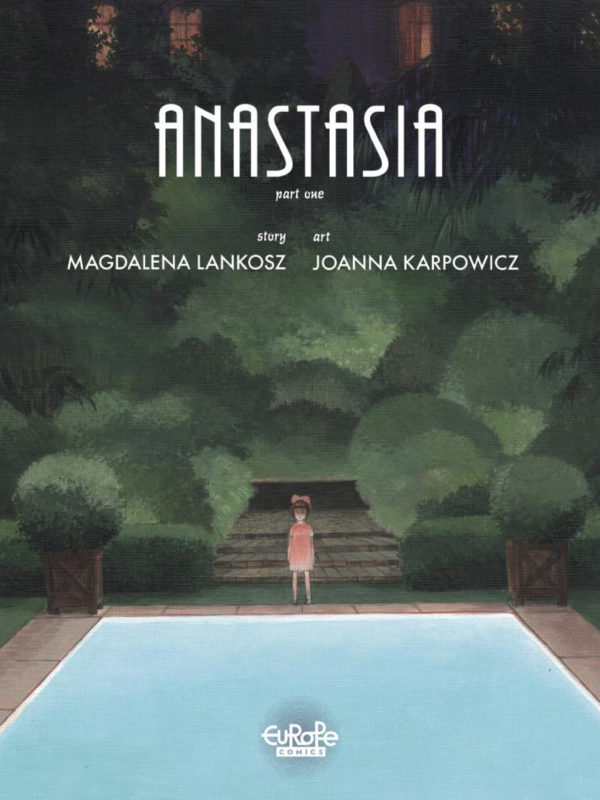

Anastasia, Part One

Written by Magdalena Lankosz

Illustrated by Joanna Karpowicz

Europe Comics

This seedy drama of old Hollywood borrows some circumstances from actual incidents and mixes them in with completely original depravity to concoct something that is less a throwback to the era it depicts and more an artsy evocation of trashy novels and exploitation cinema of the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s. In the hands of long-time Polish journalist, feminist author, film critic and maker Lankosz, it becomes a textural wallop of emotions.

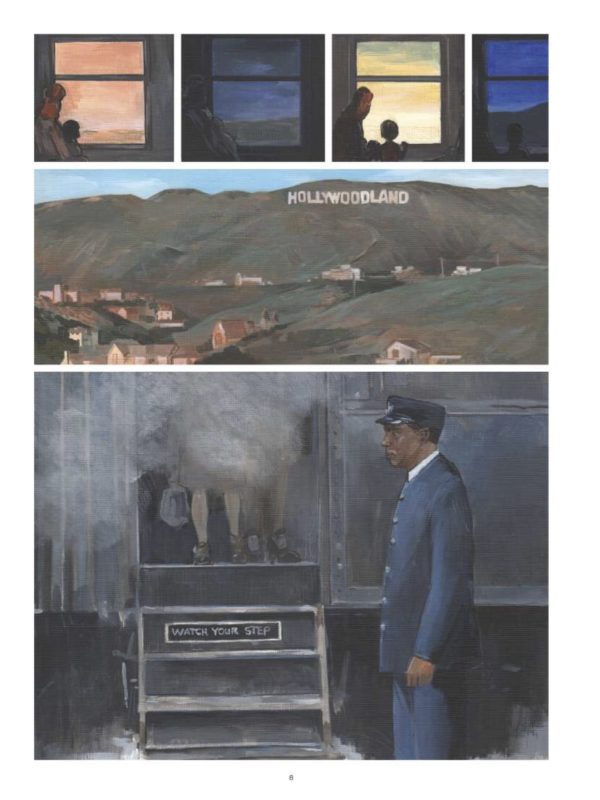

Anastasia is brought to Hollywood by her mother in 1926 and obviously not happy about it.

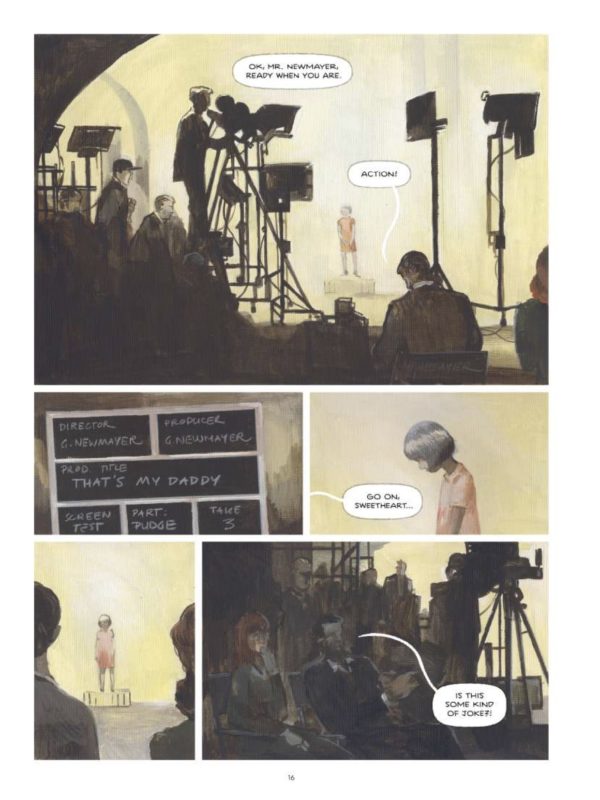

Her mother has one obvious purpose to the visit — make quick connections to turn Anastasia into a child star by pushing tall-tales about their Russian background at movie industry cocktail parties in order to charm producers into casting opportunities. But Anastasia isn’t rising to the occasion, and it’s with a mix of anger and coercion that the road to Hollywood success opens up to her.

But the old trope of celluloid dreams actually being nightmares covered in glitter comes at the mother and daughter full force, and as the sleaze overtakes the narrative, it’s with the purpose of examining the casual degradation of women within our entertainment system. It thrives on it and always has, and in Anastasia, it’s the currency by which the powerful men of Hollywood create triumphs and measure success, as well as the demon that diminishes self-esteem and causes the women to willingly descend into self-inflicted abusive nightmares.

There are ways in which this speaks to the idea of the American Dream itself. Hollywood is not the only glistening prize with a rotting core here — the promise of America as experienced by ordinary immigrants is also there. Anastasia’s mother escaped the terror of their homeland to face more darkness in an ordinary American life. Is it the Dream that’s a lie, or is this just the lot of women in the world? Is desperation to survive passed along from mother to daughter? And is Hollywood’s role one of a predator that lures desperate people, especially women, into a trap that finishes the job of the rest of the world?

The real star here is the art by Polish painter Karpowicz, who alternates elaborate depictions bursting with period detail with more sparse scenes that make it seem like Anastasia is wandering through various levels of Hell at times or held prisoner in some Lynchian holding pen. Her brushwork provides texture and emotion to the story, with an almost oppressive darkness that transforms a pulp melodrama into something resembling psychological horror.

If Sunset Boulevard is the gold standard for this type of story, Anastasia wraps in arthouse and exploitation elements that drive home the inherent melodrama and add a lurid quality to it, making it feel close to a David Lynch film (as Karpowicz’s Twin Peaks painting formalizes) not just in surrealist touches but philosophically as well, making jarring use of the very exploitation it criticizes to make the viewer (or reader in this case) question their own involvement with this process. It becomes a jarring and disturbing feminist statement.