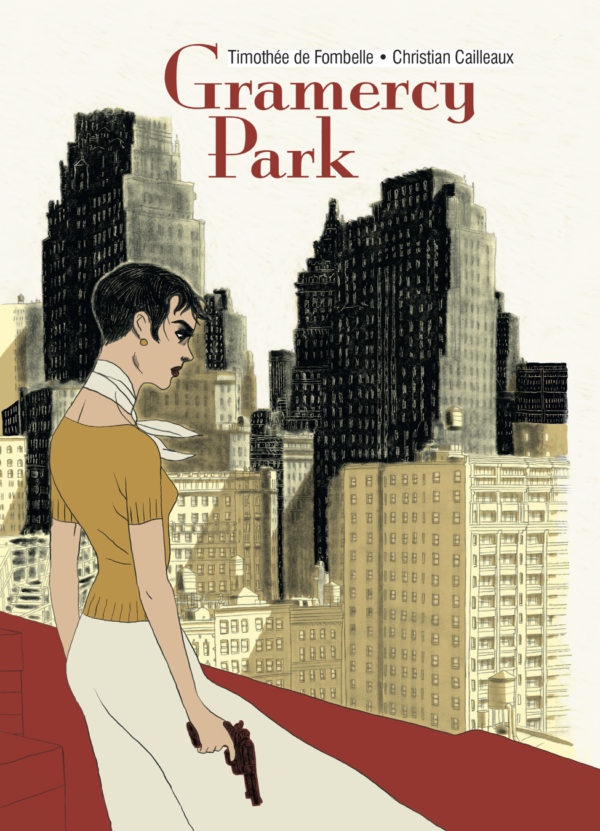

Gramercy Park

Written by Timothée de Fombelle

Illustrated by Christian Cailleaux

Translated by Edward Gauvin

IDW EuroComics

Why is the woman on the roof obsessively watching the window of a crime boss? That’s the central question of the Angoulême-nominated Gramercy Park and a pretty literal one that can lead to deeper levels of inquiry. High atop a building in New York City in the 1950s, a beautiful woman is keeping bees, but spends a lot of her time staring off the edge of the building straight into another one, and musing about the particulars of the life of the man she’s spying on. But the man sees her. Why does he let her surveil him?

The woman isn’t the only one watching the crime boss. There are also two cops, confined to their car, irritating each other, waiting for a lucky break to make an arrest. It never seems to come. It feels like an eternity in the car, a fruitless, frustrating one that only brings agitation.

The woman, though, isn’t wearing her reasons like a badge that she can pull out when questioned about it. She’s got secrets. Her name, we find out, is Madeleine, a former dancer in Paris. We find out about her life through flashbacks that tell us who she was and why she came to America. At some point in her story, we see her identify a body.

But the gangster, George Day, has his own problems. His accountant was supposed to prevent anyone from taking over the lease for the roof, but he’s allergic to bees. Mostly Day is irritated with his accountant and everything else. The only thing that really concerns him is Billie, the young girl who lives in his apartment. His daughter?

Between these players — Madeleine, the gangster, his men, the cops — the circumstances of the mystery unfold, using the conventions of crime noir to tell something more personal, more concerned with people. Transgressions of the law aren’t the most painful ones, Gramercy Park points out, and revenge is not all about blood and violence. Relationships can be the scenes of a crime just like dark alleys, and Gramercy traces the lines between people as motivations for painful transgressions in the name of getting what’s owed you.

What makes Gramercy Park exceptional is the way that de Fombelle takes the cliches of the noir genre and uses these surfaces as a step-ladder to depth. The personal dramas of the characters not only circle around the noir circumstances, but contain levels of their own that are insinuated in dialogue and explored in revelatory moments.

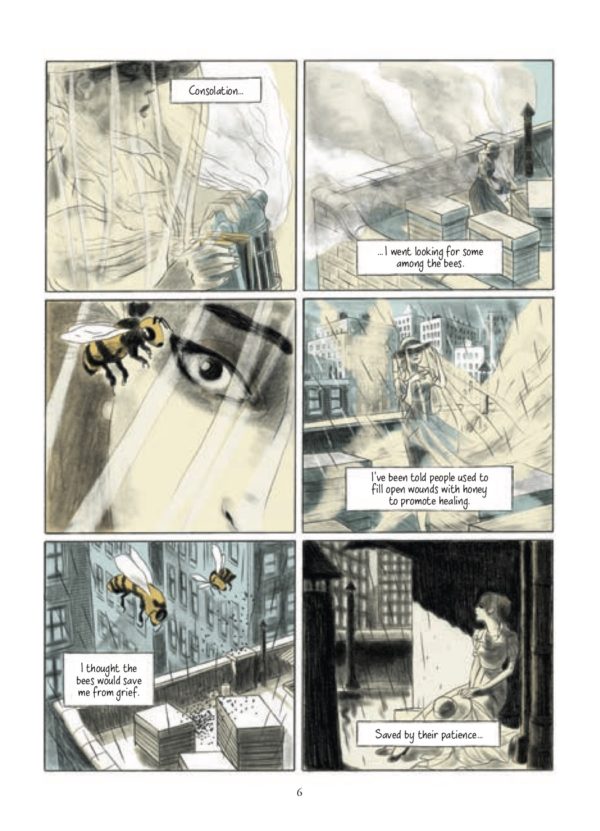

But the characters aren’t designed to be markers for either plot points or emotional themes. They’re well-realized, even down to the smallest players, and de Fombelle’s ear for dialogue makes them seem natural and real — the conversations are one of the highlights of the book and no doubt translator Edward Gauvin has a hand in them being so. But there’s also a haunted, almost dream-like aspect to the story that is brought forth especially by Cailleaux’s artwork, whether he’s rendering Madeleine perched on her rooftop, Day in his claustrophobic luxury apartment, or the magical and alive location of New York City, where surely each citizen seems to have a story just as vivid as this one.

If Gramercy Park is ultimately a story of revenge, it’s also one about loss and connection, about the need for other people, and the aspects of that need as selfish, and as a motivator for transgressions. In this way, it’s only appropriate that the crime noir genre is embraced for what is ultimately a story about how people’s selfishness affects the lives of others, and we always reach that moment when we realize that crime does not pay.