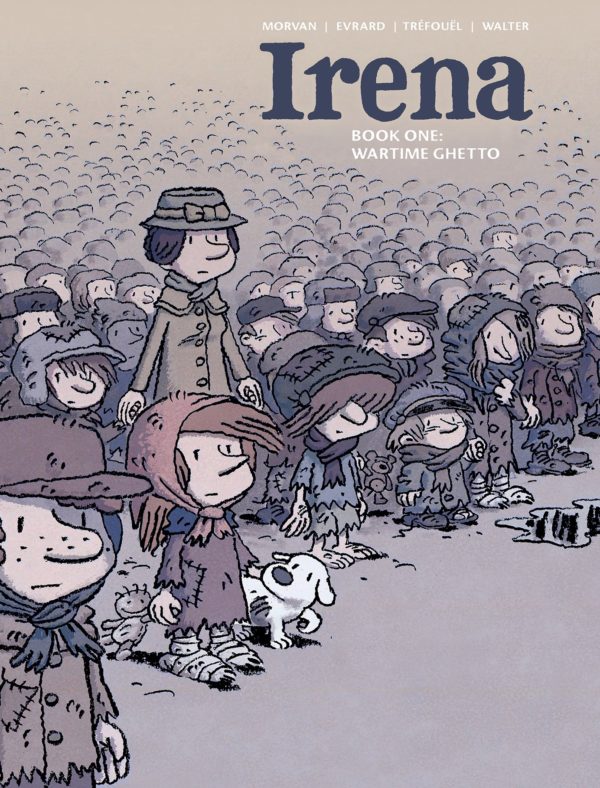

Irena Book One: Wartime Ghetto

Written by Jean-David Morvan and Séverine Tréfouël

Illustrated by David Evrard

Colored by Walter

Lion Forge

[Disclaimer: Lion Forge is a sister company of Syndicated Comics, which publishes The Beat.]

The first in a several volume French series dramatizing the life of Polish social worker Irena Sendlerowa, Irena Book One: Wartime Ghetto covers her years in the early 1940s giving aid to the Jewish population kept in the Warsaw Ghetto, which included a massive effort to smuggle children out and hide them from the Nazis.

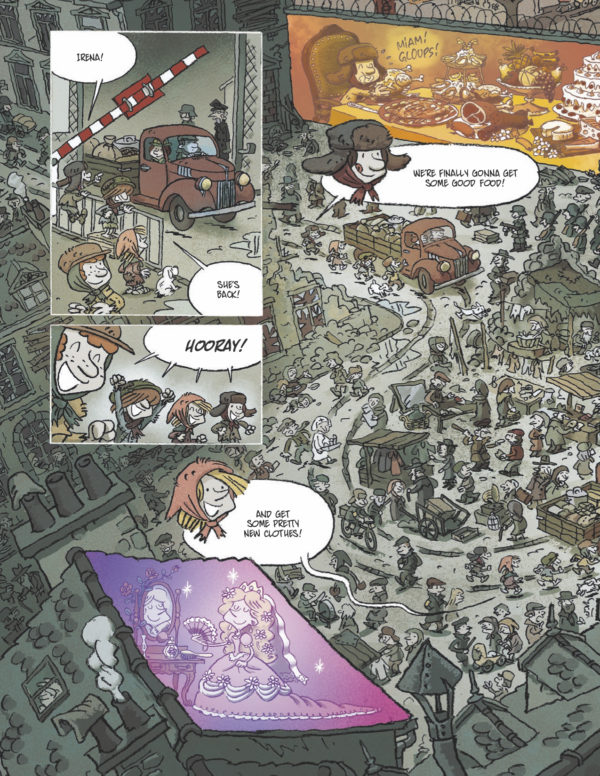

As the story opens, Irena is already established in the Ghetto and facing a cross Nazi guard reprimanding her upon trying to enter. But she does, much to the glee of the people there, bringing in supplies that they need to survive and being lauded as a folk hero and savior, larger than life. Evrard renders the scene in the Ghetto like something out of Where’s Waldo, with Irena somewhere in there, visually capturing the way she looked at herself and her mission — she was no better than anyone else, just one member of humanity doing her part.

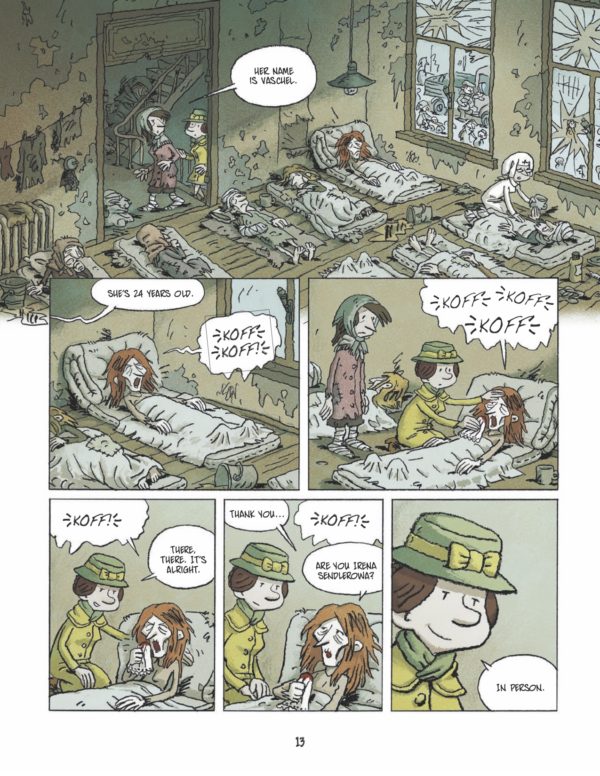

Joy gives way to reality, though, and the Ghetto is obviously a scene of poverty and desperation that Irena journeys further into, until she is called to the death bed of a decrepit mother who makes her promise to smuggle him out of the area to safety. This sets into motion her wider efforts to help the children there, but also forces her to face the true responsibilities of the role she has taken on, and accept the dangers inherent to that decision.

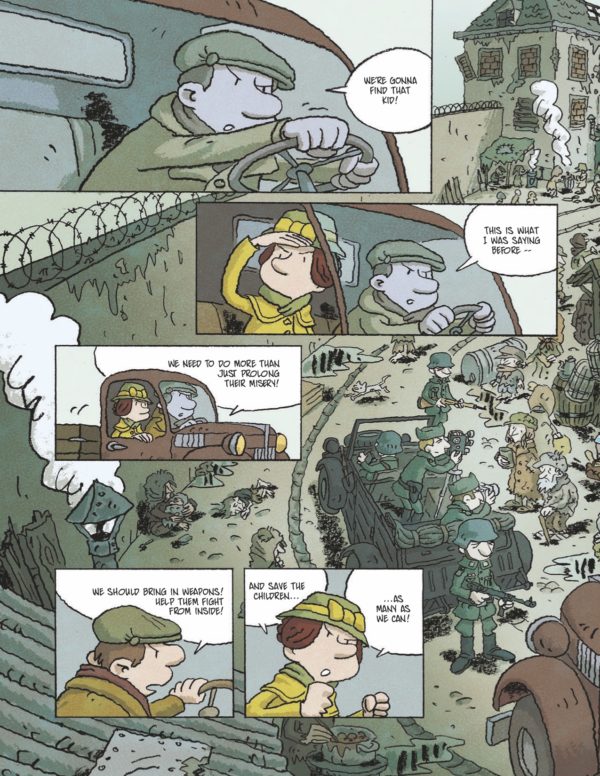

The book does not turn away from the horrors of the Ghetto, nor the seriousness of Irena’s work, these are constant specters in what unfolds, but it also acknowledges that what Irena did was exciting. The risk itself has an alluring aspect of adventure, filled with immediacy and possible jeopardy, even as it depicts the desperate measures employed to get the job done, including the intoxication of children to keep them silent and smuggling babies in enclosed spaces like tool boxes.

This is all dark territory, but the book rightfully acknowledges that these are multifaceted experiences for the people going through them and to bring them to life for young readers 70 years later, the usual formula of dry exposition and highly-passionate moralizing that is typically utilized with books of this subject matter can be obstructive to effective, pure storytelling.

Morvan and Tréfouël’s subject, Irena, controls the tone of the narrative thanks to her depiction as a solid and determined person providing a strong moral center for the action. But they never elevate her to superhuman, and that lets them present the tension of her missions in an edge-of-your-seat way that is appropriate to the subject matter, but also helpful in learning more about Irena herself and the number of people who helped her — many of them singled out in the book. This is not a book meant to lionize one person, but dramatize a vast, complicated effort to be human at a time when humanity was under seige.

Crucial to this depiction, though is Evrard’s artwork, which some might consider antithetical to the dark subject matter, but I think helps add intrigue and electricity to the story. His style is cartoonish, with aspects of it bordering on caricature, and traditionally the type of work that would be considered more appropriate for an Asterisk comic or, as I mentioned earlier, Where’s Waldo. But Evrard’s depictions of a Nazi-controlled Warsaw are intricate, sprawling, and hellish, and having figures functioning it that bring your mind back to something like Asterisk is highly effective in announcing its intent. I haven’t seen any evidence of Evrard having done previous work, but what he contributes here deserves attention.

This is a work meant to entertain kids even as it informs. It’s meant to directly connect with their emotions in terms they understand, rather than lecture about the darks turns of history that they need to learn. And it does this to offer up the idea of hope in the face of darkness — certainly a worthy and needed cause in in this day and age — and propose the idea that one person cannot expel the darkness, but they can create a small amount of light for those who desperately need it. It’s one thing to present the work of Irena Sendlerowa, but it’s quite another to do it in exactly the way she deserves, with vibrancy, and that’s what has been achieved here.

Comments are closed.