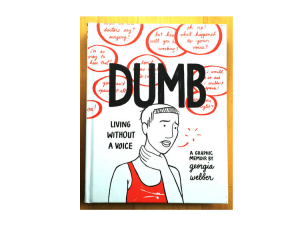

Georgia Webber’s graphic novel, Dumb, tells the story of how she copes with the everyday challenges that come with voicelessness. Webber’s book deftly demonstrates the use of graphic medicine (comics about health and the body) as a medium to communicate the physical, emotional, and financial experiences that accompany a health crisis.

Why is this important to comics creators? Because carpal tunnel syndrome isn’t the only health issue that can wreck an artist’s creative life and keep them from doing the work they love. Anyphysical or mental issue that keeps you from making comics is a “drawing” or “writing” injury, as far as I’m concerned. I hope you feel the same.

Here’s an interview with Georgia who came through New York City last November on her book tour and gave an inspirational presentation, which made me curious about her life as an artist coping with chronic health conditions.

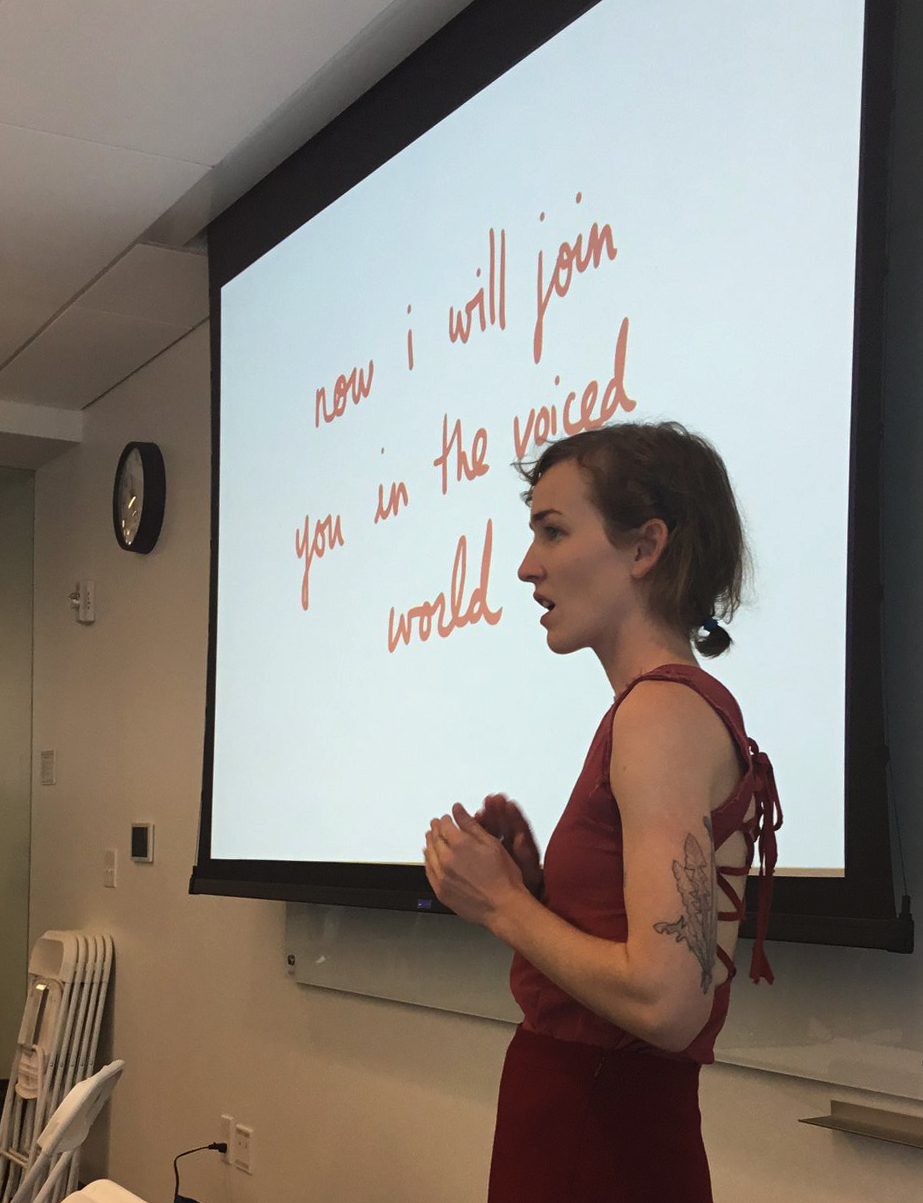

Kriota Willberg: When you were in New York City on November 5, 2018 at the McNally Jackson bookstore in Soho, you started your talk about Dumb by not talking! Your slideshow told us, in text and images, that when you are wearing red lipstick (which you were), it was a signal to the world that talking was painful and you would not be communicating vocally. You introduced yourself, explained the situation, and made some jokes to a live audience without spoken word. You stood before us, welcoming, confident, and vulnerable. We were sharing your experience of health and self care. It was a powerful introduction. What motivated it?

Georgia Webber: My understanding is that people instinctually trust their own experiences. Everything else is negotiable – the stories we hear, the facts we know, the ideals we strive for – but our experiences really stick. Believing this, my goal is to provide experiences as a way to communicate different experiences than people are used to having. Just talking about it isn’t enough. And talking is taxing for me, physically, so offering silence as an introduction was a natural fit. How often do we sit together so quietly?

Willberg: Why did you start making comics about your health experiences?

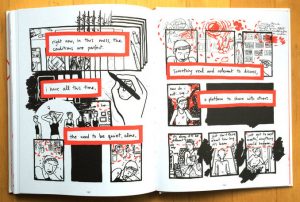

Webber: I always loved comics, respected the stories and their creators so much. It was paralyzing me (as a creator) because I was too afraid to let myself down with awkward writing or drawing and I thought I had nothing to say, anyway. I needed something that felt like mine to communicate so I could work through all that difficulty – and then my voice pain started and I had so much to say I could barely keep track of it all! It was a personal story that touched the universal, a subject that needed more awareness, and I hoped that writing about it might help the people around me to better understand what I was going through. I said to myself, “now or never.”

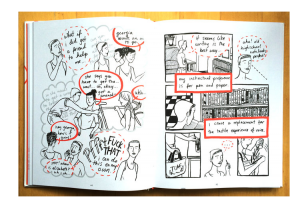

Willberg: Although voicelessness won’t keep you from holding a stylus and drawing, it can keep you from activities that support a creative practice. Can you describe some of the ways voicelessness impacted your life as an artist?

Webber: I gained and lost a lot of different supports through this experience: I lost the ability to talk through my feelings with friends but gained a lot of alone time to put my feelings on the page; I lost the structure and financial security of my job and gained a new understanding of the value of my work in the world. I lost trust in my sense of fairness, and my self-doubt was heightened to physically painful levels. When I couldn’t tell if my behavior, thoughts, or some other aspect of my unconscious were creating or worsening my pain, every moment felt unsafe, every decision or opinion in my head held the potential for harm. I’m still unraveling how deeply my body feels this lack of safety, and rebuilding trust in myself is a long, slow process. My creativity is so limited in the presence of fear! I’m working hard (and learning gentleness) to get my sense of self – and my creative forces – back.

Willberg: You have had other musculoskeletal conditions that have made drawing painful, since you made Dumb. Can you tell us about that? How are you coping now?

Webber: Well, this is partly why I speak of my beliefs and behaviors as a factor in my wellness. After pushing myself through the production of 80% of the book, Dumb, I was stopped in my tracks one day by hand pain. I had to leave my job early that day, but I never went back, because day by day I wasn’t finding any relief, and I recognized the pattern: this was just like my voice condition. I knew I would have to step away from everything all over again.

I didn’t want to make assumptions, so I went through all the diagnostic testing that one can, through the western medical system (thanking my luck that I was born in Canada, where I’m free to do the necessary tests without the burden of huge hospital bills). There was a whole lot of nothing, a few more doctors who didn’t take me seriously, or had very little patience for pain that isn’t easily explained.

So, I just went on my own way, selling my long-unused double bass so that I could pay for alternative therapies to discover what was happening under my skin, and deep in my psyche. I think I spent $5000 in four months! And I don’t regret a penny of it. I learned a lot. I also chose to study herbalism and cranial sacral therapy. I wanted to adapt to my new condition faster this time – since I still hadn’t recovered my voice, I knew that it could be years of welfare and struggle if I didn’t find a career that allowed for my work and my pain to coexist.

Willberg: Did some of the self-care lessons you learned coping with voicelessness help you care for your other injuries?

Webber: Definitely. Taking care of yourself is a skill, and so is healing yourself. You are the only person who is going to be there for every second of it, observing the shifts and effects that come with medication, diet change, physical activity, therapy, and mindfulness/self-love practices. The second time around I knew how hard it was going to be if I resisted or didn’t accept what was happening. It was easier to have the experience when I wasn’t upset that I was having it at all – whenever that acceptance is possible, which is a daily negotiation. I’m always feeling the push and pull of my wants and my needs, and I need to remind myself of that. It never stops, really.

Willberg: What change have you made that has had the biggest impact and most positive effect on your health or your state of mind?

Webber: The two things that really clarified my experience were meditation and learning about trauma. (Although small decisions also count, like every time I decided to get help for myself, whether it was calling on a friend, or seeing a new therapist, or sticking with my weekly appointments, or eating food that feels good for my body.)

Meditation was hard to stick with, but after about six weeks of my attending a weekly group, I felt such a shift in my capacity for emotional difficulty. I still sometimes forget the value of that practice, but whenever I stop the busy-making for long enough to actually meditate, or do yoga, I feel such relief! Learning about trauma taught me that my pain made sense, that I wasn’t broken. I read descriptions of common trauma behaviors and experiences, and it was the very first time that I saw myself reflected. Recognizing myself, learning that there were options for treatment and personal shifts, that changed my world.

Willberg: The ending of Dumb is… ambiguous (but visually striking). Why didn’t you end Dumb with an upbeat wrap-up?

Webber: Because that would be false – and boring. Ha! At the time that I wrote the end of the book, I was just recovering the use of my hands, and I knew I didn’t want to include anything about that. Dumb is about voice, not about all aspects of my life. I also wanted to break the narrative of “triumph over the body,” that the only way we’ll recognize people with health conditions is when they go above and beyond what we’d expect of them. We only want to see that they won.

The fact is that saying “people with health conditions” is synonymous with saying “people” – everyone has health, and everyone has health challenges. The assumptions we make about others, and what they may be up against in their experience of health, is a great divider. Many health conditions are invisible. Many health conditions are lived with, not a part of the past, but the present. I wanted the end of Dumb to convey that continuity, and show that it’s life, going on, learning and feeling and struggling, long after the book is done.

Willberg: What media and topics are you now exploring as a part of your creative practice?

Webber: In comics, I’m in the midst of writing a new book about trauma. I am hoping to provide information about trauma as a concept that readers can grasp, an experience that they can empathize with, and perhaps a guide to navigate it for themselves.

In the realm of voice, I’m working on bringing people together. I run a community organization called MAW Vocal Arts. A few times a year I host showcase-style events featuring solo artists, choirs, voice actors, storytellers, opera singers – anyone with a musical or non-musical voice practice is someone I want to celebrate. It’s a really amazing event, surprising me each time with how present and ready to participate our audiences are. I’m also working on my own voice performance, integrating silence into a voice practice that starts with body awareness and feeling. I’m hoping to share it with people who want to learn from my health experiences, in the form of workshops and performances. We’ll see what the year brings!