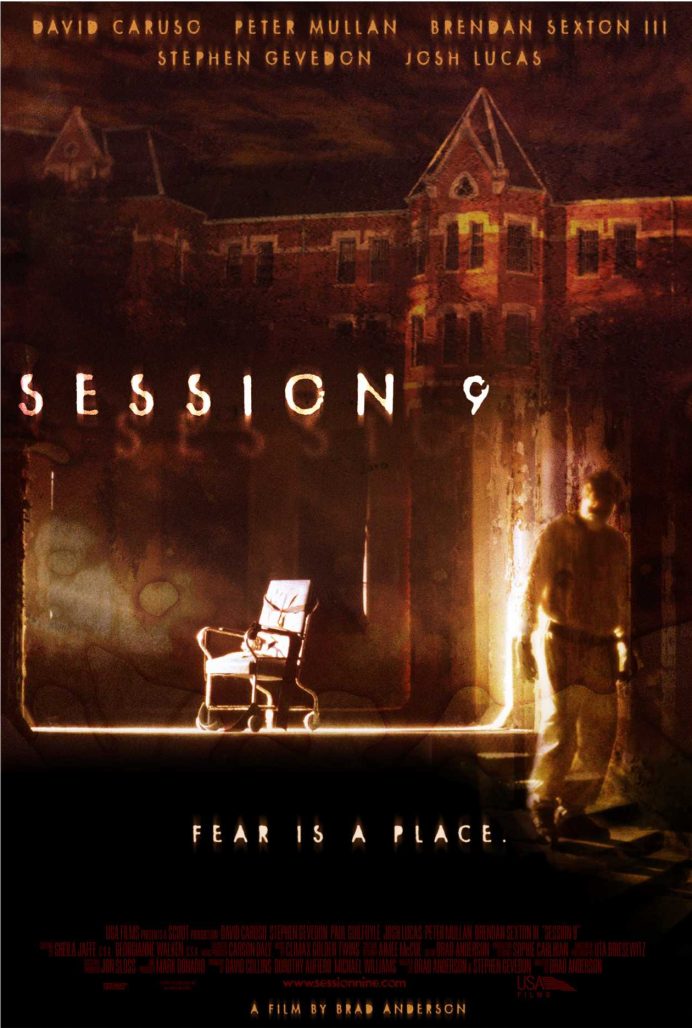

The only catch is that work is taking place at a decommissioned asylum. To get the pitch they’re going to have to promise wholly unreasonable things. The work involves removing asbestos (which can quite literally kill them), and, once again, the work is taking place at a decommissioned asylum, which seems to go forever and hold all kinds of super horrifying secrets in its dark bowels.

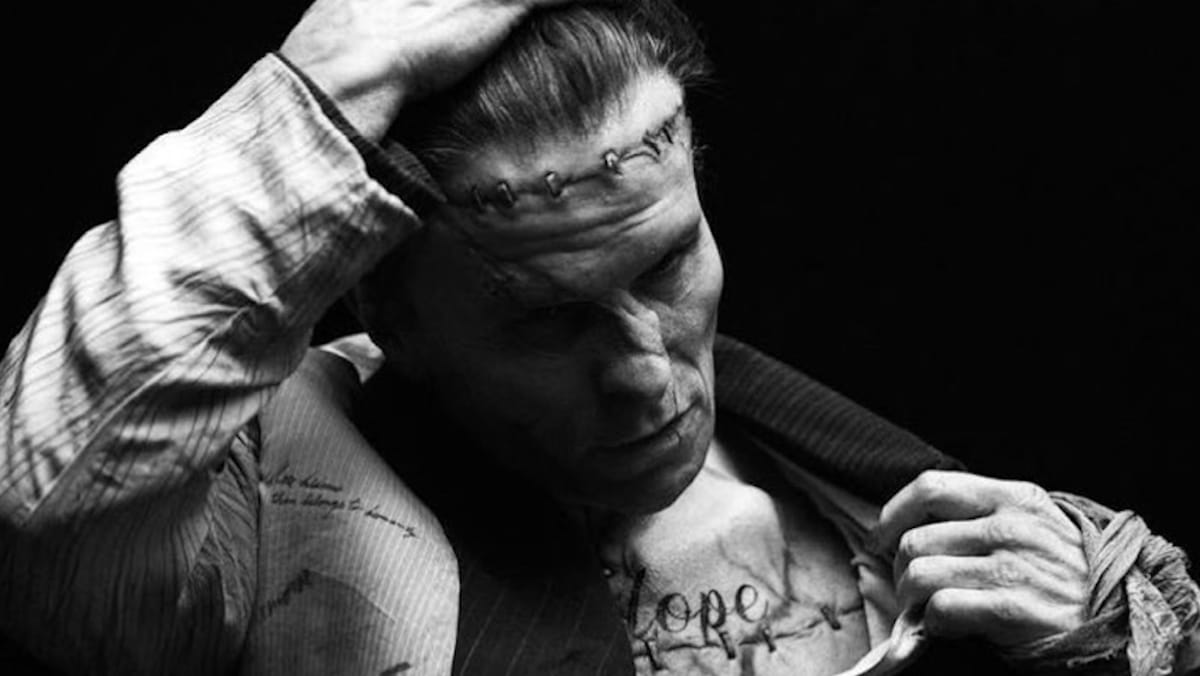

In a different sort of movie, there might be a monster or a spirit or a devil or something lurking. And, in Session 9, there very well maybe — ambiguity is part of what’s for sale. But even with that possibility in the dusty, potentially-toxic air, the real monster is something scarier, something we can every one of us relate to.

Yes, Session 9 is an understated, lo-fi ambush of a movie, one that uses the aforementioned defunct asylum setting in combination with chilling audio to deliver a scary psychological study of the human toll exacted by a certain type of work.

And that’s the real monster lurking in this film — work, the sacrifices we make to get it, and the pound of flesh it can exact from all of us.

This idea, however, isn’t really overt. It’s possible to watch Session 9 and come away far more afraid of its traditional horror elements. The set of this movie is fantastic, drawing inspiration from a real trend in the ’80s that saw state hospitals decommissioned, as well as the problems with asbestos faced throughout the ’90s and ’00s, as the material had to be removed once it become clear it was causing sickness and cancer.

If that weren’t enough, this movie’s sound work is incredible. There’s a slow reveal involving one character who speaks in several different voices, as well as a parade of hazy flashbacks from the main character that reveal more with audio than with the visuals. If you think violent noises and creepy voice acting are as scary as it gets, this move is going to absolutely wreck you.

But deeper than that to me was the steady theme that work — even if it seems peaceful and entirely above board — has the potential to destroy us all. Near the start of the film, main character Gordon has to promise that his crew can remove all the asylum’s asbestos on an impossible timeline — otherwise his business is going to die. Complicating this is the fact that Gordon has a new baby at home, the demands of which are trying. So, he ends up sleep-deprived and distracted while trying to remove an asylum’s-worth of asbestos on a schedule that no one in the movie thinks is possible.

On top of that, asbestos removal itself is pretty horrifying. As one of the character’s points out, if you’re not careful with your protective suit or mask, even a little bit of it can ruin your body and kill you. This is all really subtle and well-executed, but where it comes out most directly is when one of the side characters — a man on Gordon’s crew — gives a speech about having an exit strategy from the work. I think we’ve all given (or at least considered) that speech while at work, a fantasy about stopping it, about moving on, about being able to do literally anything else.

What I liked most about the movie though was that it really resists any impulse to preach, or if not to preach, than to paint working as wholly awful or always destructive. The movie gets across the point that work doesn’t have to be bad, that there are ways to work to live (or the characters have figured some out, even if they haven’t gotten to them), rather than to live to work. But that if we’re not careful, it can slowly sneak up on us, ambushing us from the dark corners of old empty buildings, so subtly we may not even realize it’s gotten us until it’s too late.