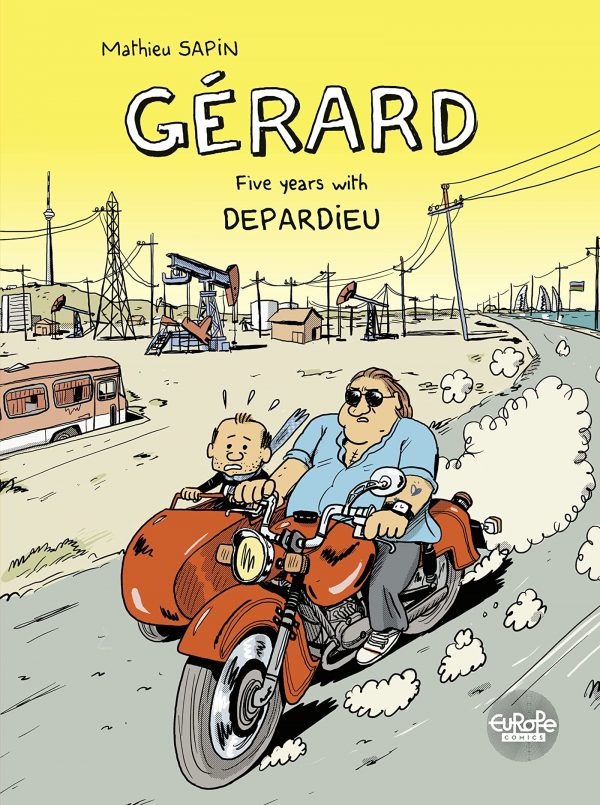

Gerard: Five Years with Depardieu

By Mathieu Sapin

Europe Comics

Is there an American equivalent for Gerard Depardieu? For sure there are men who equal him in his big mouth or body size or ego or unpredictability or charisma or his fame, but all of that rolled into one? Doubtful. And even then this person would need to be imbued with a certain Gerard-Depardieuness that you can’t even begin to qualify.

And the thing is, I don’t know if Americans really know what an equivalent for Depardieu would be since so few of really understand the deal with him. I mean, we know he’s an actor, we’ve seen a few of his films maybe, though I’m guessing the younger the American, the less likely that American has seen any of Depardieu’s films. Seeing his films probably wouldn’t help anyhow since Depardieu’s status is that of a cultural icon on the level of Serge Gainsbourg, who also fails to translate for most Americans.

So if you’re looking for some explanation of Depardieu’s magnetic hold on French culture and the influence he wields because of it, Mathieu Sapin’s Gerard: Five Years with Depardieu is not going to reveal much for you. However if you’re looking for a depiction of the chaotic, out-of-control, one-man-circus that is Depardieu’s existence and how that magnetic hold unfolds when people, and not just French people, meet him, Sapin piles it on until the point that you’re as exhausted as Sapin is.

The experience reminded me a lot of reading Shawn Levy’s excellent Jerry Lewis biography — the depiction of the subject is so vivid that you begin to feel like the subject is your roommate, and at a certain point, that means you want some space. This, if you are interested in the subject, is not a bad thing.

Sapin is a French cartoonist who gained access to Depardieu in 2012 when he was tapped for a television special accompanying the legendary actor on a trip to Azerbaijan. Sapin starts the memoir with a depiction of an encounter early in their relationship as he enters the Depardieu’s house to find him sitting around in his underwear amidst his valuable art collection talking excitedly on the phone about rotisserie chicken and Vladimir Putin, which he hangs up so he can go wash his “ass crack” and prepare for the press.

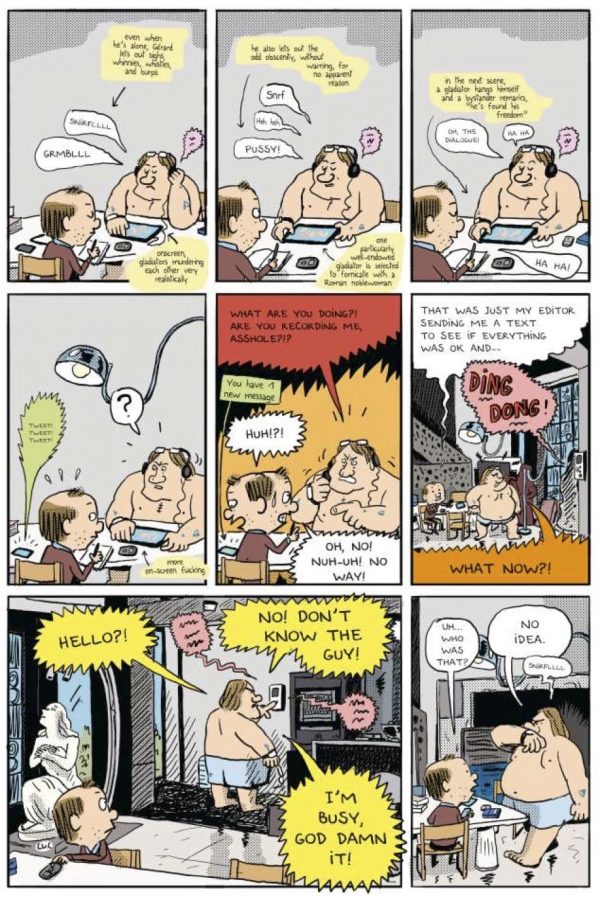

In some ways, that sums up the book, and yet it doesn’t do it justice. From the moment Sapin begins following Depardieu he is the audience to a non-stop monologue that darts back and forth, turns itself inside and out, grabs topics from seemingly no prompts and then returns to something from several twits-and-turns before that seemed like it had been retired from the stream of consciousness ramble.

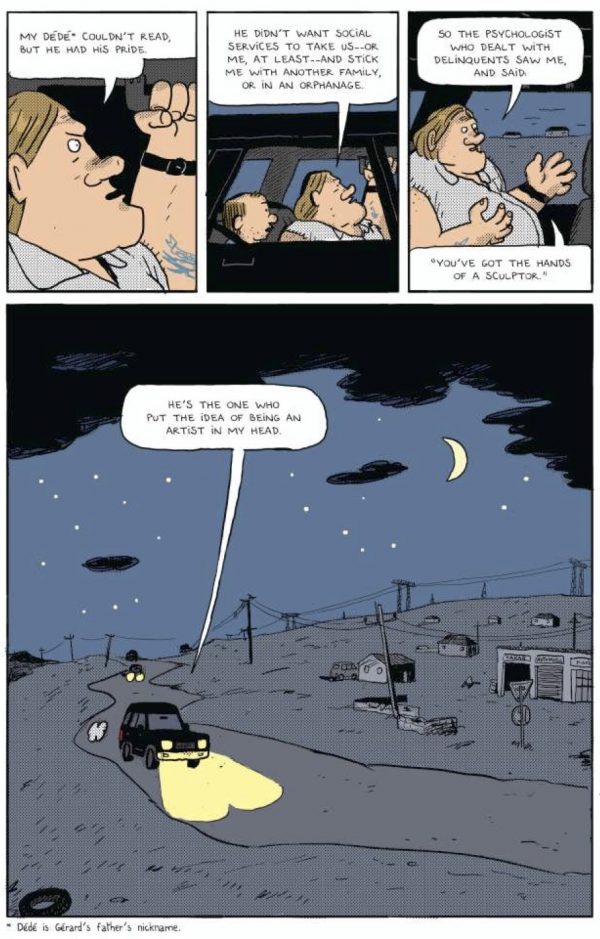

Depardieu might decide to talk about his own life — maybe his childhood, maybe his stardom — but then shifts into a philosophical skewering of the way he lives it, goes on a rampage about the tax situation in France, stumbles into some saucy story about an actress he’s worked with, transition to a meditation on death, wax poetic about some strange dish he was served somewhere, offer his analysis of art, toss out a few revelations about his personal interaction with Putin, and throws in a few comments about people around him.

As he does this, he’s barreling through whatever space he inhabits, drinking every alcohol insight and shoving copious amounts of food down his considerable gullet, while women of all ages, in all countries, beg for his autograph, a photo, anything.

There is too much Depardieu, that becomes obvious, and it can’t be contained in this one body, which has transformed into a hulking force of nature that reflects what lurks inside and despite the girth and age exhibits an unending energy to partake of every notion that crosses his mind. He is a force of nature — a force of French nature, one that doesn’t stop, but goes on and on and on, saying whatever comes to his mind, devouring what is in front of him, and going wherever he is led.

Sapin’s story unfolds without any promise of structure nor any possible way of providing it — actually, structure would be at odds with the subject of the book. In order to get context and background across, panels are littered with little sidenotes that explain all the background that might be lost in the kinetic insanity of what Depardieu is saying or doing and why he is saying and doing it.

It all ends up being a fascinating look inside the kind of fame that goes beyond what we typically see, the kind of fame that can only be equated with a figure like, say, Frank Sinatra, in that it combines the uniqueness of the personality, the strength of the personality, but also the fact that the personality is a remnant of a bygone age. But while the remnant might not command the spotlight of the popular culture in the same way as 40 years ago, he behaves as if he does and the world lets him.

The revelation is that despite the behavior, despite the excess, despite everything that precedes him, Depardieu actually seems, well … alright. An alright guy. Aspects of him might not fit into our current world comfortably, but he’s hardly a monster or even really a creep. He just seems like a guy to whom France handed everything possible and he accepted the gift and now he just goes with it. In the weirdest way possible, Depardieu comes off as being down to earth despite everything. Just himself. And that’s pretty much the best compliment of Sapin’s work I can think of.