Bix

By Scott Chantler

Gallery 13

Among the jazz musicians who have endured to be placed in that form of legendary status that transcends the community of jazz enthusiasts and bursts into the wider world, Bix Beiderbecke is not typically included. A cornetist who played in the 1920s, Beiderbecke is considered influential as a soloist and ahead of his time with his improv work, but his young death at 28 meant that a rapidly innovating form of music careened full speed from 1931 into the future with an onslaught of some of the most dynamically creative people ever seen in music. As the memory of Beiderbecke’s live performances slipped away, his legacy was reliant on recordings with the Paul Whiteman Orchestra and his own.

But enough people didn’t forget and Beiderbecke has gotten his due. One of those is Scott Chantler, whose recent take on Beiderbecke’s life, Bix, takes a different approach than most biography comics, certainly ones that cover musicians, and in doing so captures the spirit of experimentation that Beiderbecke included in his work.

Starting off in childhood, Chantler traces Beiderbecke’s journey from child prodigy to adult touring jazz musician. Beiderbecke was attracted to the music itself and also the freedom that music offered, and the allure of the lifestyle was a constant conflict throughout Beiderbecke’s life, preventing him from making valuable emotional connections that might have helped him through his frequently depressed emotional state. His physical reality of always being on the move, always traveling, alienated him from feelings of security and trust, and he filled the hole that created with alcohol. Throughout Bix Beiderbecke is seen casually armed with his flask, regardless of what the moment holds, and it’s the one constant presence in a life of quick change.

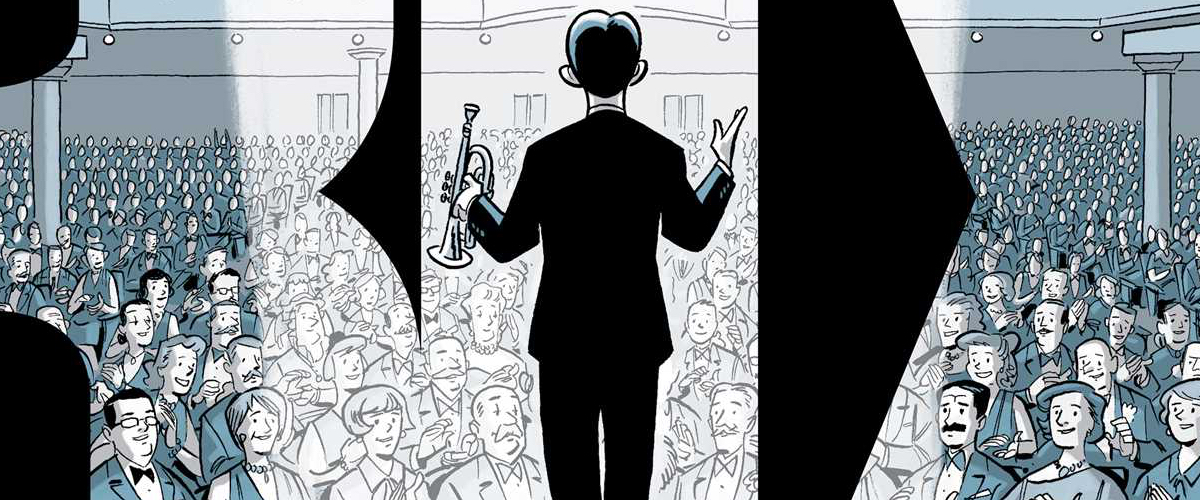

Chantler’s unusual choice is to present Beiderbecke’s life mostly in silence. As a pantomime presentation, this gives Chantler’s artwork and particularly his use of panels a chance to evoke the rhythms of both the music Beiderbecke played and the life he lived, often using the panels to reflect one or the other or both.

The only time in Bix that Chantler chooses to have his characters say words is in an earlier segment documenting a romance of Beiderbecke’s that illustrates how distant he could be from emotional connection, with the siren of jazz calling him to take to the road and the night, all the while trying his best to do what everyone is supposed to do. Or at least it’s what he imagines everyone is supposed to do — settle down, find a spouse, have a kid, a job, pay the bills, be happy. He tries to do that, but both he and his girlfriend know it’s not for him, especially as much of the dialogue has to do with her asking about his family and him evading the topic. He doesn’t want to acknowledge family.

The wordlessness in the rest of Bix gives readers the opportunity to fill in their own blanks regarding the specifics of some of Beiderbecke’s emotional state, perhaps demanding an exercise in empathy rather than spelling it out. The compulsion to self-destruct even as one focuses on creating is a constant in human existence and it’s one that we still struggle to completely understand. Chantler’s Bix takes some chances with that delicate endeavor. Instead of explaining it to you, it guides you through the circumstances and asks you to do some figuring on your own. There may never be a succinct answer to the question of “Why?” but the exploration of the circumstances will always be crucial regardless and Bix is an excellent way of doing that.